A new class of material is quietly rewriting what scientists thought was possible at the boundary between glass and plastic. By carefully arranging polymer chains into a finely tuned network, researchers have created a hybrid that can be molded like glass at high temperatures yet shrug off impacts like a tough plastic, a combination that long seemed out of reach.

The work, centered on a family of polymers known as “compleximers,” suggests that the old trade off between rigidity and resilience is no longer absolute. If this approach scales, everything from car bodies to phone screens could be built from transparent solids that bend, absorb energy, and snap back instead of shattering.

How compleximers bend the rules of glass and plastic

The starting point for this breakthrough is a deceptively simple question: can a solid be both glassy and impact resistant without relying on the usual chemical tricks of conventional plastics. Researchers at Wageningen University tackled that challenge by designing a “compleximer,” a polymer network whose internal structure behaves a bit like a molecular zipper, locking together at room temperature but loosening when heated so it can be reshaped. In their description, the material can be processed and formed at elevated temperatures in a way that resembles glass, yet it retains the toughness and ductility associated with high performance plastics, a balance that is documented in their work on a glass-like plastic.

In technical terms, the compleximer relies on a dense web of reversible physical attractions rather than permanent chemical crosslinks, which lets the material flow when heated but lock into a rigid state when cooled. J (Jasper) van der Gucht and colleagues at Wageningen Univ describe how this architecture allows the polymer to be molded and shaped at high temperatures while still delivering strong impact resistance once it cools, a combination that has typically required compromises in either stiffness or toughness. Their description of the compleximer concept underscores how carefully tuned molecular forces can deliver macroscopic properties that once seemed mutually exclusive.

The ‘impossible’ glass‑plastic hybrid and its physics

What makes this hybrid feel “impossible” is not just its performance, but the way it appears to defy long standing expectations in polymer physics. For decades, theory suggested that materials with glass like stiffness would inevitably become brittle, because the same dense packing that resists deformation also encourages cracks to race through the structure. Researchers working on this amber colored hybrid argue that by arranging the polymer chains into interlocking domains that behave like molecular magnets, they have effectively shattered this assumption and produced a solid that is both rigid and forgiving under stress, a claim detailed in reports on an “impossible” material.

The physics behind this behavior hinges on how those domains interact when the material is stressed. Instead of cracks propagating cleanly, the molecular magnets pull on each other, dissipating energy and allowing the structure to deform without catastrophic failure. Detailed explanations of this mechanism describe how one part of the network can slide and rearrange while another part holds the overall shape, a duality that lets the hybrid bend and then recover. In one account, the team notes that traditional molecular magnets rely on specific chemical bonds, while these compleximers use physical attractive forces to achieve a similar effect, a distinction highlighted in technical coverage of the molecular design.

A global race to make glass that will not shatter

The compleximer work slots into a broader international push to reinvent glass itself, turning a notoriously fragile material into something that can flex, absorb energy, and heal. In Japan, researchers have demonstrated shape memory glass that bends and reforms without breaking, a material that absorbs stress and returns to its original form instead of fracturing into sharp shards, a behavior described in reports on shape memory glass.

Germany based teams have taken a different route, using nanostructure engineering to create glass like materials that are stronger than steel yet capable of bending smoothly under load. One account describes how, unlike traditional glass which shatters under stress, this new material behaves almost like a sheet of transparent metal, flexing instead of cracking, a property highlighted in coverage of nanostructured glass. Other reports from Dresden describe a glass like metal that bends but never breaks, explicitly contrasting it with normal glass that fractures into dangerous shards and emphasizing how it stays safe in everyday use, as seen in descriptions of a glass like metal.

From lab curiosity to real‑world surfaces

For all their exotic physics, these materials will ultimately be judged on whether they can make everyday objects safer and longer lasting. Demonstrations from Japan describe flexible and unbreakable glass that absorbs stress and returns to its shape without cracking, with scientists explicitly framing it as a revolutionary way to make transparent surfaces that are flexible, resilient, and effectively unbreakable, a vision captured in reports on flexible glass. In Germany, similar concepts are being pitched as a way to end breakage in consumer products, with one account describing how businessmen see unbreakable flexible glass as a technology that could end breakage forever, a sentiment reflected in coverage of unbreakable glass.

