Biologists have long argued over which creature first split off from the common ancestor of all animals, a decision point that shapes how we picture the earliest animal bodies. Now a new wave of genetic sleuthing is bringing that first branch into sharper focus, suggesting a surprisingly alien starting point for the animal family tree. The result does not just reshuffle a diagram in a textbook, it forces a rethink of what it meant to be an animal in the deep past.

At stake is nothing less than the identity of our most distant animal cousins and the order in which key traits like nerves, muscles and guts emerged. By combining high resolution genome comparisons with fresh fossil evidence, researchers are converging on a picture in which some lineages that look simple today may actually be stripped down descendants of far more complex ancestors.

The fierce sponge–jelly rivalry at the root of animals

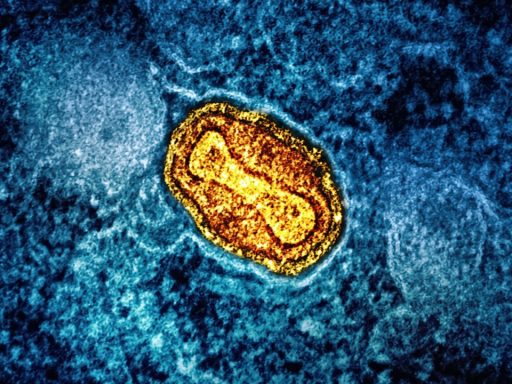

For more than a century, most biologists treated sponges as the obvious first branch of the animal tree, since they lack muscles, nerves and organized tissues and instead live as porous filter feeders. That tidy story has been under pressure as genetic data accumulate, with comb jellies, or ctenophores, emerging as a rival candidate for the earliest split from the common ancestor of animals, a debate that one detailed analysis described as a “fierce sponge–jelly battle” over which animals came. The answer matters because if comb jellies branched off first, then either complex features like nervous systems evolved more than once or they were lost in some lineages, both scenarios that overturn long held assumptions about how complexity arises.

In the latest work, a team led by Jan and colleagues leaned into this controversy by focusing not on individual genes but on how groups of genes are arranged along chromosomes in different animals. By comparing the placements of these conserved gene clusters in sponges and comb jellies to the patterns seen in other modern animals, the researchers could infer which arrangement was closer to the ancestral state and which looked more derived. Their conclusion, supported by a careful reconstruction of these genomic neighborhoods, points to comb jellies as the first branch, a result that has been highlighted in coverage of scientists finding the on the animal tree of life.

How genomes reveal the earliest split

The key to this new approach is that the order of genes along chromosomes tends to change slowly, even when the underlying DNA letters mutate rapidly. Jan and the team exploited this by tracking highly conserved gene neighborhoods across a wide range of animals, then asking which pattern required the fewest rearrangements to explain the diversity seen today. In their analysis, the comb jelly pattern fit more naturally as the starting point, while the sponge pattern demanded extra shuffling events, a sign that sponges likely diverged later from a lineage that had already experimented with more complex body plans. This strategy, which treats chromosomes as historical maps rather than just strings of letters, is described in detail in reports on how the researchers compared the placements of gene groups to reconstruct the earliest split.

Other genetic work points in the same direction. A separate group at the University of Vienna used a similar logic, comparing the arrangements of highly conserved gene sequences on chromosomes across multiple animal lineages to infer the order of evolutionary events between them. Their findings, which also support a scenario in which comb jellies diverged before sponges, help flesh out what the very first animals might have looked like by tying specific gene architectures to particular body plans. That study, which highlights the role of the University of Vienna team, reinforces the idea that the earliest animals were not just amorphous blobs but already carried the genetic toolkit for more elaborate forms.

Reimagining the first animals

If comb jellies really do sit on the first branch, then the earliest animals may have been more like translucent predators than passive sponges. Modern ctenophores are gelatinous swimmers that use rows of beating cilia to move and sticky cells to capture prey, and some possess nerve nets and muscle like tissues. The new genomic work suggests that at least parts of this lifestyle, including the genetic underpinnings of nervous systems, could trace back to the common ancestor of animals, with later lineages simplifying or elaborating those traits in different ways. Coverage of the study notes that Jan and colleagues see this as a major shift in how we picture the first animal bodies, a point underscored in summaries that explain how scientists have identified which modern group of animals best reflects that earliest split.

This reframing also affects how I think about the timing of key innovations. If the ancestor shared by comb jellies and all other animals already had a nervous system, then the absence of nerves in sponges and some other simple looking groups must be a secondary loss rather than a primitive state. That interpretation aligns with arguments that sponges, despite their apparent simplicity, show molecular traces of more complex machinery that has been pared back over time, a view explored in analyses of muscles and other in early branching animals. The result is a more dynamic picture of early evolution, in which complexity can ebb as well as flow.

Fossils that hint at lost branches of life

Genomes are not the only lines of evidence reshaping the tree of life. Paleontologists working in Scotland recently revisited a giant fossil organism known as Prototaxites, which towered up to eight meters high and lived around 400 million years ago. For decades, Prototaxites defied classification, with arguments over whether it was a plant, an alga or something else entirely. A new analysis of exceptionally preserved specimens, published in Science Advances, concludes that Prototaxites belonged to a lineage that sits outside modern plants, animals and fungi, effectively revealing an extinct branch of complex life that we only know about through these exceptionally preserved fossils.

Another team, including researchers from the University of Edinburgh, has described an extinct species that also reached about eight meters in length and inhabited Earth roughly 400 million years ago, before the first trees appeared. Their study, framed as work that rewrites evolutionary history, emphasizes how such giants fit into ecosystems that predate modern forests and familiar animal groups. The involvement of the University of Edinburgh highlights the growing collaboration between paleontologists and evolutionary biologists who are trying to map not just the surviving branches of life but also the many that ended in extinction.

Why the first branch matters far beyond biology

Putting these threads together, I see a pattern in which both genomes and fossils are revealing a tree of life that is bushier and stranger than the tidy diagrams many of us learned in school. The identification of comb jellies as the earliest animal offshoot, supported by Jan’s chromosome based comparisons and the University of Vienna’s gene arrangement work, dovetails with discoveries like Prototaxites and the giant eight meter species in Scotland to show that entire ways of being alive have come and gone. Popular explainers have seized on this theme, noting that scientists have effectively found the first branch among animals at the same time that paleontologists are sketching in lost branches elsewhere on the tree.

The stakes extend beyond academic classification. Knowing which lineage branched off first shapes how medical researchers interpret model organisms, how conservation biologists prioritize evolutionary distinct species and how educators tell the story of life’s origins. When I read that the fossil of a Cambrian animal can illuminate the extinction of entire worlds of organisms, as some reports on early animal fossils have put it, I am reminded that our own branch is just one among many that could have been pruned. That sense of contingency runs through accounts of how the fossil of the era helps frame the rise and fall of animal groups, and it is echoed in the renewed attention to where, exactly, the animal tree first split.