Debate over how far the United States should go in restricting artificial intelligence hardware to China is shifting again. The top Democrat on the US House committee focused on China is now signaling that some Nvidia H200 chip sales could be acceptable, as long as they fit into a broader strategy that keeps the most advanced systems out of Chinese hands. That stance highlights a growing push in Washington to fine tune export controls instead of treating every new chip as an automatic security threat.

The argument is no longer about whether to limit cutting edge AI hardware, but about where to draw the line between economic interests and national security. Nvidia, Chinese AI firms, and US allies are all watching closely because the decision on H200 exports could shape how Washington handles the next wave of chips that follow.

The committee’s split over Nvidia and China

The House Select Committee on China has become a central stage for this fight, and its leaders are not fully aligned. The top Democrat has indicated that limited Nvidia H200 exports might be acceptable, while the Republican chair, John Moolenaar of Michigan, is pressing for a much tougher line on any advanced hardware that could help Chinese AI companies. Their disagreement reflects a wider split in Congress over how to balance control of key technology with the commercial pull of the Chinese market.

In a recent statement, the Michigan Republican warned that Chinese AI companies are training their systems with Nvidia products in ways that could threaten US interests and the security of Taiwan. Chairman John Moolenaar of the Select Committee on China has already written to Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, arguing that Nvidi hardware has been used by DeepSeek and the People’s Liberation Army, and calling for tighter controls. That pressure sets a high bar for any Democrat who wants to keep some export channels open.

