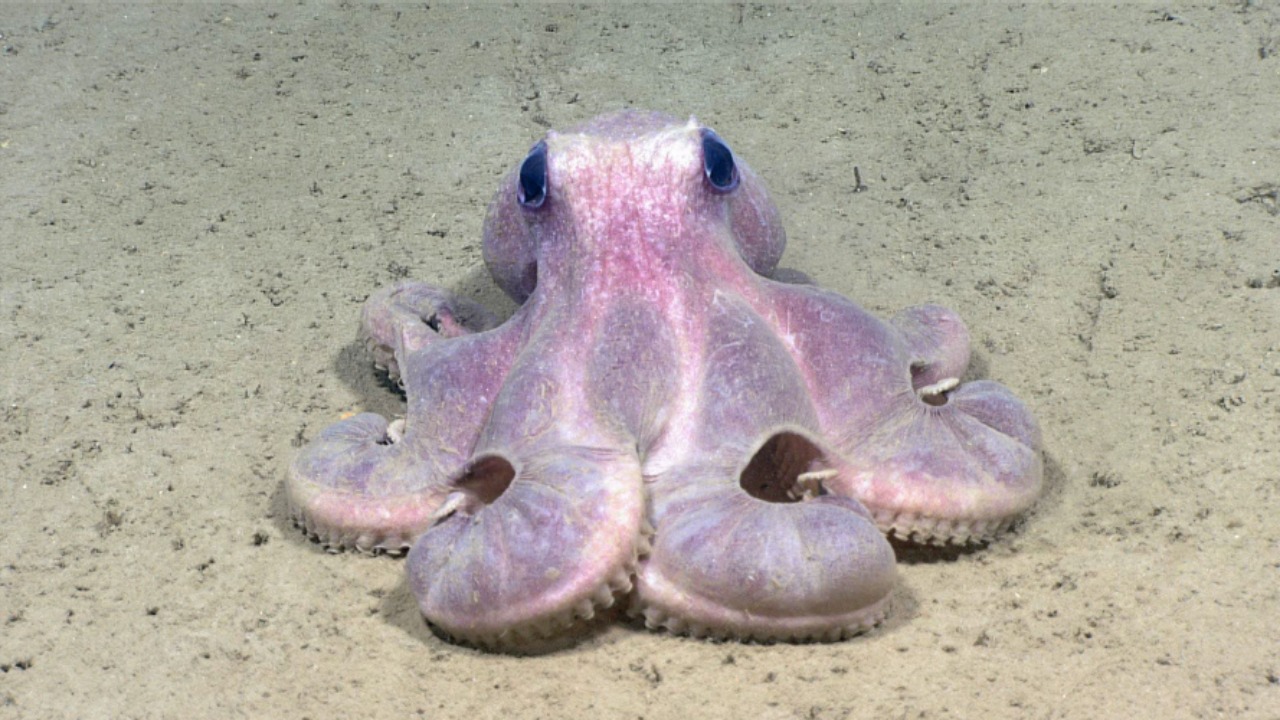

Off the south-west coast of the UK, 2025 turned into an underwater shock: common octopus numbers exploded to levels that veteran fishers and marine biologists had never seen in their lifetimes. What began as scattered reports of tentacled visitors in lobster pots has now been quantified in a major scientific assessment that explains why the surge happened, what it signals about the changing sea, and how coastal communities will have to adapt.

The new analysis shows that this was not a quirky one‑off but a rare ecological event with clear links to warming waters and shifting food webs. I see it as an early stress test of how fast marine life can reorganise around the UK, and how slowly our management systems are responding in comparison.

The scale of the ‘Year of octopus’

Scientists who compiled the 2025 octopus assessment describe a bloom that was as extensive as any previously recorded in the region, stretching across key fishing grounds off Cornwall, Devon and into the English Channel. The work, coordinated by researchers at the Marine Biological Association and partner institutions, drew on fishery landings, scientific surveys and reports from divers to map the sheer density of animals in south‑west waters, and the new report makes clear that this was a regional phenomenon, not a local quirk. A parallel analysis by a Plymouth‑based research team reached similar conclusions, describing the south‑west octopus bloom as unusually widespread and rooted in shared environmental drivers across the Channel, with researchers from across pooling data to capture its full footprint.

The numbers behind that map are stark. Landings of common octopus by commercial fisheries in the region last year were almost 65 times higher than recent annual averages, a figure that Cornwall Wildlife Trust and other groups have highlighted as evidence of a step change rather than a gentle uptick. One detailed study of catches reported that commercial landings in parts of South Devon and among Channel shellfishermen rose so sharply that octopus shifted from bycatch to a primary target species, with commercial catches dwarfing anything on record. When I look at those figures, it is hard to see the 2025 bloom as anything other than a structural shock to the local ecosystem.

