The race to build a permanent commercial foothold in orbit is no longer theoretical. Vast is now assembling Haven-1, a compact private space station that aims to be the first of its kind and is targeting a bold launch window in 2027. If the schedule holds, the single-module outpost could mark the moment low Earth orbit begins to shift from government-run laboratories to privately operated destinations.

Haven-1 is designed to fly as a standalone station, host professional astronauts and paying visitors, and test technologies that point toward larger habitats later in the decade. The project is still in development, but its move into hardware integration and a revised launch plan has turned an ambitious concept into a concrete near-term test of whether private industry can truly take over where the International Space Station will eventually leave off.

From concept to 2027 launch target

Haven-1 is described as a planned space station in low Earth orbit that is being developed by the American aerospace company Vast, with the goal of operating as the first commercial outpost over the course of its lifespan. The single-module station, known simply as Haven, is intended to function independently rather than as an add-on to an existing government complex, which sets it apart from earlier commercial efforts that focused on visiting the International Space Station. According to public technical descriptions, the habitat is sized to support a small crew and is meant to demonstrate how a private company can own and operate a destination in orbit around Earth, rather than just sell rides to someone else’s facility, a shift that would move commercial activity into a new phase of maturity for American spaceflight.

Vast has now advanced the project into a clean room integration campaign, where the primary structure is being outfitted with internal systems and prepared for acceptance inspection at its headquarters. Company materials describe Haven-1 as the world’s first commercial space station and invite customers to create their own mission profiles, signaling that the business model is built around selling dedicated stays and research time rather than simply leasing a seat or two on a government mission. The official program page notes that the Haven-1 hardware is undergoing detailed assembly and testing at Vast HQ, a step that typically precedes environmental qualification and final launch processing for a station of this scale, and it underscores that Haven is the company’s near-term product while larger stations are planned later in the decade.

Integration milestones and the slip to first-quarter 2027

The most concrete sign that Haven-1 is moving from PowerPoint to reality is its progression into a formal integration phase. Vast has reported that the second phase of integration will incorporate avionics, guidance, navigation and control systems, and air revitalization hardware into the already completed primary structure, with the company emphasizing that integration maturity increases as these subsystems are brought together. Earlier work focused on structural assembly and basic outfitting, and the current phase is where the station becomes a functioning spacecraft rather than just a pressure vessel, with teams validating interfaces, processes, and the performance of life support and control systems that will keep crews safe in orbit.

That technical progress has been accompanied by a schedule reset. Vast has delayed the Haven-1 launch from an earlier target and is now planning to fly no earlier than 2027, a shift that reflects the complexity of integrating thermal control, life support, and other critical systems into a first-of-a-kind vehicle. The company has framed the delay as a way to ensure that data from ground testing can be fully vetted before a crewed mission, with the expectation that, if partners agree with the results, they will put a fully trained crew on board Dragon and send them to the station. Public updates shared by spaceflight commentators indicate that Vast’s Haven station is now scheduled for launch in the first quarter of 2027, aligning the technical integration work with a specific window on the manifest rather than an open-ended future date.

