Deep inside a limestone hill on an Indonesian island, a faded outline of a human hand has just pushed the story of art back tens of millennia. The claw-like stencil, dated to roughly 67,800-years-old, is now the earliest known example of rock art anywhere on Earth, forcing archaeologists to rethink when and where symbolic creativity first took hold. Instead of beginning in Ice Age Europe, the history of images on stone now starts in a tropical cave overlooking the seas of Southeast Asia.

The discovery does more than add a new record to the timeline. It shows that by nearly 70,000 years ago, people in this region were already using pigment, planning compositions and perhaps telling stories on cave walls, long before the famous bison of Altamira or the lions of Chauvet. In the narrow negative space around a single hand, I see an entire chapter of human imagination being rewritten.

The clawed hand that reset the clock

The new record holder is a ghostly hand shape with unnaturally long, narrow fingers, sprayed in red pigment around a palm pressed to the rock. Researchers working in Sulawesi describe it as a claw-like drawing of a human hand, and dating of mineral crusts that formed on top of the pigment shows it is about 67,800-years-old, making it the World’s oldest-known rock art by a wide margin compared with earlier finds in Europe and Asia, according to detailed reporting on the oldest rock art. The outline is not a casual smudge, it is a deliberate stencil, created by blowing or spitting pigment around a hand to leave a negative silhouette that still clings to the cave wall.

At the site known as Liang Metanduno, archaeologists have identified multiple stencils, but one stands out as the earliest, with uranium-series measurements on overlying calcite crusts indicating an age of at least 67,800 years, a figure that is echoed in reports describing the World’s oldest cave art as a 67,800-year-old hand stencil found in Indonesia and in coverage that calls these hand stencils the oldest-known rock art at Liang Metanduno in Sulawesi, Indonesia, where the cave lies just inland from coral reefs and diving spots that now attract tourists, as described in accounts of Archaeology World. The same work notes that the faint image is part of a broader panel of handprints and animal figures, suggesting that even at this early date, people were composing scenes rather than leaving isolated marks.

How scientists proved it is nearly 70,000 years old

To turn a ghostly outline into a data point on the human timeline, researchers needed a reliable clock, and they found it in the thin crusts of calcium carbonate that had formed naturally over the paintings. By sampling these layers, labelled Samples LMET1 and LMET2, and applying uranium-series dating, the team could calculate when the crust began to grow, which provides a minimum age for the pigment beneath, a process described in technical summaries of World’s Oldest Hand Stencil Art Discovered in Indonesia, Dating Back Nearly 70,000 Years that emphasise the role of these Samples and the figure of 70,000 Years as the upper range of the artwork’s antiquity, as outlined in analyses of Oldest Hand Stencil. This method avoids the contamination problems that can plague radiocarbon dating of ancient pigments, especially in humid tropical caves where organic binders may have long since degraded.

The same approach has been applied at other sites in Sulawesi, Indonesia, where researchers have identified an Oldest known rock art is a 68,000-year-old hand stencil with claws at newly documented caves, reinforcing the idea that this style of imagery was already established across the region by around 68,000-year-old, as described in coverage of Oldest known rock. Using this technique, which has been refined by teams including Indonesia based specialists and National Geographic Explorer Maxime Aubert, scientists can now push back the ages of rock art far beyond the 40,000 year limit of radiocarbon, a breakthrough highlighted in discussions of Indonesia’s new dating technique that underpins the 67,800-year-old hand stencil, as detailed in reports on Using this technique.

Indonesia and the shifting map of the “birthplace of art”

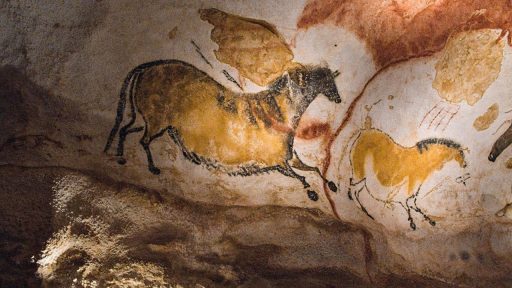

For more than a century, the story of early art has been anchored in Europe, where Ice Age galleries like Lascaux and Chauvet seemed to mark the moment humans began to think in truly abstract, symbolic ways, the kind of imagination that underpins religion, myth and eventually writing, a connection explored in analyses of how Cave art is seen as a key marker of when humans began to think in symbolic ways, as discussed in research on Cave art. The Indonesian handprints, however, are tens of thousands of years older than the famous European panels, and they sit within a broader cluster of early images across Indonesia and the surrounding region that now includes figurative scenes and animal outlines on Muna island, where scientists have described the World’s oldest cave art discovered in Indonesia’s Muna island as part of a wider pattern of early imagery in Indonesia and the surrounding region, according to reports on Indonesia and the. This geographic spread suggests that symbolic expression was not a late flourish of European hunter gatherers but a shared capacity among populations moving through Asia long before.

The implications are cultural as well as chronological, because the ochre hand stencil found in the jungles of Indonesia has been described as robbing Europe of its long held claim to be the birthplace of art, with commentators noting that the World’s oldest known cave painting now lies in a humid karst landscape rather than a French valley, a shift captured in commentary that credits Indonesia with overturning the old narrative, as summarised in analyses by Nick Squires. In that sense, the new dates do not just extend the timeline, they redraw the map, placing Indonesia at the centre of a story that once ran almost exclusively through Europe’s limestone hills.

What the handprints reveal about ancient minds

Even stripped of context, a hand stencil is a powerful image, a human presence without a body, frozen in negative space, and the Indonesian examples are no exception. Study co-author Adam Brumm told Reuters the claw-shaped design had some deeper cultural meaning but we do not know what that was, a reminder that while we can measure the age of the pigment, the beliefs behind it remain elusive, as he explained in interviews cited in a Study. The elongated, almost talon like fingers have prompted suggestions that the artist may have worn some kind of adornment or deliberately distorted the hand to create a supernatural effect, hinting at mythic or ritual ideas that are otherwise lost.

For archaeologists, what matters is that by at least 67,800 years ago, people in this part of Indonesia were already capable of using pigment, planning compositions and perhaps coordinating group activities around image making, behaviours that fit with the view that cave art is a key marker of symbolic thought and that such creativity may have emerged wherever Homo sapiens settled. Tens of thousands of years ago in what is now Indonesia, a human made their mark by placing their hand upon a cave wall, a scene evoked in public facing descriptions that invite viewers to imagine that moment of contact, as captured in social media posts about Tens of. When I look at the photographs of the Sulawesi stencils, I see not just an individual gesture but a community that recognised the power of leaving a durable sign of presence, perhaps as part of initiation rites, hunting rituals or storytelling sessions deep in the dark.