High above the South Pacific, a NASA satellite recently caught a pale green plume blooming across the ocean’s surface, the visible signature of a violent eruption far below. The blast came from Kavachi, an active submarine volcano better known by its cinematic nickname, “Sharkcano,” where sharks have been documented living inside the crater itself. The new images confirm that this hidden volcano is once again reshaping the seafloor and the surrounding waters, even as scientists race to understand how life survives in such an extreme place.

The eruption, captured from space in striking detail, turns an obscure seamount in the Solomon Islands into a global laboratory for studying how oceans, geology and biology intersect. It also highlights how modern Earth‑observing tools are giving researchers a front‑row seat to events that would be almost impossible, and deeply dangerous, to witness up close.

The hidden volcano beneath the Pacific

Kavachi rises from the seafloor in the southwest Pacific Ocean, south of the Solomon Islands and east of Papua New Guinea, where the Pacific tectonic plate dives beneath its neighbors and fuels intense volcanic activity. The volcano’s summit is believed to sit only a few dozen meters below the surface, making it one of the most accessible, yet still largely unreachable, underwater volcanoes in the region. Satellite and shipboard observations have shown that this restless seamount has built and destroyed small ephemeral islands multiple times as eruptions pile up loose ash that is then quickly eroded away by the ocean’s waves.

Scientists classify Kavachi as one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the Pacific, a status underscored by repeated eruptions recorded over the past two decades. The feature, sometimes referred to locally as “Kavachi’s Oven,” lies within the territory of the Solomon Islands, a Pacific island nation whose scattered archipelagos sit along a major tectonic boundary. Detailed descriptions of the volcano’s location and behavior have been compiled by regional surveys and by NASA Earth Observatory, which has tracked its changing shape from orbit.

A fiery plume seen from space

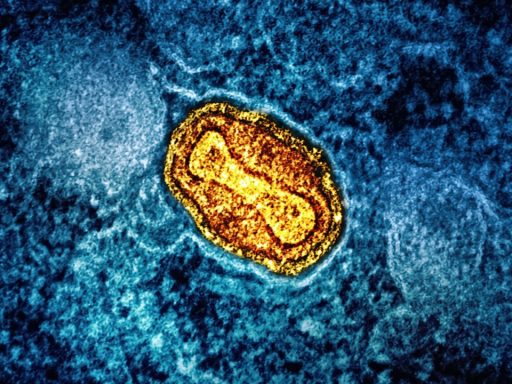

When Kavachi roared back to life, NASA’s instruments were in the right place at the right time. A satellite image from the Landsat 9 mission showed a milky, discolored patch of water fanning out from the volcano’s summit, a classic sign of a submarine eruption pushing ash, rock fragments and volcanic gases into the sea. The pale plume stretched for several kilometers, its color contrast against the deep blue Pacific making the disturbance easy to spot from orbit. The eruption was energetic enough that the feature was visible even in relatively low‑resolution imagery, underscoring the power of the blast beneath the waves.

The discolored water around the vent, documented in detail by NASA Landsat data and highlighted in satellite analysis, likely contains a mix of superheated water, fine ash and minerals that alter the ocean’s chemistry in the immediate area. Another sequence of images, shared in coverage of the Sharkcano eruption, shows how quickly the plume can spread and dissipate as currents carry volcanic material away from the vent.

Why scientists call it “Sharkcano”

Kavachi would already be a compelling subject for geologists, but its most famous residents have turned it into a scientific curiosity with global name recognition. During expeditions in the past decade, researchers sent robotic cameras into the volcano’s flooded crater and were stunned to find large marine animals thriving in the hot, acidic and ash‑filled water. Footage revealed hammerhead sharks and silky sharks swimming calmly through the turbulent interior, along with other species such as bluefin trevally and jellyfish, in conditions that had been assumed to be too extreme for such creatures.

The presence of these predators inside an active crater led scientists to dub the site “Sharkcano,” a nickname that has since stuck in both scientific and popular accounts. Reports on the discovery describe how volcano earned this after sharks were documented living in its acidic waters, while later summaries emphasize that sharks surviving inside challenge long‑held assumptions about marine resilience. A separate account of a National Geographic expedition describes hammerhead and silky sharks enduring temperatures that can exceed 400°F in parts of the hydrothermal system, underscoring just how hostile the environment can be.

Life on the edge of habitability

From a biological perspective, Sharkcano is a natural experiment in how life adapts to extremes. The crater water is laced with sulfur, ash and volcanic gases, and its temperature and acidity can change in seconds as new pulses of magma reach the seafloor. Earlier research into submarine volcanic plumes has shown that they can carry particulate matter, rock fragments and sulfur compounds that would normally be considered toxic at high concentrations. Yet in Kavachi’s case, these conditions appear to support a specialized ecosystem that includes not only sharks but also smaller fish, microbes and invertebrates that form the base of a unique food web.

Scientists are still working to understand how these animals tolerate such stress, and whether they move in and out of the crater in response to changing activity. Accounts of the volcano’s ecology note that bluefin trevally and share the crater with jellyfish and other species, while a detailed summary of the site’s biology emphasizes that Kavachi Volcano is unusual precisely because of the creatures that call it home. Another overview of the system stresses that scientists believe the lies close enough to the surface for light to penetrate, which may help sustain photosynthetic microbes that in turn support higher life forms.

What the eruption reveals about Earth’s restless oceans

Beyond its charismatic sharks, Kavachi offers a window into how submarine volcanoes influence the broader ocean environment. Each eruption injects heat, minerals and gases into the water column, altering local chemistry and potentially affecting marine life over a wide area. The discolored plume seen in the latest satellite images is not just a visual spectacle, it is a sign of active geochemical exchange between the Earth’s interior and the sea. Over time, repeated events like this can build new seafloor, change habitats and even affect regional fisheries if nutrient levels shift significantly.

Remote sensing has become essential for tracking these changes, since direct observation is so risky. The recent eruption was documented by NASA photos that captured the underwater blast, while other analyses of Kavachi Volcano place it within a global context of active submarine systems. Coverage of the event has highlighted how NASA and other agencies now routinely monitor such eruptions, while technical briefings on satellite imagery explain how sensors can distinguish volcanic plumes from ordinary ocean color changes. Additional context from tectonic studies notes that Kavachi formed in a particularly active subduction zone, while climate‑focused reporting on submarine plumes underscores how such systems can influence ocean chemistry at the surface as well as at depth.