NASA’s Curiosity rover has photographed a delicate Martian rock that looks strikingly like a piece of ocean coral, a visual jolt that collapses the distance between Earth’s reefs and the barren Red Planet. The intricate structure is tiny, but it carries outsized scientific weight, hinting at ancient water and complex chemistry that once shaped Gale Crater. I see in this latest image not proof of life, but a vivid reminder that Mars has a far more dynamic geological past than its rust-red surface suggests.

The coral-like rock is the newest in a growing gallery of strange formations Curiosity has cataloged over more than a decade of exploration. Each one, from branching “flowers” to twisted spires, is a frozen record of how minerals and water interacted billions of years ago, and together they are slowly tightening the case that Mars was once capable of supporting life.

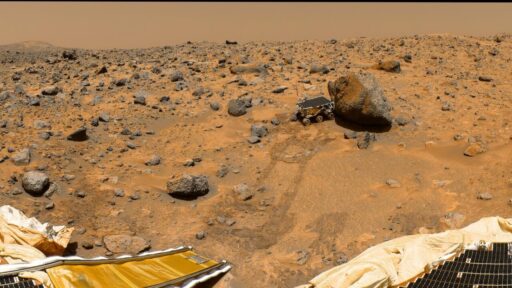

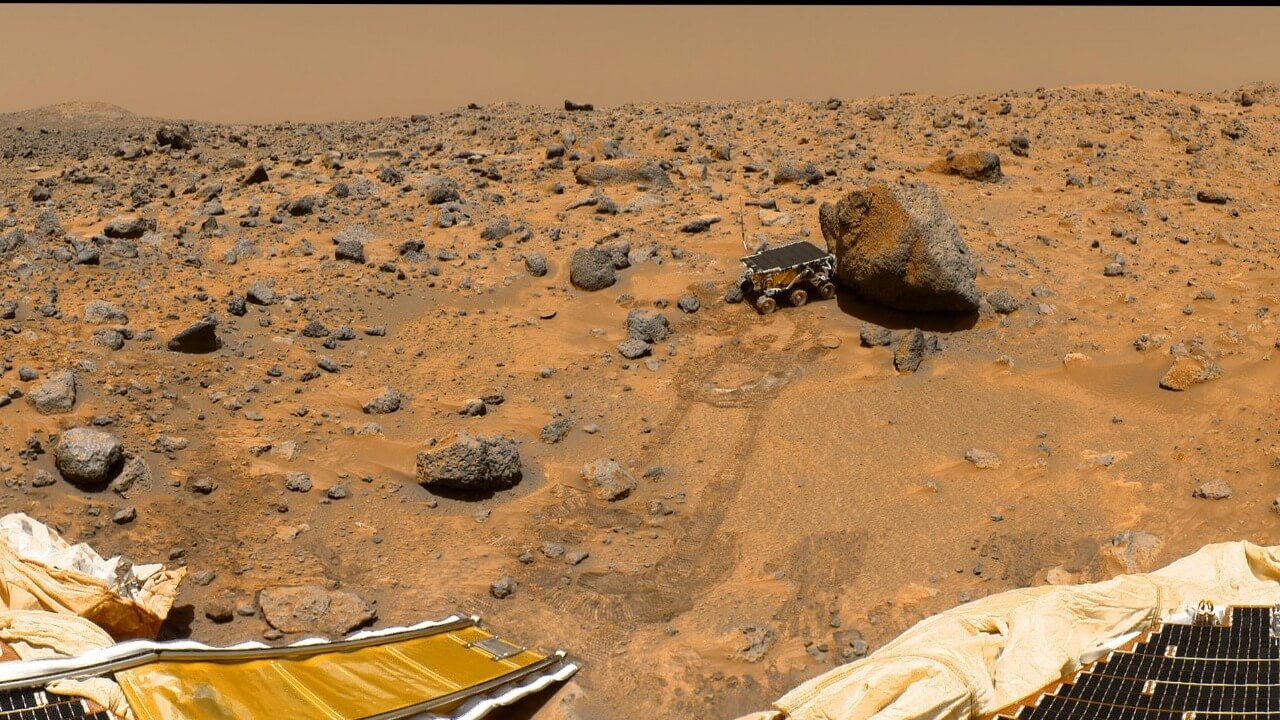

What Curiosity actually saw on the Martian surface

The latest image shows a knobbly, branching rock, only about an inch across, perched on the dusty floor of Gale Crater and shaped uncannily like a fragment of reef. Curiosity captured the scene with its mast-mounted camera, then zoomed in using its ChemCam system to reveal a lattice of thin, intertwined ridges that resemble the skeleton of coral on Earth. The feature sits among more ordinary stones, but its intricate texture stands out so sharply that mission scientists highlighted the view in a dedicated image release.

