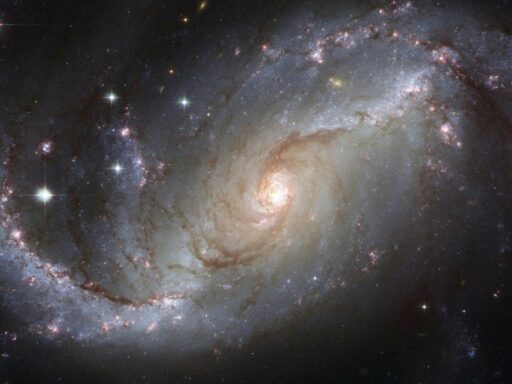

A violent smashup between two young worlds has been caught almost in the act just 25 light-years from Earth, giving astronomers their first direct look at a planetary collision in another solar system. The impact unfolded around the bright star Fomalhaut, where a mysterious object once thought to be an exoplanet has now been unmasked as the dusty wreckage of colliding asteroids or planetesimals. For anyone trying to understand how planets grow, shatter, and rebuild, this nearby cosmic crash is a rare natural experiment playing out on our doorstep.

The event turns a long standing puzzle into a vivid story of destruction and renewal. What looked like a single “planet” has instead revealed itself as at least two separate debris clouds, each the aftermath of a catastrophic impact in a young system still rich with dust and ice. I see this as a turning point in how we picture the chaotic adolescence of planetary systems, including our own.

From “missing planet” to colliding worlds at Fomalhaut

For years, astronomers tracked a bright speck dubbed Fomalhaut b, an apparent exoplanet candidate orbiting the star Fomalhaut inside a broad system of dusty belts. That point of light gradually faded and then vanished, prompting a fresh look with new Hubble Space Telescope images that show the object was never a stable world at all but a transient cloud of debris expanding along its orbit. The latest analysis ties that fading glow to a violent collision between two large bodies in the inner region of the Fomalhaut system, where a compact source orbits inside a wider ring of dust and debris that encircles the star.

In the new data, astronomers do not just see one cloud, they see evidence for multiple impacts. One bright, compact feature appears in recent images where nothing was visible in earlier Hubble frames, a sign that a fresh collision has produced a new spray of dust near Fomalhaut. The emerging picture is that at least two asteroids or planetesimals have crashed in quick succession, creating overlapping clouds that mimic the appearance of a planet and then disperse. That interpretation is strengthened by detailed modeling of the dusty belts around Fomalhaut, which show how collisions among embedded bodies can feed the system’s broad ring of debris while also generating short lived, planet like blobs of light.

The nearby nature of this system makes the discovery even more striking. Fomalhaut sits only about 25 light-years away, close enough that Hubble can resolve fine structure in its debris belts and track changes over time. In one set of observations, the telescope effectively watched a new dust cloud switch on where none had been seen before, a “now you see it, now you do not” sequence that is hard to reconcile with a solid planet but fits perfectly with a fresh impact between two asteroids. Visualizations of the event show two rocky bodies smashing together and spraying out a fan of dust that gradually stretches into a long, faint trail along the orbit.

A once in 100,000 years view of planetary chaos

What makes this detection historic is not only the proximity of Fomalhaut but the timing. Theory dictates that you should not see these collisions except once every 100,000 years or rarer, yet Hubble appears to have caught at least one such event in real time and possibly two in the same system. That mismatch between expectation and observation suggests either that astronomers have been unusually lucky or that the inner regions of Fomalhaut are far more collision rich than standard models predict. If the latter is true, the system may be in a particularly active phase of planet building and planet breaking, with large bodies frequently grinding themselves down into dust.

By observing these impacts almost in real time, scientists can estimate how often these kinds of crashes happen, how massive the colliding objects must be, and how quickly the resulting dust clouds expand and fade. The debris plumes around Fomalhaut are bright enough that they can be tracked across multiple Hubble orbits, letting researchers watch the clouds stretch and thin as they move through the star’s complex system of dusty debris belts. That evolving shape encodes the size of the fragments, the speed of the impact, and the gravitational pull of any unseen bodies that might be shepherding the dust.

The new images also help resolve the long running mystery of the disappearing exoplanet candidate. Earlier observations had hinted that Fomalhaut b was fading faster than a normal planet could, and the latest data confirm that the object is better explained as a dust cloud that has now dispersed below Hubble’s detection threshold. In effect, the telescope has watched a supposed world dissolve into powder, revealing the underlying physics of a catastrophic collision rather than the steady glow of a stable planet. That insight reshapes how I think about other ambiguous exoplanet candidates, especially those seen only once or twice at the edge of detection.

