Earth’s magnetic field has just pulled off a quiet but profound rearrangement, shifting the north magnetic pole into a region of the Arctic that scientists have never before had to chart. The move pushes navigation systems, climate researchers and even aurora watchers to adapt to a planet whose invisible magnetic scaffolding is far more restless than most of us realize. I see this jump into never-mapped territory as a reminder that the ground truth beneath our compasses is a living, shifting system, not a fixed backdrop.

The pole that refused to stay put

For generations, schoolroom globes have lied by omission, suggesting that north is a permanent point rather than a moving target. In reality, the magnetic pole has wandered since long before British explorer Sir James Clark Ross first pinned it down in 1831 in northern Canada, roughly 1,000 miles from the geographic pole. Earlier accounts describe how James Clark Ross, sometimes styled as Sir James Clark Ross, trekked to the Boothia Peninsula to mark the spot, a location that has since drifted so far that the original site is now a historical footnote rather than a navigational reference.

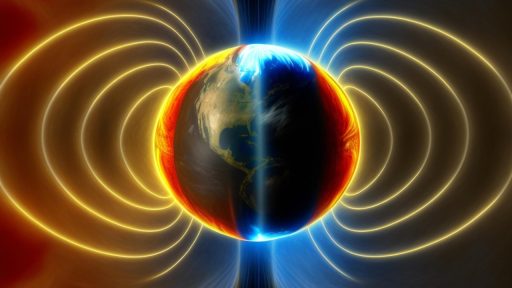

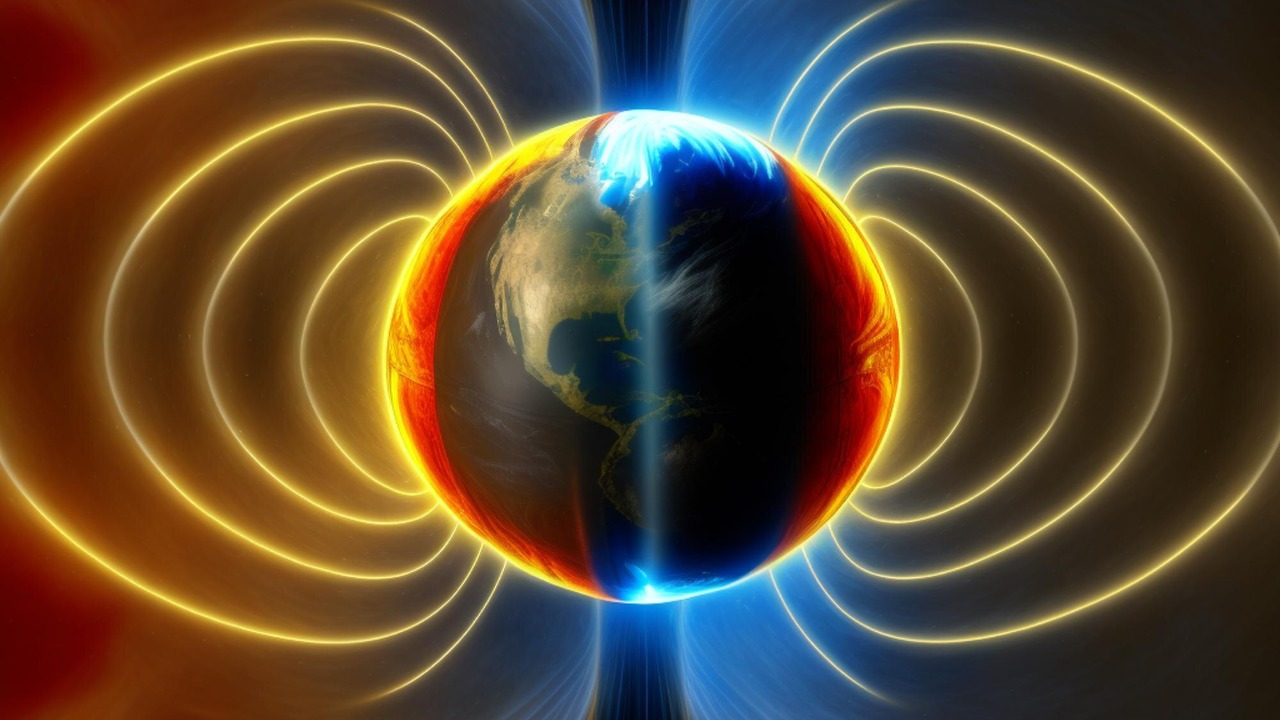

Since Earth’s field is generated by molten iron moving in the outer core, the poles are inherently mobile, a point captured in the simple phrase “Since Earth” scientists began tracking the wandering pole in detail. Historical reconstructions show that for much of the twentieth century the north magnetic pole crept along at only a few miles per year, a sedate pace that lulled mapmakers into assuming slow, predictable change. That assumption has now been shattered by the latest shift, which confirms that Earth’s Magnetic North Pole Has Officially Changed Position, Drifting Into Never, Before, Mapped Territory according to new analyses of the field drift.