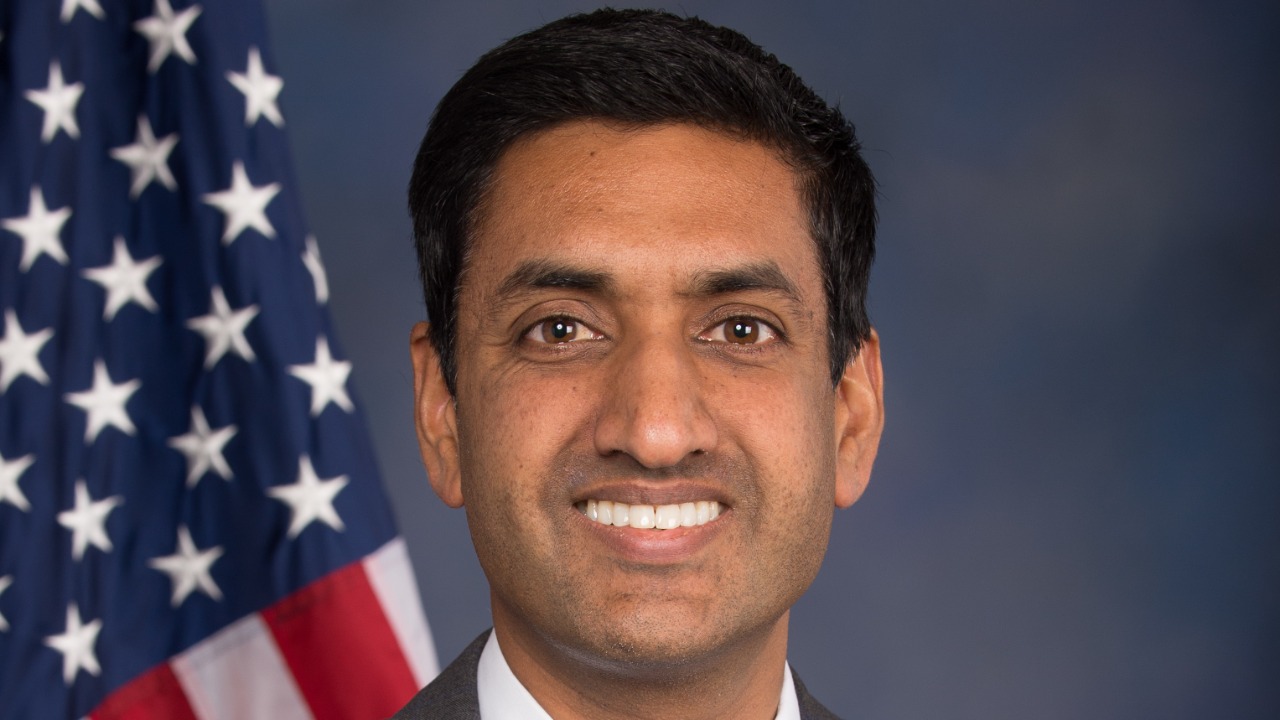

Ro Khanna’s conditional green light for H200

Against that backdrop, the committee’s senior Democrat, U.S. Representative Ro Khanna, is carving out a narrower position. He is open to allowing Nvidia H200 sales to China, but only as part of a framework that clearly blocks the next generation of chips. According to Feb reporting by Reuters, Khanna has signaled that the United States can permit exports of older chips while still protecting its technological edge, a stance that tries to keep both security hawks and industry on board.

He has been explicit about where he thinks the line should be drawn. He said, “We certainly should not be sending them Rubins. We should not be sending them Blackwells,” referring to Nvidia’s most advanced products, and added, “But after we have a two-year lead, we can sell them the older chips.” His use of “But” to frame that trade off shows how he is trying to separate current cutting edge designs from hardware that Washington views as one step behind. That quote, reported through Khanna’s comments, lays out a simple test: keep Rubins and Blackwells at home, but treat H200s more like legacy gear once newer chips are in the field.

Why the H200 sits in a gray zone

The Nvidia H200 itself sits at an awkward point in this policy debate. It was released in 2024 as part of Nvidia’s “Hopper” generation, which came before the current “Blackwell” line. That means it is no longer the company’s flagship, yet it still offers serious computing power for training large AI models. For policymakers, the H200 is not a museum piece, but it is not the newest weapon in the toolbox either, which is why it has become a test case for how to handle slightly older high performance chips.

Khanna’s argument hinges on that status. If Blackwell and future Rubins designs are seen as the true cutting edge, then the H200 can be framed as a step behind, suitable for controlled exports that generate revenue without handing China the latest breakthroughs. Reports describing the Hopper generation as the predecessor to Blackwell support that view. At the same time, critics point out that even one generation old hardware can still supercharge military and surveillance applications, which is why the chip’s place in the lineup does not settle the argument on its own.

Security warnings from Moolenaar and Krishnamoorthi

Republicans on the committee are not the only ones raising alarms. Ranking Member Krishnamoorthi has been pressing for strict limits on AI chip exports to China for more than a year, and his warnings go directly to the question of whether any advanced hardware, even downgraded versions, should be allowed to flow to the People’s Republic of China. His concern is that once hardware is inside the PRC, it is hard to control how it is used or who gains access.

Back in Aug, Ranking Member Krishnamoorthi warned that allowing even downgraded versions of cutting edge AI hardware to flow to the PRC risks eroding US leverage and the integrity of advanced technology controls. Then in Dec, he issued a statement titled Krishnamoorthi Raises Alarm as the Trump Administration Moves to Approve H200 AI Chip Exports to the Chinese Communist Party, arguing that such exports could help the CCP shape the future of AI in ways that run against US interests. Those statements show how some Democrats see H200 sales not as a compromise, but as a direct threat.

Economic stakes for Nvidia and US tech leadership

Behind the political fight sit large commercial stakes. Nvidia has built its business on selling high end accelerators to cloud providers, research labs, and AI startups worldwide, and China has been one of the biggest markets for that hardware. Tight export limits have already forced the company to design lower performance variants for Chinese customers, and any decision on H200 sales will affect how it manages that split between full strength products and restricted versions.

US policymakers are also weighing how export rules affect America’s own AI edge. If Nvidia is blocked from selling slightly older chips like the H200 abroad, it may look for other ways to recoup development costs, including higher prices at home or slower investment in new designs. Some in Washington argue that a carefully managed flow of previous generation hardware can help keep US firms strong while still preserving a clear lead in performance. Others counter that once chips are in Chinese data centers, they can be combined and scaled in ways that narrow the gap regardless of generation.