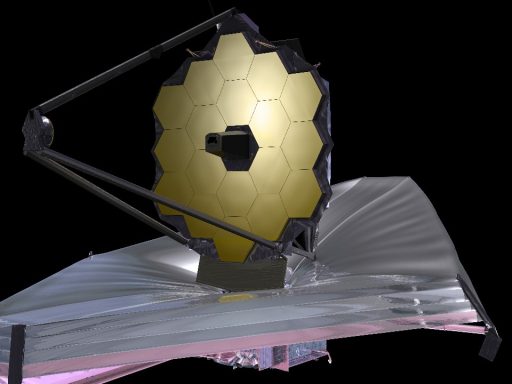

Artemis II is tantalizingly close to flight, with its crewed loop around the Moon framed as the moment the United States resumes deep space journeys last seen in the Apollo era. Yet even as the rocket and capsule inch toward the pad, the mission cannot simply light the engines and go, because every step between the Vehicle Assembly Building and splashdown has to prove, in sequence, that four astronauts can leave Earth, swing past the Moon and return alive.

From the outside, the delays and rehearsals can look like bureaucracy or caution bordering on paralysis. I see something different: a system methodically testing each link in a fragile chain, from the Space Launch System booster to the Orion capsule’s heat shield, before anyone commits to a launch window that stretches from early February into April and beyond.

The long road from rollout to “go” for launch

The first reason Artemis II cannot depart immediately is that the rocket and spacecraft still have to complete a tightly choreographed series of ground tests. At the end of January, At the Kennedy Space Center, NASA plans a full “wet dress rehearsal,” loading the Space Launch System with cryogenic propellants and running the countdown into the final minutes to verify that valves, sensors and software behave as they must on launch day. Only after this high pressure fueling test, which mimics the most dangerous parts of the countdown, can managers judge whether the rocket is truly ready to fly with people on board.

Even getting to that rehearsal is a campaign in itself. Then there is the rollout of the Space Launch System and the Orion capsule, scheduled for a Saturday in mid January, a slow crawl on the crawler-transporter that exposes the stacked vehicle to the coastal environment and checks its ability to withstand the vibrations and flexing of the journey to the pad. That Space Launch System rollout is followed by days of pad integration, when teams connect power, data and propellant lines and rehearse emergency egress for the crew. Once at the launch pad, technicians must hook up the cryogenic propellant systems and verify that ground equipment can load and drain fuel while keeping the crew safe, a process that Once the rocket is in place will take multiple shifts of work.

Why the schedule slipped to 2026

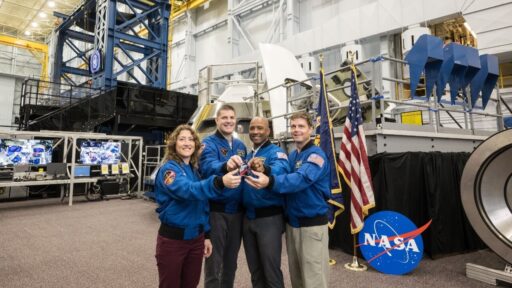

The second reason Artemis II is not launching immediately is that NASA is still digesting hard lessons from Artemis I, particularly around Orion’s heat shield. The Artemis II mission is designed to send four astronauts around the Moon as part of NASA’s plan to build a long term presence there, but that trajectory was pushed back to April 2026 after engineers saw unexpected charring and material loss on the uncrewed capsule’s thermal protection system. The agency formally delayed the crewed flight to study these heat shield issues and redesign parts of the hardware and flight profile.

NASA later explained that the delay was triggered by specific behavior inside Orion, where temperatures stayed within safe limits but gases trapped in the heat shield material led to more ablation and cracking than models had predicted. That finding, centered on Orion, forced a deeper look at how the capsule will handle the brutal reentry from lunar speeds. NASA engineers expected some charring as the spacecraft endured temperatures above 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius), but the pattern of damage on Artemis I raised questions about how the material might behave when four people are strapped inside, which is why NASA has been unwilling to rush.

Risk, reliability and the limits of a mega-rocket

Even with the hardware nearing the pad, the mission profile itself has been reshaped to keep risk within acceptable bounds. NASA revised the trajectory so that the Artemis 2 Orion will splash down in the Pacific Ocean closer to San Diego, a change intended to give recovery forces more options if anything goes wrong during reentry and to preserve as much schedule margin as possible for later missions in the Artemis campaign. In Artemis II, the main danger is not landing on the Moon but surviving the high speed return, when the capsule’s exterior can reach over 2,700 degrees Celsius, a thermal onslaught that has prompted public debate about the risks the four astronauts will face, including from voices like Isaacman.

There is also a structural reason Artemis II cannot simply be slotted into the calendar like a commercial launch. The Space Launch System is a bespoke heavy lifter built around a limited inventory of RS-25 engines and solid boosters, and there were only 16 RS-25 engines available from the shuttle era, each costing as much as $1 million per launch, which makes rapid fire cadence impossible for BFR-scale rockets like Starship or SLS. NASA has already delayed the next two Artemis missions to address the heat shield and other issues, underscoring that the program is still in a test phase where each flight is treated as a one off event rather than a routine service, a reality spelled out when NASA acknowledged the knock on effects for Artemis 3 and beyond.