China is no longer content to treat space as a prestige project. It is rapidly knitting together asteroid probes, lunar infrastructure and robotic mining tools into a coherent industrial strategy that aims to turn off-world resources into real economic power. The race to commercialize space minerals is still in its early laps, but the country’s latest breakthroughs suggest it intends to set the pace.

From experimental robots that can walk and drill on alien terrain to ambitious sample return missions, the emerging picture is of a state that sees space mining not as science fiction but as a near-term extension of its manufacturing base. I see a clear throughline: China is building the hardware, the launch capacity and the partnerships it needs to dominate the supply chains of a future space economy.

From asteroid probes to industrial strategy

China’s most visible leap toward space mining is its Tianwen series of deep space probes, which are explicitly designed to interact with small bodies rather than just fly past them. The country has already committed to sending the Tianwen‑2 spacecraft to a near‑Earth asteroid, a mission that will test the precision navigation, anchoring and sampling techniques any future miner will need. Earlier planning details show that China expects Tianwen‑2 to capture material and help pave the way for further exploration in the 2030s, turning a one‑off science flight into a stepping stone for resource extraction.

The mission profile is deliberately aggressive. According to earlier descriptions, Tianwen‑2 is set to rendezvous with an asteroid, collect rocks and then shoot a capsule packed with samples back to Earth for a landing in a designated recovery zone. That kind of round‑trip choreography is exactly what a commercial operator would need to deliver ore from deep space to terrestrial refineries. When I look at how China has framed its broader space program, it is hard to see Tianwen‑2 as an isolated science mission; it is a rehearsal for a logistics chain that could eventually move metals instead of just data.

Robots built for alien mines

Hardware on the ground, or rather on the regolith, is where the country’s space mining ambitions become tangible. Engineers have unveiled a walking robot with multiple clawed legs that can both traverse rough terrain and drill into it, a design that directly anticipates the challenges of operating on asteroids and the Moon. In technical briefings, they note that each clawed leg can generate significant force while the robot runs on electricity, and that researchers are already exploring ways to extract and convert materials on‑site so the energy produced can power the system itself, a concept detailed in Jan reports.

The same research push highlights a new generation of mobility platforms that can move faster on smoother terrain while still gripping loose surfaces, a capability that was flagged in an Updated technical summary marked “01.29 22:38 GMT+8,” where the notation “01.29” and “38 G” appear in the timing details. I read those incremental gains in traction and power management as more than lab curiosities. They are the building blocks of autonomous excavators that could one day strip mine a crater rim or burrow into an asteroid, operating far from human supervision but tightly integrated into a supply chain that starts in orbit and ends in a factory.

