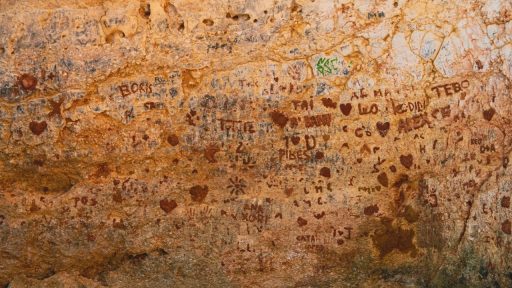

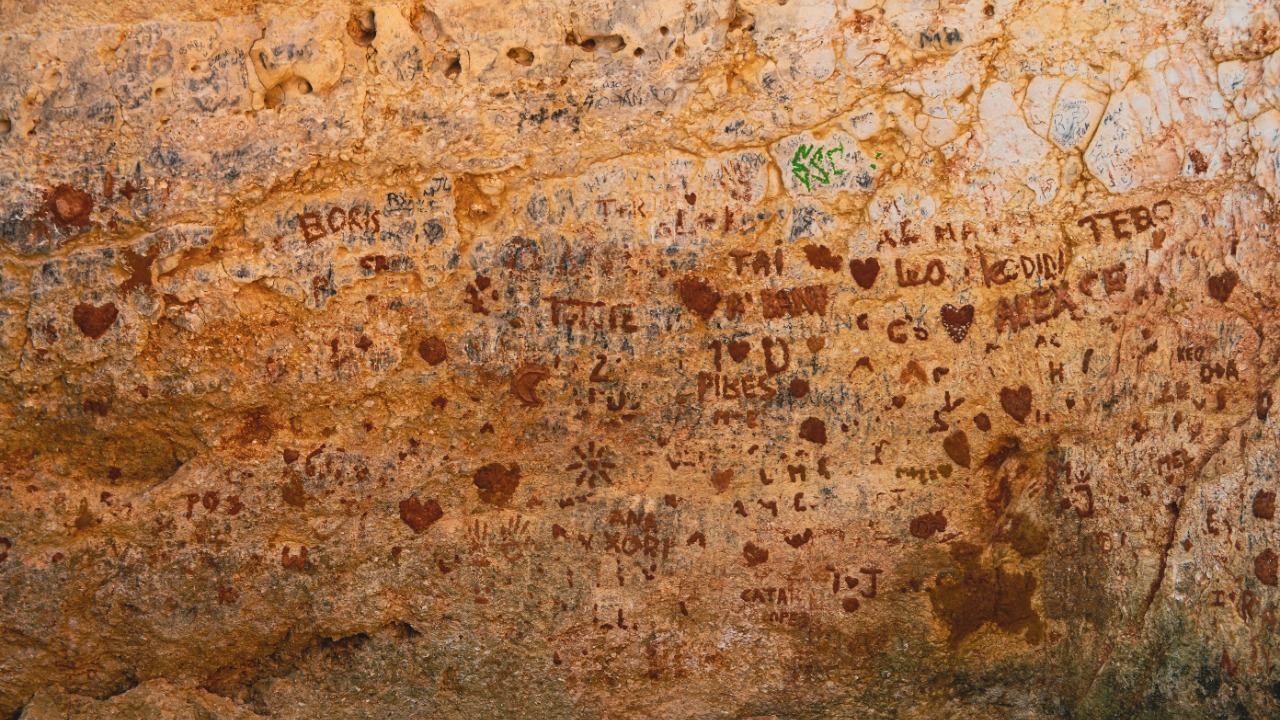

Deep inside a limestone cavern in Indonesia, a single human hand pressed against rock at least 67,800 years ago has rewritten the story of art. The faint outline, created when someone blew pigment around their fingers, now stands as the world’s oldest known cave image and a direct trace of symbolic thought long before Europe’s famous Ice Age paintings. By pushing visual culture tens of millennia further back in time, the discovery forces me to rethink where, and how early, our species began to picture itself.

The hand stencil, dated to a minimum age of 67,800 years, is more than a scientific milestone. It anchors Indonesia at the center of a global debate over when modern human creativity emerged, and it links distant islands to the deep ancestry of communities that would one day spread across Australasia. In a single negative print, I see both the intimacy of an individual gesture and the vast sweep of human migration.

The 67,800-year-old hand that changed the timeline

Archaeologists working on an Indonesian island have identified a hand stencil that they date to at least 67,800 years, a figure that instantly eclipses the ages of celebrated European cave paintings. The image is a negative outline, created when a person placed their palm on the wall and sprayed pigment to leave a ghostly border, a technique that appears again and again in later prehistoric art. Researchers describe it as the oldest known cave painting, a status that turns this anonymous individual into the earliest identified artist on record.

