Scientists are closing in on one of Alzheimer’s most stubborn problems: how to help the brain clear toxic plaques on its own. New work identifies molecular “switches” in the brain that appear to control a major cleanup enzyme, hinting at treatments that could restore a natural defense instead of simply slowing decline.

By tracing how these switches regulate the breakdown of amyloid beta, researchers are mapping a pathway that runs from individual receptors on brain cells to memory performance in living animals. The findings suggest that precisely tuning this system could one day help people keep plaques in check and protect their cognition.

Two brain receptors that act like on–off switches

At the center of the new research are two somatostatin receptors, SST1 and SST4, that act as control knobs for the brain’s handling of amyloid beta. Feb reports that researchers have identified these receptors as key regulators of neprilysin, an enzyme that breaks down amyloid beta, often abbreviated Aβ, which is a defining feature of Alzheimer plaques. When these receptors are active, neprilysin levels rise and the brain’s own machinery is better able to clear Aβ before it clumps into sticky deposits.

Dec coverage explains that the work, described as Scientists Discover Brain “Switches” That Help Clear Alzheimer Plaques, frames SST1 and SST4 as potential drug targets that sit upstream of this cleanup enzyme. Rather than trying to attack plaques directly, therapies could aim to nudge these receptors so that neprilysin ramps up inside vulnerable brain regions. That strategy would align treatment with the brain’s own design, using existing receptors and enzymes rather than introducing entirely new mechanisms.

How the switches control amyloid and memory

The clearest evidence that these receptors matter comes from animals in which they are missing. Jan reporting notes that When SST1 and, neprilysin levels fell, amyloid beta accumulated, and the mice developed memory problems that mirrored human Alzheimer symptoms. The chain is strikingly direct: remove the receptors, lose the enzyme, gain plaques, and see behavior change. That sequence reinforces the idea that these receptors are not just bystanders but active switches for the brain’s waste management system.

A more detailed slice of the work shows how this chain operates at the molecular level. One Feb analysis states that Researchers have identified receptors that increase neprilysin expression, and that neprilysin helps clear away Aβ before it aggregates into plaques that disrupt neural circuits. By tying receptor activity to both enzyme levels and measurable memory behavior, the studies move beyond correlation and build a mechanistic case that these switches sit at a critical junction between molecular cleanup and cognitive health.

Boosting the brain’s natural defense system

The emerging strategy is not to blast plaques with ever-stronger drugs, but to strengthen what Feb describes as the brain’s own Boosting the Brain Natural Defense System. In experiments that used genetically modified mice and laboratory models, activating SST1 and SST4 increased neprilysin, reduced amyloid buildup, and preserved memory performance compared with untreated animals. Those results suggest that the brain already has a powerful anti-Alzheimer toolkit, and that the real therapeutic challenge is learning how to flip the right switches at the right time.

Other research lines point to a similar philosophy. Work highlighted in Nov coverage of Boosting one protein shows that higher Sox9 levels improve plaque clearance and help the brain protect itself from Alzheimer, with Sox9 described as a Key Regulator of glial responses. Taken together with the SST1 and SST4 findings, these studies sketch a broader picture in which the brain’s own cells, including neurons and support cells, can be tuned to mount a stronger defense against Aβ without necessarily relying on external antibodies or broad immune suppression.

