The orbital debris scare of 2025 was not a fluke. It was the predictable result of packing low Earth orbit with hardware faster than governments and companies are willing to clean it up. I see a widening gap between the urgency exposed by that emergency and the slow, fragmented rollout of the technology and rules that could actually make space safer.

The 2025 scare showed how fragile orbit has become

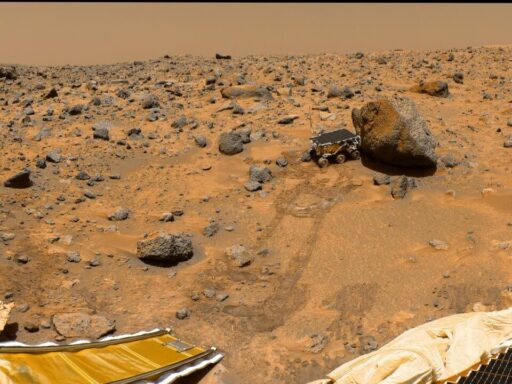

What happened in 2025 was a warning shot from a crowded sky. Spacecraft operators suddenly had to scramble when a cloud of fragments drifted toward a busy orbital lane, forcing last minute maneuvers and putting both billion dollar assets and human lives at risk. Space debris experts now estimate that nearly half of the junk in low orbit traces back to fragmentation events and the legacy of anti satellite weapons testing, a pattern that turned one incident into a systemic alarm rather than an isolated mishap, as detailed in the account of the orbital emergency.

The scale of the problem is staggering. Analysts now talk about 130 Million Debris Objects in Orbit, One Just Cracked A Spacecraft Window, a reminder that even microscopic fragments can compromise a vehicle and the people inside it. Scientific assessments count approximately 45,300 trackable objects larger than ten centimeters between low and geostationary orbit, with countless smaller shards adding to what researchers bluntly describe as The Growing Threat of Orbital Congestion. From my vantage point, the 2025 scare simply made that invisible minefield impossible to ignore.

Cleanup tech is real, but still mostly in demo mode

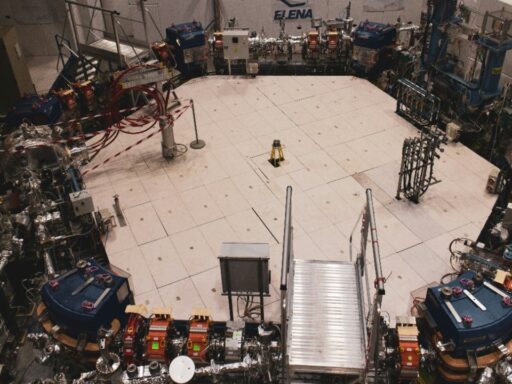

On paper, the hardware to start cleaning up this mess already exists. In practice, it is still inching toward operational scale. The European Space Agency is preparing the ClearSpace 1 mission to capture and deorbit ESA’s 95 kg PROBA 1 satellite, a small but symbolically important step to keep a valuable low Earth corridor from accumulating more junk, as described in the mission profile for ESA PROBA Earth. The same project sits inside an Overview of ESA Space Safety Programme Active Debris Removal Orbit Serv, which is meant to seed a commercial in orbit servicing market rather than remain a one off science experiment.

Private players are pushing similar demonstrations. Astroscale has already flown its ELSA d mission, formally titled Sep Astroscale ELSA Finalizes De Orbit Operations Marking Successful Mission Conclusion, which proved that a chaser satellite could locate and magnetically dock with a client object before guiding it toward reentry, a milestone that underpins the company’s future plans for grappling another satellite in 2026. Engineers documented the rendezvous and proximity maneuvers as RPO Operations that required Synchronized control of two spacecraft in constant contact with teams in Japan and the manufacturer SSTL, a level of choreography that is captured in the technical briefing on RPO Operations Synchronized Japan SSTL. From my perspective, these missions prove the physics and guidance software, but they do not yet amount to a fleet that can keep up with the rate at which new debris is created.

Policy, money and politics are slowing the fix

The bottleneck now is less about engineering than about incentives and law. Even as Swiss startup ClearSpace lines up a commercial launch on a Euro rocket with Arianespace, a partnership highlighted in the announcement that Swiss Arianespace Euro, there is still no binding global rule that forces satellite operators to pay for end of life disposal. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty established that states retain ownership of their objects in orbit, a principle that complicates any attempt to grab someone else’s derelict hardware and that modern experts now cite under the banner of a Need for Regulations Outer Space Treaty. Without a clear legal pathway, every debris removal mission becomes a bespoke diplomatic negotiation.

Funding models are just as unsettled. Astroscale has secured public and private backing for its next generation ELSA m spacecraft, with investors encouraged to Share this article, Join the conversation, Follow the company and Add it as a preferred source on Google as part of a broader push to commercialize multi client cleanup services, a strategy outlined in the pitch for Jul Share Join the Follow Add Google. The firm has also finalized a contract for a Japanese debris removal mission, a deal reported in late Aug that executives say will only become profitable as research and development costs fall and margins improve by up to 50 percent, according to the update on Aug. From where I sit, that is a sign that the business case is still fragile, dependent on government anchor customers rather than a broad market of private buyers.

The clock is ticking faster than the solutions

Meanwhile, the debris environment keeps deteriorating. Analysts in Hoboken warn that millions of human made objects, large and small, are now flying through Earth’s orbit at speeds that can shred a spacecraft, and they stress that fragments larger than one centimeter pose a serious threat to future missions, a risk spelled out in the research on how Hoboken High orbital junk endangers exploration. Other specialists frame the issue as a Problem Statement titled Why We Have So Much Space Debris Now, pointing to the rapid growth of constellations in Earth orbit and the vast population of objects smaller than ten centimeters that are effectively invisible to current tracking networks, a diagnosis laid out in the analysis of Aug Problem Statement Why We Have So Much Space Debris Now Earth. I read those numbers and see a simple conclusion: mitigation rules alone will not be enough, active cleanup has to scale.

There are glimmers of that future. ESA permits four armed robots to start clearing space debris in 2026, authorizing a new generation of capture vehicles that can grab space debris with mechanical limbs instead of relying solely on nets or harpoons, a shift described in the plan for Feb ESA. Yet even as I watch these projects advance, I keep coming back to the central tension of 2025: the physics of orbital congestion are moving faster than the politics and economics of cleaning it up, and until that balance shifts, every new launch will carry the shadow of the next emergency.