Design, transport, and operations in low Earth orbit

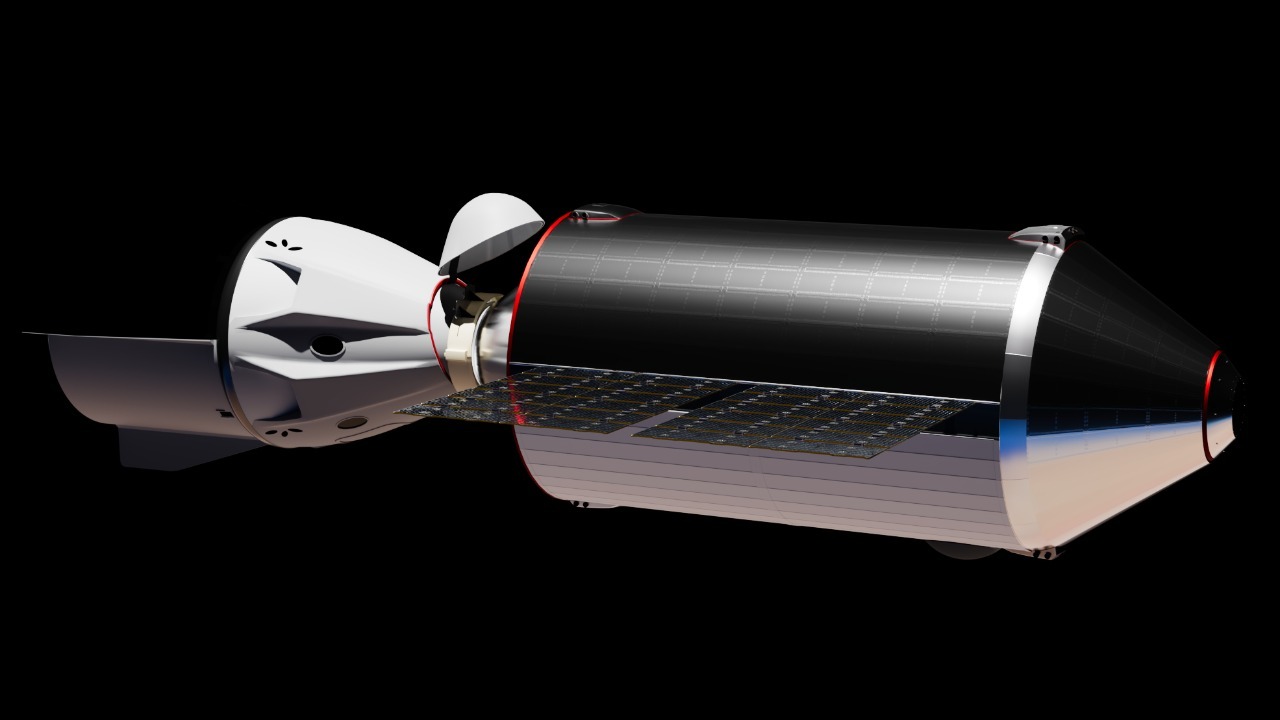

Haven-1 is intentionally modest in scale, a single-vessel station sized to fit within the payload fairing of a Falcon 9 rocket while still hosting up to four astronauts at a time. Vast’s near-term product strategy centers on this compact habitat, which can be launched in one piece and then operated as a standalone destination before the company attempts a larger, multi-module station later in the decade. The design is optimized for low Earth orbit operations, with systems tailored to the constraints of a small volume and a focus on rapid deployment, and it reflects a belief that a smaller, simpler station can reach orbit and begin generating revenue faster than a sprawling complex that tries to replace the International Space Station in one leap.

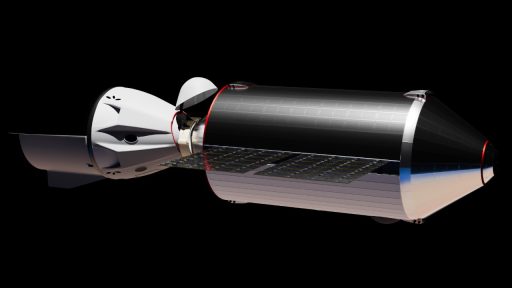

The transportation architecture leans heavily on existing commercial vehicles. The single-module station will launch on a Falcon 9 rocket and is expected to be visited by up to four Crew Dragon spacecraft on short-duration missions, creating a cadence of crewed flights that can support research, tourism, and technology demonstrations. Visuals and descriptions shared by Vast highlight Haven-1 as a single-module stand-alone destination in Earth orbit, with Crew Dragon vehicles ferrying the first astronauts to the station and docking for stays that resemble boutique expeditions rather than long-duration government rotations. This approach allows Vast to focus on the habitat and its internal systems while relying on proven launch and crew transport hardware from partners that already fly regularly.

Tourism, training, and the first “space hotel” pitch

Vast is not shy about positioning Haven-1 as both a research platform and a kind of orbital getaway, with marketing that leans into the idea of the first space hotel while still emphasizing serious science. Social media posts describe the station as a single-module stand-alone destination and highlight that Crew Dragon will ferry the first astronauts to the station, framing the experience as a curated stay in orbit rather than a purely utilitarian mission. That framing matters because it signals that the company expects a mix of professional astronauts and private visitors, including high-net-worth tourists and corporate clients who want to fly their own experiments or media projects in microgravity while circling Earth.

To make that vision credible, Vast has brought in experienced human spaceflight talent. Reporting on the program notes that a former astronaut has joined the company as Haven-1 moves into integration, with the role focused on helping the single-module station support up to four Crew Dragon visits and ensuring that operations are conducted with both speed and autonomy. Another detailed profile explains that Haven-1 is intended as a temporary facility, to be followed by a bigger, permanent station called Haven-2, and that astronaut Drew Feustel is training tourists and other private fliers for missions with companies such as Vast, Axiom, and Sierra. That combination of professional oversight and tailored training suggests that the first visitors to Haven will be prepared not just to enjoy the view but to contribute meaningfully to the work on board.

Artificial gravity research and the path beyond Haven-1

Beyond tourism and short-term missions, Haven-1 is also being positioned as a testbed for technologies that could reshape how humans live in space. Technical papers on partial gravity research opportunities describe how artificial gravity habitats will play a critical role in humanity’s long-term, sustained expansion into the solar system and beyond, with particular emphasis on Mars and lunar artificial gravity research. Haven-1’s design, which has been discussed in the context of experiments that attempt to mimic lunar gravity, fits into that agenda by offering a controlled environment where rotating systems or other mechanisms could be evaluated in orbit, providing data that cannot be gathered on Earth. If those experiments succeed, they would inform the design of larger stations and deep-space vehicles that need to protect crews from the health effects of prolonged weightlessness.