What Fomalhaut’s crash tells us about our own solar system

For planetary scientists, the Fomalhaut collisions are a rare chance to test ideas about how young systems evolve by comparing them to a nearby, high resolution example. Astronomers have long suspected that the early solar system went through a similar era of violent impacts, including the giant collision thought to have formed Earth’s Moon and the bombardment that scarred the surfaces of Mars and Mercury. Seeing two asteroids crash around a nearby star, with the dusty aftermath still visible, is like looking back in time at the kind of events that once shaped our own planets. The fireworks around Fomalhaut show that such collisions are not just theoretical relics but ongoing processes in young systems.

The discovery also sets the stage for follow up work with newer observatories. Kalas has been awarded time over the next three years to use the James Webb Space Telescope’s Near Infrared Camera to probe the dusty aftermath in more detail, searching for warm fragments, hidden planets, and subtle structures in the belts that Hubble cannot see. Combining Webb’s infrared sensitivity with Hubble’s long time baseline will let researchers trace how the debris clouds cool, clump, and disperse, turning a single snapshot of destruction into a full timeline of planetary scale change. I expect that sequence to become a benchmark for interpreting other debris rich systems and for refining models of how often worlds collide as they grow.

There is also a practical lesson for exoplanet hunters. The spectacular, resulting dust cloud around Fomalhaut mimics the appearance of a planet so closely that it fooled observers for years, a reminder that not every point of light near a star is a stable world. As more powerful telescopes come online and push deeper into crowded, dusty systems, astronomers will need to distinguish between true planets and short lived debris clouds that only masquerade as them. The nearby crash at Fomalhaut, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope and analyzed by teams working with NASA, ESA, STScI, and others, turns that challenge into an opportunity, offering a template for how to read the subtle signatures of cosmic collisions in the glow of distant starlight.

In that sense, the first direct images of collisions in a nearby star system are not just a curiosity, they are a new kind of laboratory. By tying together the fading of Fomalhaut b, the sudden appearance of fresh dust, and the structure of the surrounding belts, astronomers have turned a puzzling “planet” into a detailed case study of planetary demolition and renewal. I see that as the real breakthrough: a single nearby star, only 25 light-years away, now anchors our understanding of how often worlds crash, how they leave their mark on the dust around them, and how easily their wreckage can masquerade as something far more permanent.

Unverified based on available sources.

To appreciate the full scope of this work, it helps to trace how multiple teams and instruments converged on the same story. Early hints of a collision came from careful analysis of Hubble images that showed the supposed planet changing brightness and shape in ways a solid body could not sustain. Follow up observations captured a new compact source near Fomalhaut that had been absent before, while independent modeling of the system’s dusty belts predicted that such impacts should occasionally produce bright, short lived clouds. Together, these strands of evidence have transformed a once controversial exoplanet candidate into the clearest view yet of a planetary collision unfolding in another solar system.

As I weigh the implications, I keep coming back to the odds. If theory says we should only see such an event once every 100,000 years, yet we have already caught one, perhaps two, in a single nearby system, then either Fomalhaut is unusually chaotic or our expectations about collision rates need to be revised. Either way, the system has become a touchstone for future work, a place where telescopes like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope can watch the messy, creative violence of planet formation play out in real time, only 25 light-years from home.

Looking ahead, I expect Fomalhaut to remain a priority target for years. With each new image, astronomers will refine their understanding of how dust, ice, and rock interact in the aftermath of a giant impact, and how those interactions sculpt the belts and gaps that we see around many young stars. The cosmic collision spotted so close to Earth is more than a spectacular snapshot, it is the opening frame of a long running movie about how planetary systems live, die, and begin again.

As the data accumulate, the story of Fomalhaut will likely ripple outward, reshaping how we interpret debris disks, exoplanet candidates, and the early history of our own solar system. For now, though, the key point is simple. A nearby star has given us front row seats to a kind of event that theory once consigned to the distant past and to vanishingly small odds. Thanks to the sharp eyes of Hubble and the persistence of astronomers who refused to accept an easy answer, we can now watch the dusty aftermath of colliding worlds unfold in exquisite detail, a reminder that even in a mature galaxy, planetary systems are still works in progress.

In the end, the first of its kind collision seen just 25 light-years away is both a scientific milestone and a humbling spectacle. It shows that the forces that once shaped Earth and its neighbors are still at work nearby, grinding some worlds to dust even as others coalesce. For anyone who has ever looked up at the night sky and wondered how planets are made, Fomalhaut now offers a rare, vivid answer, written in the expanding cloud of a shattered world.