Why the octopus boom happened

At the heart of the new findings is a simple but unsettling driver: warmer seas. Octopus breed in spring and summer, and they benefit from warm temperatures in those seasons, but the key to the 2025 surge lay in the preceding winters. Scientists point to a run of unusually mild winters in the north‑east Atlantic that reduced cold‑season mortality and allowed a much larger cohort of juvenile octopuses to thrive, a pattern that one synthesis dubbed the Year of octopus effect. The Plymouth climate analysis backs this up, linking the bloom years to unusually warm sea temperatures and to broader Climate patterns across the Channel that favoured octopus survival.

Layered on top of that background warming were shorter, intense bursts of heat in the sea itself. Marine scientists describe these as marine heatwaves, and they can stimulate rapid growth and reproduction in short‑lived species like common octopus. One analysis of the 2025 event notes that such marine heatwaves can trigger pulses of productivity that ripple through the food web, from plankton to fish to cephalopods. Warmer winters, which are linked to climate change, had already been flagged by conservation groups as a factor behind record octopus sightings in UK waters, with one account of the 2025 summer describing divers surrounded by animals in what was branded the Year of octopus. Taken together, the data show a climate‑driven push that set the stage for the boom long before fishers noticed tentacles in their pots.

Ecological shockwaves in the Channel

Once octopus numbers spiked, the ecological consequences spread quickly through south‑west food webs. Common octopus are voracious predators, feeding on crabs, lobsters, fish and shellfish, and the 2025 bloom coincided with reports of depleted shellfish beds and altered catch composition in key inshore grounds. The main scientific assessment notes that the bloom was tightly connected to cross‑Channel dynamics, with octopus moving between UK and continental waters and reshaping predator–prey relationships across the region, a pattern that the Channel fishing industry has already started to feel. Evidence of widespread breeding, including egg‑laden crevices and discarded shells with bite marks, suggests that the surge was fuelled by local reproduction as well as arrivals from further offshore, reinforcing the idea that south‑west habitats have temporarily tipped in favour of octopus.

There are signs that this predatory pressure has already cascaded down to other species. Some shellfishers have reported sharp local declines in crab and lobster catches, attributing part of the drop to intense octopus predation on juveniles and on animals held in pots. One industry‑focused analysis warned that in some inshore areas, the balance of value had flipped, with octopus now providing a significant share of income while traditional target species struggled, a shift captured in detail by Octopus Bloom Off. For me, the most striking ecological lesson is how quickly a short‑lived, fast‑growing predator can redraw the map of winners and losers in a warming sea.

Winners, losers and a nervous fishing industry

On the quaysides of Cornwall and Devon, the bloom has been both a windfall and a warning. Some skippers who had rarely seen octopus in their gear suddenly found holds full of high‑value catch, with monthly landings in the region surging far beyond historic norms. A policy briefing from Plymouth City Council notes that, prior to this year, monthly landings rarely exceeded 75 tonnes, a benchmark that was shattered during the bloom and used to argue that the surge is not a harmless blip but a sustained threat that needs long‑term planning. A separate assessment of regional landings, which found that the number of common octopuses landed last year was almost 65 times higher than recent averages, has been widely cited by marine biologists such as Bryce Stewart from the MBA as proof that management rules designed for a rare bycatch species are no longer fit for purpose.

At the same time, many inshore fishers are uneasy about building business models around a boom that may fade as quickly as it arrived. A non‑technical summary of the 2025 Octopus Report, shared with coastal communities under the banner Haven, stresses that while the current surge has brought short‑term income, it also raises questions about long‑term stock health, gear conflicts and market volatility. Broader commentary on the event has warned that octopuses are becoming an increasingly familiar presence in British waters after the 2025 surge, with scientists quoted as saying that rare blooms could become more common in UK seas and that Octopuses may remain at elevated levels compared with the past. From my perspective, the industry is being forced into a crash course on climate‑driven variability, with little guidance on how to hedge against it.

What happens next in a warming sea

Marine biologists are clear on one point: the 2025 bloom will not last forever in its current intensity. Octopus are short‑lived, with both males and females dying after breeding, which means their populations can swing sharply in response to environmental changes and fishing pressure. One synthesis of the event notes that The Surge Won Last Forever, but it also warns that, with a warming climate, heatwaves and the octopus blooms that follow are only going to become more likely as the species expands in response to rising temperatures. Another detailed analysis of the 2025 event underlines that the males also die after breeding and that this life cycle makes octopus populations highly affected by changes in environmental conditions, a point that Octo specialists have been stressing for years.