Generative AI promises instant answers on almost any topic, yet a new wave of research shows how shaky that promise becomes once you leave well‑trodden ground. Neanderthals, of all subjects, have become a sharp test of how these systems handle real scientific knowledge instead of pop‑culture stereotypes. By asking image and text models to recreate Neanderthal life, researchers have exposed a deep gap between confident output and actual scholarship.

The findings go far beyond prehistoric trivia, raising pointed questions about how schools, museums, journalists and ordinary users lean on chatbots and image generators for “good enough” explanations of the past. The Neanderthal case serves as a warning sign for anyone tempted to treat generative AI as a shortcut to expertise.

How Neanderthals became a stress test for AI

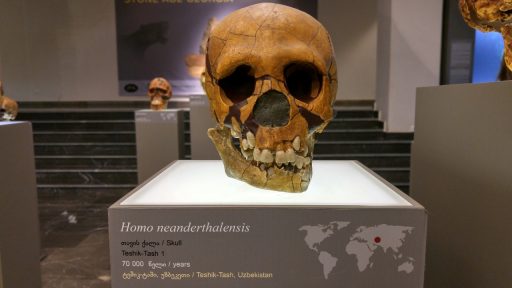

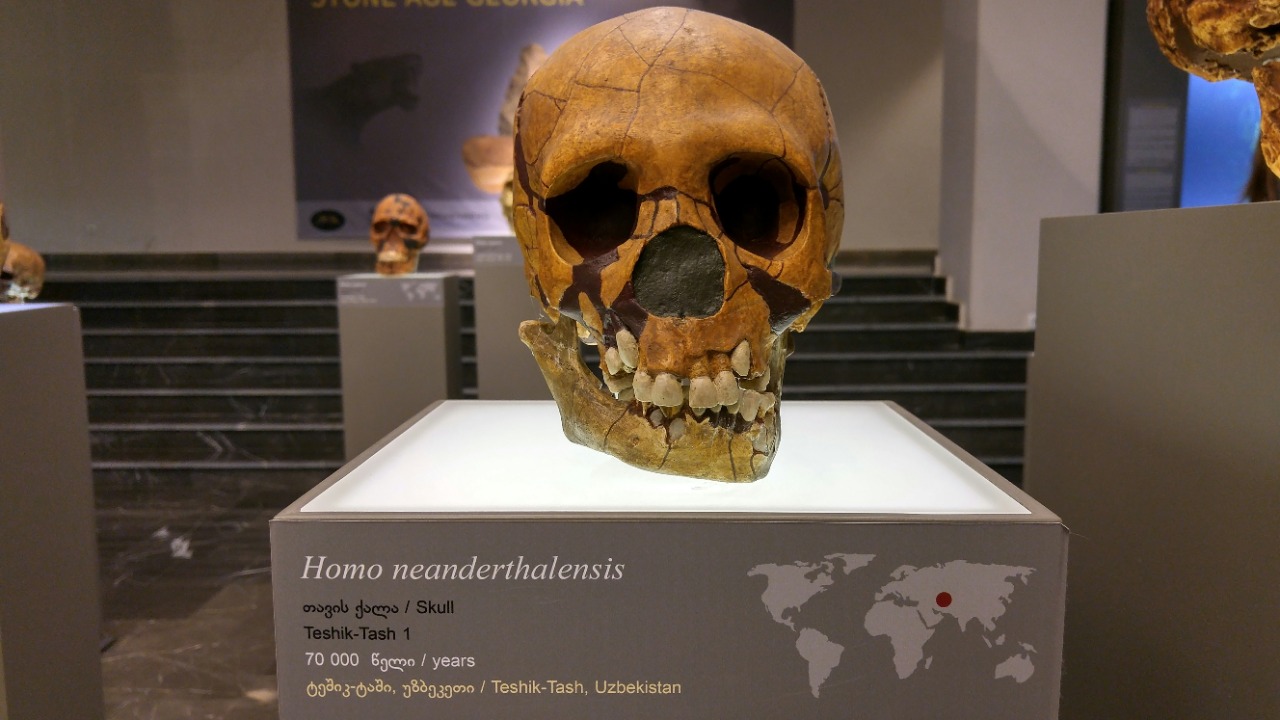

Researchers at The University of Maine treated Neanderthals as a kind of stress test for generative models because the science has moved fast while public images have lagged behind. They asked systems to describe and depict Neanderthal life, then compared the results to current archaeological work that appears in peer‑reviewed venues like Advances in Archaeological Practice. The project, described in a Feb report from the University of Maine, framed Neanderthals as a clear case where experts have overturned old myths about brutish cave dwellers, yet those myths still dominate movies, advertising and school posters.