Linking receptors, cleanup enzymes, and microglia

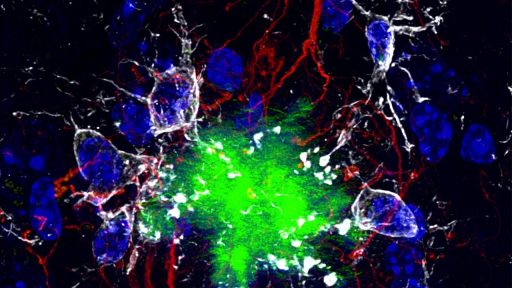

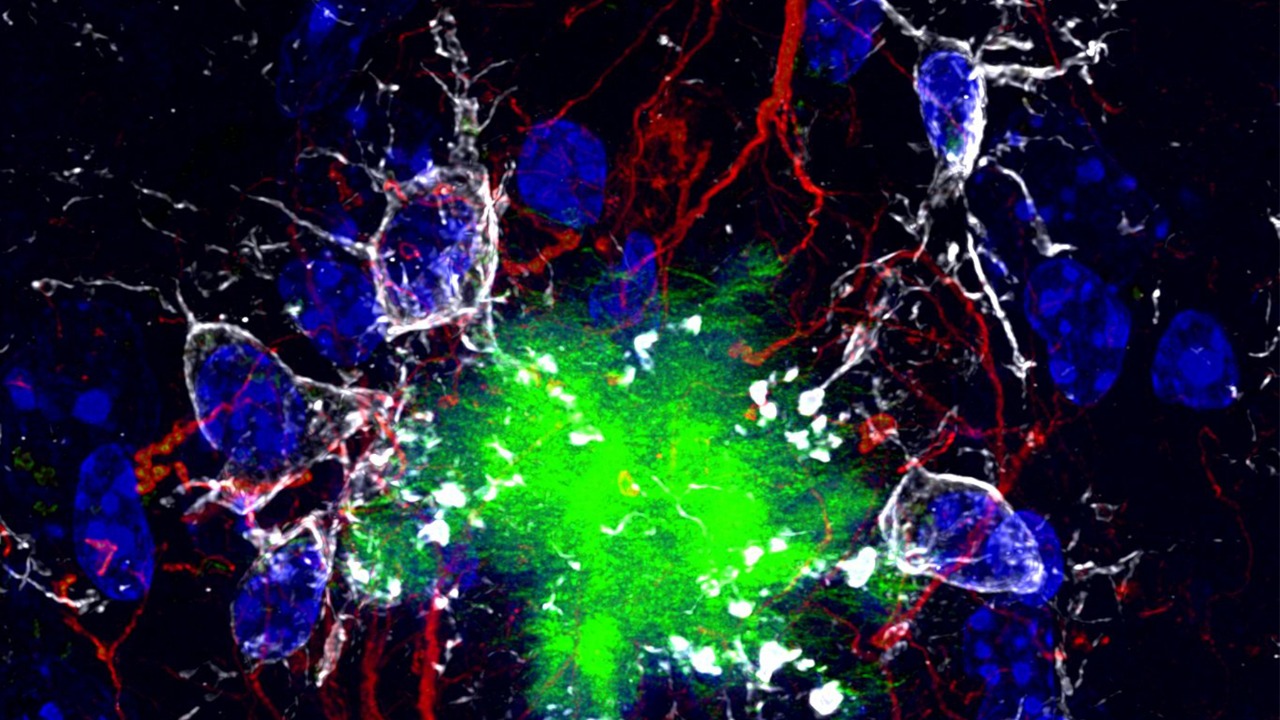

The new receptor findings also fit into a growing understanding of how different parts of the brain’s cleanup crew interact. Earlier work from Jul reports that Scientists at UCSF have shown how microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, can effectively digest toxic amyloid beta when a particular receptor pathway is engaged. That work focuses on microglial receptors rather than somatostatin receptors, but the logic is similar: specific molecular switches determine whether cells stay passive or gear up to clear harmful proteins.

Another set of findings, described in Feb coverage of Restoring the Alzheimer cleanup system, highlights a brain enzyme that sits behind recovery from plaque burden. That report emphasizes that memory loss in Alzheimer is often linked to sticky protein clumps and that the brain enzyme behind recovery must be balanced carefully so that benefits are not offset by side effects. The SST1 and SST4 work adds another adjustable dial to this network, suggesting that receptors, enzymes, and microglia form an interconnected system that can be tuned rather than hammered.

From lab discovery to potential treatments

Turning these molecular insights into real therapies will require a careful path that runs through basic science, drug development, and clinical testing. A research summary connected to discovery about brain notes that this line of work may open the door to new Alzheimer treatments by targeting receptors that sit on the surface of neurons and other brain cells, which are more accessible to drugs than intracellular enzymes. Because SST1 and SST4 are already known receptor types, pharmacologists can draw on decades of experience with somatostatin pathways in other conditions as they design compounds that selectively enhance the protective signaling linked to neprilysin.

Parallel efforts are exploring how to harness the brain’s cleaning systems more broadly. Nov reporting on Scientists Find a Way Help the Brain Clear Alzheimer Plaques Naturally describes approaches that encourage the brain to remove deposits and protect memory without heavy-handed interventions. Alongside the SST1 and SST4 receptor work, these strategies point toward a future in which clinicians might combine receptor-targeting drugs, enzyme modulators, and microglial therapies to keep amyloid beta under control across the course of the disease.