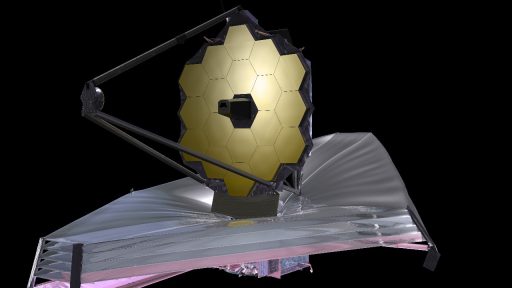

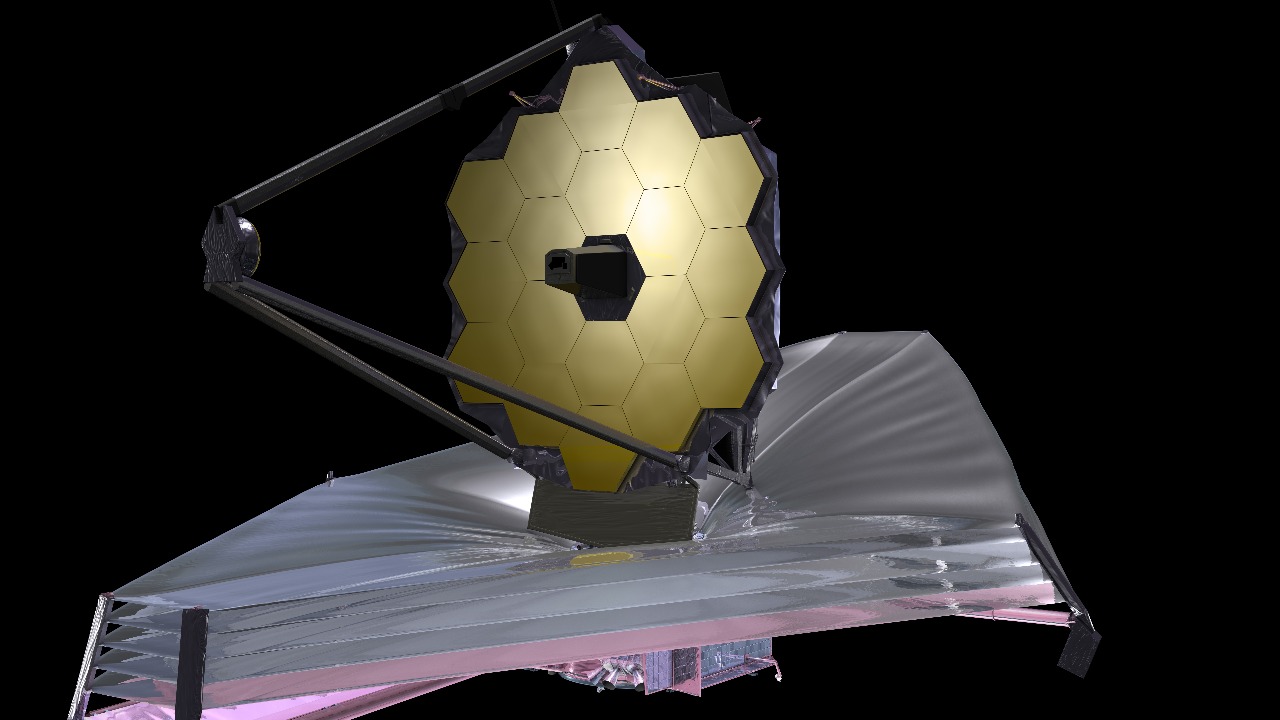

The James Webb Space Telescope is turning the early universe from an abstract idea into a place with specific addresses and surprising personalities. Instead of a cosmos filled only with tiny, primitive systems, astronomers are now seeing bright, mature galaxies and heavyweight black holes emerging far sooner after the Big Bang than standard models predicted. Those findings are forcing a rapid rethink of how quickly structure formed, how stars lit up the cosmic fog, and how invisible ingredients like dark matter shaped everything we see.

What is emerging is not a single dramatic discovery but a pattern. From record breaking galaxies such as MoM-z14 to mysterious “little red dots” and unexpectedly evolved galaxy clusters, Webb’s sharp infrared vision is revealing a universe that built complexity at breakneck speed. I see a field in mid-pivot, as long standing assumptions about the first few hundred million years give way to a more crowded, dynamic picture of cosmic dawn.

Galaxies that grew up too fast

Astronomers went into the Webb era expecting to find only small, embryonic systems in the first few hundred million years, yet the telescope is repeatedly turning up galaxies that look far more developed than theory anticipated. One team described the surprise bluntly, saying that “we expected only to find tiny, young, baby galaxies at this point in time, but we’ve discovered galaxies as mature as our own,” a reaction captured in early coverage of Webb’s deep fields that highlighted how quickly these objects must have assembled their stars and heavy elements linked to Jan. That tension between expectation and observation is now one of the central storylines in early universe research.

Detailed follow up work has sharpened the puzzle. In one survey, astronomers using the James Webb Space reported that some very young galaxies appear to age rapidly, likening the effect to “seeing 2-year-old children act like teenagers.” Their stars seem to form, evolve, and enrich their surroundings at a pace that strains conventional models of gas cooling and star formation. The implication is that either the first galaxies were far more efficient at turning gas into stars than expected, or key ingredients such as feedback from black holes and the role of dark matter halos need to be recalibrated for this early epoch.