From Canadian Arctic to a Siberian pull

The story of this leap into uncharted space begins in the high Canadian Arctic, where the pole once lingered near the Boothia Peninsula. Historical reconstructions show that it started in Canada and then began inching closer to Siberia, a journey that has now carried it across an invisible frontier in the Arctic that researchers had never seen it occupy. One detailed account notes that the magnetic north pole just is not where it used to be, tracing a path that began near the Boothia Peninsula and now arcs toward Russia, a trajectory that matches satellite and ground observations of the core-driven drift.

Researchers describe the current position as having crossed an invisible “border” in the Arctic, a threshold that separates the familiar Canadian side of the polar basin from a sector where They, meaning the teams tracking the pole, have never seen it settle before. Reports on this crossing emphasize that Earth’s magnetic north pole has entered a region that earlier models did not anticipate, raising the question not of whether it is moving, but what will happen when the North Pole, in the magnetic sense, continues deeper into this new sector of the Arctic.

Why the sprint is speeding up

To understand why the pole is racing instead of strolling, I look beneath our feet, into the churning outer core. One influential explanation frames the motion as a tug-of-war between two patches of strong magnetic field under Canada and Siberia, with the balance between them shifting over time. Using data collected over two decades by satellites, including ESA’s Swarm trio, researchers at Leeds have shown that the position of the north magnetic pole reflects subtle changes in this deep competition between the core and mantle under Canada and Siberia.

Other work points out that Earth, sometimes written as Earth (the Earth), hosts two relatively strong magnetic patches that help anchor the pole, and that as their strengths wax and wane, the pole can lurch back and forth. Earth (the Earth) scientists have long known that the exact position of the pole is related to these patches, and recent modeling suggests that the current sprint toward Siberia reflects a rebalancing that favors the Russian side of the Arctic basin. In that context, the pole’s new position is not a random jump but the latest step in a long-running oscillation that has now carried it into a part of the field that earlier generations of scientists never had to map.

How navigation keeps up with a moving target

The pole’s sprint is not just a curiosity for geophysicists, it is a practical headache for anyone who relies on compasses, from smartphone apps to aircraft. Unlike the geographic North Pole, which is fixed at Earth’s rotational axis, magnetic north shifts unpredictably, which means that navigation systems must constantly adjust for the difference between true and magnetic bearings. One analysis stresses that, Jan aside, the key point is that Unlike the geographic North Pole, magnetic north can drift in ways that are hard to forecast, a reality that has prompted renewed attention to how pilots, mariners and even hikers calibrate their navigation.

To keep up, Scientists from NOAA and the British Geological Survey have just released an updated World Magnetic Model, or WMM, recalibrating where compasses point for everything from Google Maps to the guidance systems on commercial jets. These Scientists rely on a blend of satellite readings, ground observatories and Survey campaigns to refine the WMM, which is the quiet backbone of modern navigation. The latest update reflects the fact that Earth’s Magnetic North Pole is no longer where older models assumed, forcing a recalculation that ripples through every device that depends on the model.

Experts who maintain the World Magnetic Model note that they usually update it every five years, but the recent acceleration has already forced early revisions. Experts around the world collaborate on this WMM, which is a crucial tool that maps the shifting magnetic landscape and allows users to convert between magnetic and true bearings. Historically, the magnetic North Pole has drifted slowly around Canada, but its recent sprint toward Siberia has pushed the WMM to its limits, prompting a fresh look at how often the global community should refresh this shared reference.

Everyday consequences, from runways to road trips

The most immediate impacts of the pole’s new position show up in subtle ways that most travelers never notice. Airport managers periodically rename runways when the magnetic heading shifts enough that the painted numbers no longer match pilots’ compasses, a process that will accelerate as the pole continues its sprint. One vivid illustration of how misalignment can accumulate comes from a scenario in which Scientists say that if you tried traveling the 5,280 miles from South Africa to the United Kingdom in a straight line using outdated magnetic data, you could end up significantly off course, a reminder that long-distance routes are especially sensitive to small errors in declination.

Even for casual users, the shift matters. Knowing that declination for points across the globe allows one to convert between a magnetic bearing and a true bearing, according to detailed technical guidance, and that conversion is baked into everything from hiking GPS units to the compass app on an iPhone. Earth’s north magnetic pole is moving fast enough that these declination values can drift by a degree or more within a few years, which is why the WMM had to be updated ahead of schedule to keep navigation software and paper charts in sync with the real field.