Close-up views from Curiosity’s laser-equipped camera show that the object is not a single smooth piece, but a cluster of thin mineral fins that have resisted erosion better than the softer rock around them. The rover has seen similar branching textures before, and the team now recognizes them as part of a broader family of “coral-shaped” rocks that dot parts of the crater. A separate ChemCam portrait of another example, captured at a different site, shows the same kind of delicate, branching framework, reinforcing that this is a recurring style of Martian rock rather than a one-off oddity, as seen in a later ChemCam view.

Why scientists say it is not literal coral

Despite the visual resemblance, researchers are clear that this Martian rock is not coral in the biological sense. Coral on Earth is built by living animals that secrete calcium carbonate skeletons in warm, shallow seas, and there is no evidence that such ecosystems ever existed on Mars. Instead, Curiosity’s team interprets the branching structure as a purely mineral formation, likely created when water once flowed through cracks in the bedrock, depositing harder material that later resisted erosion. That interpretation is consistent with earlier analyses of similar features, which show they are made of minerals like sulfates that precipitate from water, as described in mission updates on coral-shaped rocks.

Curiosity has, in fact, been finding these kinds of formations for years, and each time the scientific explanation has pointed to geology rather than biology. Earlier in the mission, the rover imaged a tiny “mineral flower” that showed the same sort of radiating, petal-like branches, and follow-up work identified it as a concretion formed by mineral-rich water moving through sedimentary layers. That earlier discovery, documented in detailed views of a tiny flower and later explained as a relic of ancient groundwater, set the template for how scientists now view the coral-like rock: as a beautiful, but non-living, record of water-driven mineral growth.

Clues to a wetter, more habitable Mars

Even if the coral look-alike is not a fossil, it still matters because of what it says about Mars’ past environment. To grow such intricate mineral structures, you need water moving slowly through rock, dissolving some ingredients and leaving others behind, often over long periods. That is exactly the kind of process Curiosity was sent to Gale Crater to document, and the rover has now assembled a body of evidence that the crater once hosted lakes, streams, and groundwater systems capable of sustaining habitable conditions. The new coral-shaped rock fits neatly into that picture, reinforcing earlier findings that Mars’ surface was shaped by persistent water activity, a point underscored in analyses of Gale Crater rocks.

Some reports have gone further, suggesting that the coral-like formations could be multi-billion-year-old structures that formed when Mars still had abundant surface water. Those accounts describe the rocks as about an inch across and note that their intricate branching hints at stable conditions over long timescales, which would have been friendlier to microbial life than the harsh, dry planet we see today. While scientists stop short of calling them fossils, they do treat them as signposts pointing back to a time when Mars’ climate was wetter and potentially capable of supporting life, a theme echoed in coverage of multi-billion-year-old Martian “coral.”

A growing family of coral-shaped rocks and “flowers”

The new image is not an isolated curiosity, but part of a pattern that has emerged as Curiosity climbs the layered slopes of Mount Sharp. Over time, the rover has photographed multiple rocks with branching, reef-like textures, including one nicknamed “Paposo” that drew attention for its especially intricate shape. Mission scientists have described these as “coral-shaped” rocks, noting that they are sculpted by a combination of mineral growth and relentless sandblasting by Martian winds. That combination of processes, captured in a series of coral-shaped finds, has left behind a surprising variety of delicate rock sculptures.

Earlier, Curiosity’s cameras also documented a tiny, branching rock that quickly became known as a “flower” because of its resemblance to a dried blossom. That object, only a few millimeters wide, was studied in detail and identified as a concretion formed when minerals precipitated from groundwater, a story laid out in explanations of the Martian rock and in follow-up coverage of the mineral flower. Together with the coral-like formations, these features show that Mars can produce intricate, almost organic-looking shapes purely through the interplay of water, minerals, and erosion.

From mission milestone to viral fascination

The timing of the coral-like discovery has added to its impact. Curiosity recently marked its thirteenth year on Mars, a milestone that has seen the rover transition from a fresh explorer to a veteran field geologist that occasionally needs “naps” to manage its power and hardware. Around that anniversary, mission updates highlighted both the rover’s longevity and its latest finds, including the coral-shaped rocks that have captured public imagination, as described in retrospectives on Curiosity’s thirteen years on the Red Planet.

Images of the coral-like rock quickly spread beyond official channels, circulating on social media pages devoted to space imagery and sparking debates about what they might mean. Posts in enthusiast groups highlighted the uncanny resemblance to ocean reefs, sometimes blurring the line between scientific description and speculation, as seen in shared group posts. Local broadcasters and online outlets amplified the story with headlines about “coral on Mars,” sometimes pairing the new images with earlier shots of unusual rocks that Curiosity had already cataloged, such as those featured in a broadcast post.