MoM-z14 and the race to cosmic dawn

The most striking symbol of this new era is a bright system known as MoM-z14, which currently stands as the farthest confirmed galaxy ever detected. Astronomers identified MoM-z14 in a deep field and then used spectroscopy to lock in its extreme distance, placing it at a time when the universe was only a few hundred million years old, a result that has been showcased in images of the COSMOS field. The galaxy is not just a faint smudge at the edge of detectability, it is surprisingly luminous, which means it must host an intense burst of star formation or an early black hole, or both.

Reporting on MoM-z14 has emphasized how it pushes the limits of the observable universe and exposes gaps in current theory. Analyses of this object, described in detail by astronomers who note that the farthest galaxy ever detected is now a named, well studied system, show that its brightness and inferred mass are difficult to reconcile with gradual, bottom up growth scenarios, a point underscored in coverage of how JWST spots such distant galaxies. A separate analysis of MoM-z14’s light, highlighted in a discussion of how a bright galaxy called MoM-z14 revealed surprising phases after the Big Bang, shows that its spectrum carries signatures of rapid chemical enrichment, again pointing to a universe that wasted little time in building complexity after the initial expansion described in Anna Washenko.

Clearing the cosmic fog and assembling clusters

Beyond individual galaxies, Webb is now catching entire regions of space in the act of transforming from opaque to transparent. In one case, astronomers used spectroscopy to confirm a redshift of 13.0 for a galaxy seen just 330 million years after the Big Bang, and found that it appears to be carving out a bubble in the surrounding hydrogen fog. That observation suggests that some early galaxies were powerful engines of reionization, punching clear channels through the neutral gas that once filled space and allowing ultraviolet light to travel freely for the first time.

At the same time, a separate line of work is revealing that large scale structures such as galaxy clusters were already taking shape in this young universe. Using a combination of space based observatories, astronomers have identified a surprisingly mature cluster in the early cosmos, capturing what they describe as the cosmic moment when one of the largest structures in the universe started to assemble, a result detailed in a study led by a researcher at the Center for Astrophysics CfA. Follow up analysis of this same system, which was discussed again when the work appeared in the journal Nature, shows that its galaxies and hot gas already resemble those in much later clusters, indicating that gravity was able to pull matter together into massive structures far earlier than many simulations had forecast, a point reinforced in the Jan report.

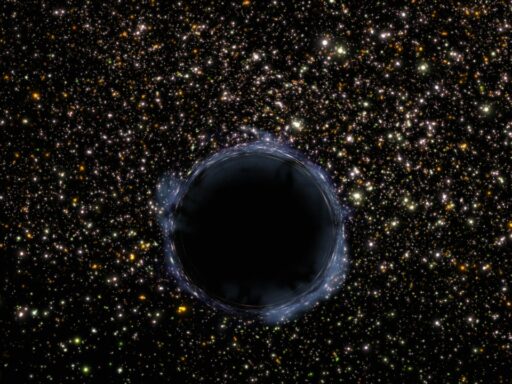

Little red dots and the rise of giant black holes

Perhaps the most dramatic shift in thinking concerns black holes. For years, theorists struggled to explain how supermassive black holes could reach millions or billions of solar masses so soon after the Big Bang, and Webb’s data are now forcing that question to the forefront. One analysis described the telescope’s impact as “a real revolution,” arguing that The James Webb is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe by revealing unexpectedly massive objects in very young galaxies, a theme explored in depth in a feature on how The James Webb is reshaping black hole science. These findings suggest that either black holes formed from unusually massive “seed” objects or that they grew through rapid, sustained feeding that current models struggle to reproduce.

Webb’s sharp eye has also turned up a population of compact, intensely red sources in the early universe that may hold clues to this growth. One study of these “little red dots” concluded that they are young supermassive black holes embedded in dense galaxies, offering a crucial piece in the puzzle of how central monsters like the one in the Milky Way came to be. Another team proposed that some of the mysterious red dots might be “black hole star” atmospheres, exotic objects in which a massive black hole is wrapped in a bloated envelope of gas, an idea presented as a welcome addition to current models of early structure formation and linked to signs that JWST has already found high mass black holes in the young cosmos. Together, these results point toward a universe where black holes and galaxies grew up together, each shaping the other from the very beginning.

Dark matter maps and the bigger picture

While luminous galaxies and black holes grab the headlines, Webb is also helping astronomers trace the invisible scaffolding of dark matter that underpins cosmic structure. New composite images created using data from NASA’s Webb telescope in 2026 and from the Hubble Space Telescope in 2007 show how dark matter and ordinary matter are distributed in the same region, revealing that the unseen component outweighs the visible one and strongly influences how galaxies cluster, a result described in a release that noted the images were Created using both observatories. A separate report invited readers to See dark matter mapped with James Webb Space Telescope images, explaining that this elusive substance passes through your body every second yet shapes the largest structures in the cosmos, a vivid reminder of how much of reality remains hidden even in the age of precision cosmology, as highlighted in the Dark coverage.