Scientists are increasingly warning that the modern diet of grab‑and‑go snacks and heat‑and‑eat dinners is not just expanding waistlines, it is eroding the very mental brakes that help people resist temptation. A growing body of research now links popular convenience foods to measurable losses in self control, from moment‑to‑moment food choices to longer term cognitive decline. I see a clear pattern emerging: the more our meals are engineered in factories, the harder it becomes for our brains to say no.

That pattern matters far beyond the supermarket aisle. Self control underpins everything from sticking to a budget to staying focused at work, and the same neural circuits that decide between an apple and a doughnut also help us weigh risks, delay gratification, and plan ahead. When those circuits are constantly bathed in sugar, fat, and ultra‑processed additives, the evidence suggests they start to misfire in ways that make everyday discipline feel like an uphill climb.

New evidence that convenience foods blunt cognitive control

The latest warning sign comes from New research that directly ties frequent consumption of popular ultra‑processed convenience foods to a measurable loss of cognitive control. In that work, people who regularly relied on packaged snacks, frozen meals, and similar products showed a significant decline in mental wellbeing and in the brain’s ability to regulate impulses. I read that as a shift from “I choose this” to “this happens to me,” where the food environment starts to dictate behavior more than conscious intention does.

The same pattern appears when scientists zoom out from day‑to‑day choices to longer term brain health. A large Study of adults found that those eating the highest levels of ultraprocessed foods experienced faster cognitive decline than peers who ate less, even after accounting for overall diet quality. A related analysis highlighted that people who combined lower intake of these products with a brain‑focused pattern such as the MIND diet preserved memory and executive function more effectively. To me, that combination of short term control problems and long term decline paints a stark picture of what is at stake when convenience becomes the default.

How sugar, fat and additives hijack the brain’s reward system

To understand why these foods are so hard to resist, it helps to look at how they interact with the brain’s reward circuitry. Research shows that the brain begins responding to fatty and sugary foods even before they touch the tongue, with Research indicating that merely seeing a dessert can activate dopamine‑rich regions in the brain’s reward circuit. A follow‑up report notes that Merely pairing sugar and fat in specific ratios produces especially strong responses, which food manufacturers can exploit when formulating snacks and ready meals.

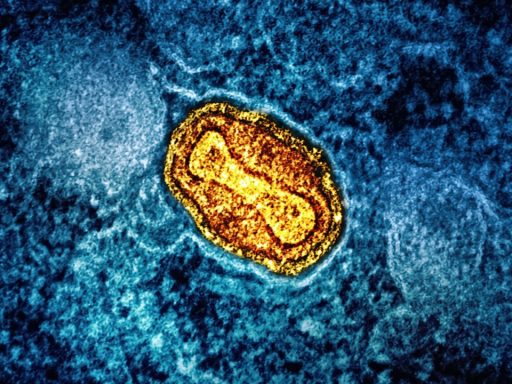

Neuroscientists reviewing high‑fat, high‑sugar diets describe a cascade of changes that look strikingly similar to what happens with addictive substances. According to an Abstract that synthesizes functional neuroimaging work, repeated exposure to high‑fat, high‑sugar (HFHS) foods alters signaling in regions that govern reward, learning, and inhibition. The Purpose of Review is to map how HFHS patterns contribute to eating disorders and food addiction, and the authors conclude that these diets can blunt sensitivity to natural rewards while making people more driven to seek out hyper‑palatable products. In practical terms, that means the more often I rely on convenience foods, the more my brain learns to crave them and the less satisfying ordinary meals may feel.

The brain regions that decide between “want” and “should”

Self control is not a vague personality trait, it is a set of identifiable brain processes that can be strengthened or undermined. Work using functional MRI has shown that everyone draws on the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, or vmPFC, when making value‑based choices, but that people who successfully resist unhealthy foods recruit additional control regions. One experiment, described in a What researchers found, asked people to choose between tasty but unhealthy items and healthier options while their brains were scanned. When participants were cued to think about health, the balance of activity in vmPFC shifted in favor of nutritious foods.

A companion study from the same group, summarized in a report that notes When people focused on healthiness, found that subjects were less likely to eat unhealthy foods whether or not they rated them as tasty. Another line of work, highlighted in a piece on the difference between people with strong and weak self control, points to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex as a key regulator. A related experiment on dietary choice and obesity, which emphasizes the role of the DLPFC, suggests that engaging this region more effectively could help people with poor self control make healthier decisions.

From junk food cravings to everyday impulse problems

What starts as a tug‑of‑war over chips and cookies can spill into other parts of life. Reporting on brain imaging work has described how News about two key brain areas shows that one region tracks the taste of a food while another weighs longer term goals, and that the strength of communication between these regions predicts who can resist junk food. In that account, FRIDAY coverage emphasized that Two areas of the brain work together to give some people more willpower than others. If ultra‑processed foods repeatedly tip that balance toward immediate taste, it is reasonable to worry that the same bias could affect decisions about spending, screen time, or substance use.

Psychologists who study eating behavior argue that the design of these products is not accidental. One analysis of mental health and diet notes that Key features of ultra‑processed foods are engineered to exploit natural cravings, creating addiction‑like behavior. The same piece explains that Ultra products can disrupt neurotransmitter balance and contribute to low‑grade inflammation, while Diets high in these items are associated with mood disturbances and impaired concentration. When I connect those dots with the imaging work on reward and control circuits, it becomes hard to see junk food cravings as a trivial, isolated problem.

Why vulnerable brains may pay the highest price

The risks are not evenly distributed. A comprehensive review of nutrition and brain health reports that Jun findings link poor maternal nutrition, including high UPF consumption, to hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, and altered neurodevelopment in offspring. The same paper stresses that Poor diet in adolescence, another critical stage of brain maturation, can shape long term cognitive and emotional outcomes, and that high UPF intake is especially concerning for women, children, and adolescents. When I consider how aggressively convenience foods are marketed to exactly these groups, the public health implications become hard to ignore.

Those concerns intersect with the broader evidence on cognitive decline and self control. The Apr report on ultraprocessed foods and cognition underscores that those eating the highest levels of these products had steeper declines in memory and executive function, while a separate Study highlights that combining lower UPF intake with a MIND‑style pattern may offer protection. When I put that alongside the New findings on measurable loss of cognitive control, the message is blunt: the convenience foods that saturate modern life are not just a neutral backdrop, they are active players in shaping how well our brains can steer our behavior.