This setup let the team measure how much AI systems lean on outdated cultural material instead of up‑to‑date research. According to the New study, the models often missed basic points about Neanderthal culture, such as evidence for complex tools and social care, even though those findings are well established in scholarly work. By design, the experiment did not ask the systems trick questions. It simply asked them to show what they “knew” about a famous extinct human group, then checked that against the scientific record.

What the AI got wrong about prehistoric life

When the researchers looked at the generated images, they saw a pattern of errors that would jump out to any archaeologist. In many cases, the AI placed Neanderthals in scenes with technology that did not exist in their time, including ladders, metal objects and glass containers, details that were documented in the Feb analysis shared on Facebook. Some images showed Neanderthals with polished metal tools or in front of modern‑style shelters, visual cues that quietly pull viewers away from the actual archaeological record.

Text outputs were not much better. The project, described as Study Finds Generative, found that descriptions often repeated old tropes about Neanderthals being less intelligent and less social than Homo sapiens, even though recent work points to complex behavior and symbolic activity. In some prompts, inaccuracies rose above 80 percent of key factual claims, a rate that would be unacceptable in any textbook or museum label but that can slip by in a chatbot conversation because the prose sounds smooth and confident.

Old stereotypes in, old stereotypes out

The visual mistakes reflect a deeper problem with how these systems are trained. Generative models learn from huge collections of online images and text, which means they soak up decades of outdated Neanderthal art and writing. As a result, they recycle the same shaggy, hunched figures that dominated mid‑20th century museum dioramas, even though current reconstructions show a much closer resemblance to modern humans, a gap highlighted in coverage of outdated and inaccurate depictions. Looking at these AI images does not reveal a neutral view of the past; it reveals a mirror of old textbooks and movie posters.

Researchers quoted in the Feb reporting on how Neanderthals highlight the generative AI knowledge gap argue that this is not a minor detail. If AI tools keep repeating these images, they help freeze public understanding at an earlier stage of science. That feedback loop matters because teachers, students and even journalists now grab AI images and summaries for slides, explainers and background reading. The more that happens, the harder it becomes for updated research to dislodge the old picture.

Why this matters for classrooms and public trust

The team behind the Neanderthal work is blunt about the stakes for education. Their findings, summarized in a section called Practical Implications of, argue that teachers should treat generative AI as a starting point at best. They recommend that students learn to cross‑check AI answers about history and science against primary sources or curated databases, rather than copying chatbot text into essays or using AI art to stand in for real reconstructions. This amounts to a call for digital literacy that treats AI outputs as claims to be tested, not facts to be trusted.

The same reporting, in a section labeled Why This Matters, links the Neanderthal case to broader public trust in information. Generative AI is changing how images, writing and sound are created and shared, which means errors do not stay in one classroom or one social feed. They spread into news graphics, museum exhibits and policy debates. When people see polished AI content about topics like climate change, vaccines or elections, they may assume the same level of authority that they once reserved for an encyclopedia. The Neanderthal study suggests that this confidence is not earned.

Closing the gap between AI output and real scholarship

The University of Maine project also points toward ways to improve both the tools and how we use them. One recommendation is to connect generative systems more directly to curated scholarly sources, such as the scholarly knowledge bases that archaeologists already use. Instead of relying only on scraped web data, models could be tuned on vetted datasets for sensitive domains like human evolution, Indigenous history or medical guidance. This is a technical fix that still depends on social choices about who controls those datasets and how often they are updated.

At the same time, the researchers stress that users need better habits, not just better models. In coverage of What comes next, they suggest teaching students to approach generative AI cautiously and critically, so they learn to spot when a confident answer might hide a factual gap. Commentary on Generative AI in this context argues that a more critical society will be better equipped to handle the flood of synthetic media. Neanderthals are only the start: if we do not fix how we build and use these tools, the same hidden gaps will show up wherever the data is thin, the science has moved on, or the stakes are much higher than a cave painting.