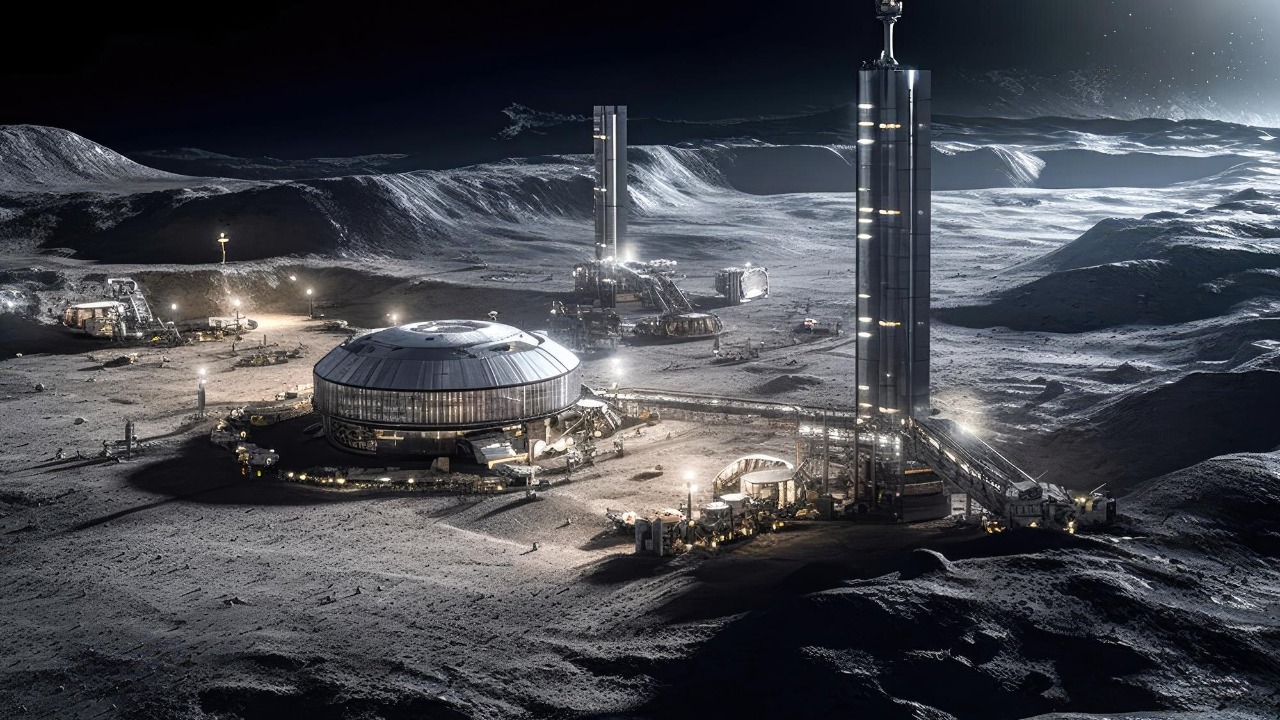

Lunar bases and the race for in‑situ resources

Asteroids are only half the story. China is also positioning the Moon as a long‑term industrial outpost, with plans to build a fully operational base equipped with an autonomous nuclear reactor by as early as 2035. Analysts have warned that China could overtake the United States as the top nation in space within five to ten years, and the lunar base concept is central to that projection. A reactor‑powered settlement would not just host astronauts, it would anchor a permanent presence for processing regolith, extracting oxygen and metals, and supporting outbound missions to richer targets.

The near‑term lunar manifest already reflects that industrial logic. One of the biggest missions of the year is expected to be the robotic Chang’e‑7 probe, which is set to explore the Moon’s south pole in the second half of the year, scouting for ice and volatile deposits that could be turned into fuel and life support. Cargo flights like Tianzhou‑10 to the Tiangong space station, described in Jack C.’s overview of recent activity, are part of the same logistics mindset. They normalize high‑cadence resupply and test reusable rockets, both of which will be essential if lunar mining is to scale beyond demonstration projects.

Private players, partnerships and a “space gold rush” mindset

State‑backed missions are only one pillar of this strategy. Beijing has also opened the door to a growing private launch and exploration sector, with firms like LandSpace’s Zhuqu rockets and startups focused on orbital services. In one profile, a young engineer describes how China has “entered a great space age,” contrasting their childhood watching American movies about space with the reality of now working in a domestic launch company. That cultural shift matters. It signals a pipeline of talent and capital that can take the technologies proven by national programs and adapt them into commercial services, from prospecting satellites to in‑orbit processing.

International partnerships are quietly reinforcing that trend. Recent cooperation between China and Algeria on a new satellite, developed by the China Academy of and launched from the Jiuquan spaceport, shows how Beijing is using joint missions to extend its technical standards and orbital infrastructure. At the same time, Chinese scientists are openly talking about a coming “space gold rush,” having identified 122 economically suitable asteroids for mining when both technical feasibility and cost are taken into account. That figure, cited in a Sep analysis that begins with the word “Taking,” underscores how far planning has moved beyond vague aspiration into detailed target lists.

Economic stakes and geopolitical ripple effects

The economic logic behind this push is straightforward. Asteroid metal mining promises access to platinum‑group metals, nickel and cobalt in concentrations that could reshape global markets by 2040, a prospect outlined in a technical explainer titled Understanding Asteroid Metal. That analysis walks through how extracting and processing ore in microgravity could eventually undercut terrestrial mining costs, especially if fuel and basic materials are sourced off‑world. When I map those projections onto China’s broader industrial policy, the appeal is obvious: secure long‑term supplies of critical minerals, reduce vulnerability to maritime chokepoints and environmental constraints, and potentially export refined space‑sourced materials to the rest of the world.

There is also a clear geopolitical dimension. A recent overview of Asia’s emerging space manufacturing ecosystem notes that They are focused on extracting lunar ice to turn into hydrogen fuel and drinking water, and that Over in China, a company called Origin Space is sending out robotic rovers with elemental detection tools. Those capabilities, combined with national programs like the Long March launchers that carried China’s asteroid probe, could give Beijing a first‑mover advantage in setting norms for resource claims and safety zones. Even popular explainers about the country’s 2026 Moon plans, such as a video where a host named Jan discusses how the mission might surprise viewers and mentions that the Chi narrative is shifting, reflect a growing awareness that whoever masters off‑world mining will wield new forms of influence.

For now, the legal and diplomatic frameworks around space resources remain unsettled, and many of the most ambitious timelines are aspirational. Yet when I line up the data points, from Jan assessments that 2025 was China’s busiest year in space to Jan reports on experimental mining robots, the trajectory is unmistakable. Beijing is racing ahead not just to plant flags, but to build the machinery, infrastructure and legal arguments that could turn the Moon and nearby asteroids into extensions of its industrial heartland. The rest of the world is only beginning to grapple with what that will mean for markets, alliances and the balance of power in the decades to come.