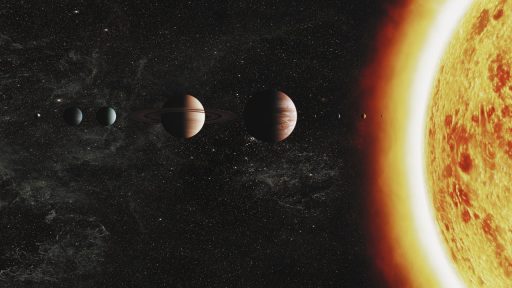

Long before the Sun actually dies, astronomers have already sketched a chilling map of what will happen to every world that orbits it. The picture that emerges is not a single explosion but a drawn out unravelling, from scorched inner planets to a ghostly shell of debris around a stellar corpse. That distant future will not touch anyone alive today, yet it reshapes how I see the fragile stability of our Solar System right now.

By tracing how stars like ours age, researchers can follow the chain of events from gentle warming to planetary engulfment and, finally, to a dark, thinned out system ruled by a white dwarf. The same physics that keeps the planets in their neat paths today also dictates how those orbits stretch, break and, in some cases, vanish entirely once the Sun runs out of fuel.

The Sun’s slow turn toward catastrophe

For the moment, the eight planets of the Solar System sit in orbits that are stable on human timescales, but that calm is temporary when viewed over Billions of years. As hydrogen in the core is exhausted, the Sun will brighten and swell, gradually turning the inner system into a hostile zone where oceans boil away and atmospheres are stripped. That transformation is not a sudden flip, it is a long, predictable evolution that astronomers can model with the same equations used to understand other aging stars.

Those models show that in roughly five billion years the Sun will enter its red giant phase, its outer layers ballooning outward while its core contracts and heats. At the same time it expands to become as large as 250 times its current size, the surface temperature of the Sun will decline, turning it into a bloated, cooler but vastly more destructive presence in the sky. On any map of the future Solar System, that swollen star dominates the inner few hundred million kilometres, erasing the familiar architecture we know today.

Earth’s place on the doomsday map

Long before the Sun physically reaches our orbit, rising heat will strip away the conditions that make Earth habitable. As the oceans evaporate, the planet will lose its water reservoir and, as one analysis starkly puts it, Without water on Earth, the tectonic plates will completely stop moving, shutting down the geological engine that recycles carbon and stabilises climate. That same work projects that in about 7.6 billion years, Earth and the moon will likely be engulfed as the red giant Sun grows to roughly the size of planet Earth’s current orbit.

Other studies reach a similar conclusion from a different angle, focusing on how the expanding star interacts with our atmosphere and orbit. In about five billion years, scientists say that the Sun will burn the last of its hydrogen fuel and begin to swell, and when this happens, it will expand and destroy Earth as tidal forces and drag pull our planet inward. Recent modelling by Earth specialists suggests Earth probably will not make it out intact, and But even if some remnant survived, its surface would be sterilised and reshaped beyond recognition by the Sun’s final convulsions.

Inner worlds swallowed, outer giants exiled

On the terrifying map astronomers now draw, Mercury and Venus are the first casualties, spiralling into the Sun as its atmosphere brushes their orbits and robs them of angular momentum. As the red giant phase peaks, the inner planets are engulfed in sequence until Earth and the moon are lost, leaving only scorched debris and gas feeding the star’s outer layers. Observations of other systems support this picture, with Astronomers catching a glimpse of this process in ZTF SLRN-2020, a star that swallowed a planet and briefly flared as it digested the incoming world.

Farther out, the story is less about engulfment and more about orbital upheaval. As the Sun sheds mass, its grip on the remaining planets weakens, and the surviving worlds drift outward into a colder, more tenuous environment. Detailed simulations of What will happen to the planets during the death of the Sun show Mars, the asteroid belt and the outer giants migrating to wider orbits as our luminary loses mass and eventually turns into a compact white dwarf. In that reshaped system, the familiar spacing of planetary paths is replaced by a more stretched out, fragile configuration that is vulnerable to later disturbances.

The fate of Jupiter, Saturn and the distant frontier

For the gas giants, the future is harsh but not necessarily fatal. One recent overview notes that Le Bourdais of explains, “We do expect the gas giants in our Solar System to survive the death of the Sun,” although they will likely end up in the outer region of their system. As the red giant Sun engulfs the inner planets, some of their material will likely get thrown deeper into the system, where it can rain down on Gas Giant Planets, briefly heating their upper atmospheres before they cool again to temperatures hundreds of degrees below freezing.

Beyond them, the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud form the system’s icy frontier, and their orbits are even more sensitive to changes in the Sun’s mass. As the star sheds its outer layers, comets and dwarf planets at the edge can be nudged into new paths or ejected entirely, turning the outer map into a spray of wandering bodies. Some researchers have gone further, suggesting that Scientists reveal how Solar System might die in new white dwarf research, with Our solar system potentially pulled into the gravity of a passing white dwarf in an encounter that would be extremely catastrophic and violent. In that scenario, even the surviving giants could be torn apart or flung into interstellar space, turning the once orderly Solar System into dust and rogue planets.

White dwarf afterlife and the search for new maps

Once the red giant has exhausted its fuel and blown off its outer layers, the Sun will shrink into a white dwarf, a dense stellar ember about the size of Earth but with roughly half the Sun’s current mass. Around that remnant, the surviving planets and debris will trace out a new, colder architecture that is only now coming into focus through observations and theory. Some of the most intriguing work suggests that Feb research on white dwarfs indicates exciting habitable exoplanets might actually exist around white dwarfs and not other types of stars, and there is maybe even a chance that such worlds could host long lived atmospheres.

To understand how our own system might look in that phase, astronomers are turning to both telescopes and simulations. One recent visualisation, highlighted when NASA reveals a terrifying glimpse into the Solar System’s fate, shows a shrunken white dwarf Sun surrounded by a sparse ring of surviving planets and rubble. Audio explainers such as the WION Podcast on the violent end of our Solar System describe how Scientists reveal a violent and chaotic future for our solar system, as the Sun runs out of fuel in stages and As the Sun evolves, the map of our neighbourhood is redrawn again and again. I find that the most unsettling part of this picture is not the final white dwarf itself, but the long, messy transition, a reminder that even seemingly permanent cosmic structures are only temporary arrangements of matter and gravity.