Visuals shared by Archaeologists show the stencil tucked inside a cave near the coast of Sulawesi, part of a broader cluster of rock art sites in the region. Social media clips frame it as a “67,800-Year-Old Hand Stencil Discovered” and highlight how the find has been verified as the “World’s Oldest Cave Art,” language that captures the excitement but also the high stakes of the claim. For specialists, the key point is that this is not an isolated oddity but a carefully dated piece of a larger prehistoric landscape.

How scientists proved the age of Indonesia’s rock art

Establishing that a painting is tens of thousands of years old is far from straightforward, and the Indonesian handprint owes its status to advances in geochemical analysis. Researchers sampled mineral crusts that had formed over the pigment and applied a technique that measures the decay of uranium into thorium, a method that sets a firm minimum age for the art beneath. By focusing on these thin calcite layers rather than the pigment itself, they avoid contamination that can plague older dating approaches and push the timeline deeper into the past.

Reporting on the project notes that the team relied on uranium-series analysis to reach the 67,800 year figure, a level of precision that gives the claim unusual weight. One of the scientists involved, identified as National Geographic Explorer, has been at the forefront of applying this method in Indonesia, where the humid climate and active geology make preservation a constant challenge. For me, the technical rigor behind the date is what transforms a striking image into a cornerstone of human history.

Indonesia’s caves emerge as a cradle of symbolic art

The Sulawesi handprint is not an isolated marvel but part of a growing body of evidence that Indonesia was a major center of early symbolic expression. Archaeologists have uncovered a series of rock art sites in Sulawesi that include not only hand stencils but also animal figures and abstract motifs, all tucked deep inside caves that would have required planning and cooperation to access. These compositions suggest that communities here were investing time and resources in images that carried shared meaning.

One account of the fieldwork describes how teams ventured “deep inside a cave in Sulawesi” to document panels that challenge long-held assumptions about where art began, arguing that early humans in this region were just as inventive as their European counterparts. The same report notes that the discovery directly challenges theories that placed the origins of artistic expression solely in Europe. When I look at this pattern of finds, it becomes harder to see cave art as a regional quirk and easier to view it as a widespread feature of early Homo sapiens culture.

From Sulawesi to Muna Island, a wider Indonesian rock art frontier

The story of Indonesia’s ancient imagery now extends beyond Sulawesi to other islands that dot the country’s vast archipelago. Researchers from Indonesia and Australia have reported the oldest known cave painting in Metanduno Cave on Muna Island in Southeast Sulawesi, adding another early masterpiece to the map. Indonesia has confirmed that this Metanduno panel forms part of the same deep-time artistic tradition, reinforcing the idea that rock art flourished across multiple islands rather than in a single isolated pocket.

Officials and scientists have framed these finds as a national milestone, describing the Metanduno discovery as part of a “worldoldestcaveart” narrative that links Muna Island to Sulawesi’s more famous sites. In parallel, other teams have highlighted how the Sulawesi hand stencil, described in one reel as the World Oldest Cave and a “67,800-Year-Old Hand Stencil Discovered,” fits into a broader Indonesian push to document and protect prehistoric heritage. For me, the spread of sites from Sulawesi to Muna Island suggests that early seafaring populations carried shared symbolic practices as they moved between coasts and caves.

What the world’s oldest cave art reveals about us

Placing a hand on stone and outlining it with pigment is a simple act, yet it speaks volumes about the mind that performed it. Archaeologists argue that the 67,800-year-old stencil reflects a capacity for abstraction and shared symbolism, qualities that underpin language, religion and social identity. One report on the find stresses that the work of Indonesian specialists has direct implications for how we understand the origins of human symbolic creativity, since it shows that such behavior was present far earlier, and in more places, than once assumed.

Other researchers emphasize that the stencil is part of a wider pattern of early imagery that carried meaning among ancient communities. One synthesis notes that Archaeologists now see these Indonesian caves as evidence that symbolic marks helped cement group identity and transmit knowledge long before writing. Another analysis argues that the discovery “places Indonesia as one of the most important centers in the early history of symbolic art and modern human seafaring,” a phrase that links the handprint to the ancestors of indigenous Australians and underlines the region’s role in early ocean crossings, as highlighted in that assessment. When I picture that ancient hand, I see not only an individual asserting “I am here” but also a community experimenting with the visual language that would eventually shape every culture on Earth.