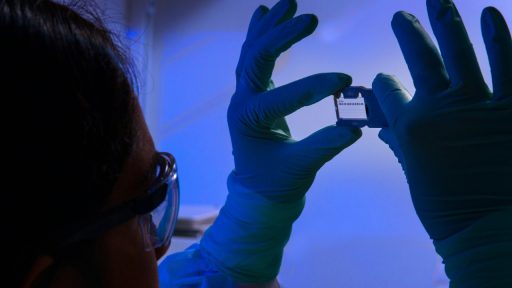

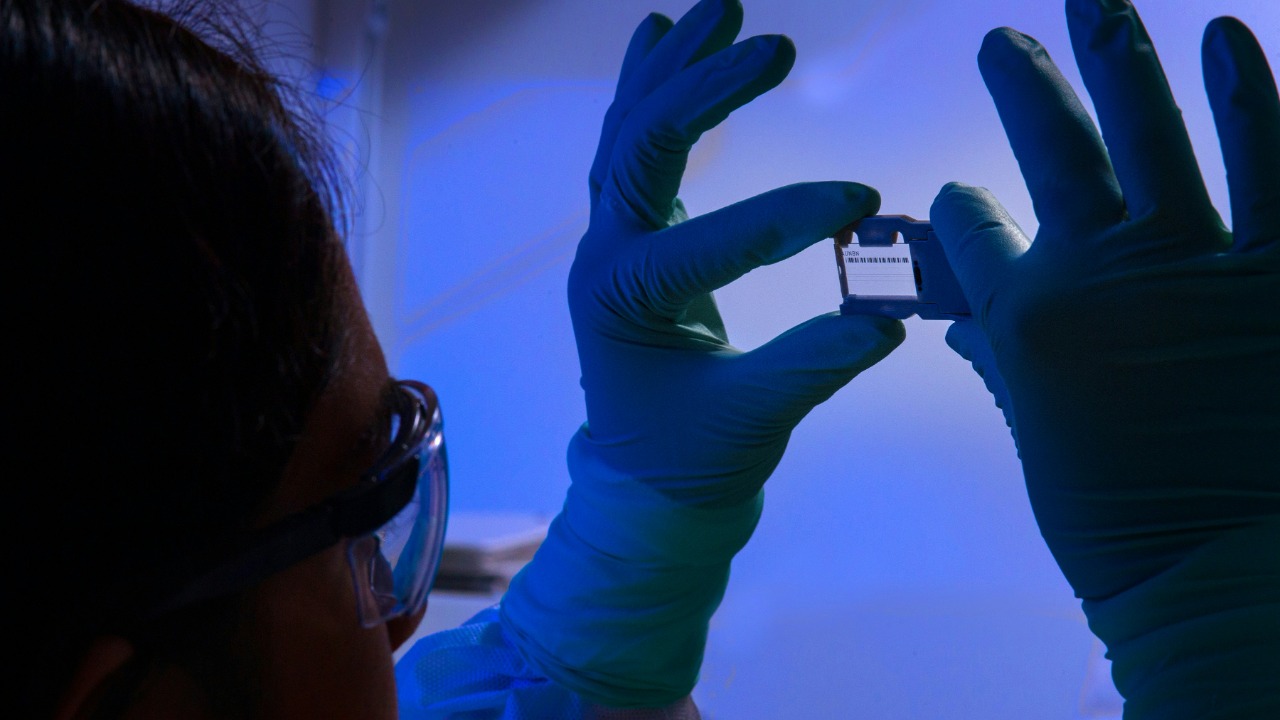

Laboratory demonstrations already hint at how such surfaces might look in practice. One report describes a materials science lab where new glass stronger than steel and lightweight is being developed, explicitly noting that unlike normal glass that fractures into sharp shards, this material absorbs stress and returns to its shape without cracking, and linking that behavior to the future of smart surfaces, as detailed in accounts of smart surfaces. Separate descriptions of Germany building a glass like metal that bends but never breaks in Dresden emphasize again that unlike normal glass that fractures into sharp shards, this material absorbs stress and returns to its shape without cracking, making it safer in everyday use, a point reinforced in coverage of bending glass metal.

Designing materials like living systems

What ties compleximers and flexible glass to a wider scientific trend is the idea that structure can matter more than composition. In metamaterials research, engineers have shown that unusual properties such as high compressive energy absorption and shape recovery can arise primarily from the arrangement of internal components rather than the base substance itself, a principle spelled out in work on textile inspired metamaterials. The compleximer’s molecular magnets and the nanostructured glass from Germany both fit this pattern, using architecture at the nano and microscale to redirect stress, dissipate energy, and recover shape.

Similar thinking is reshaping other fields, including biology inspired engineering. In immunology, for example, researchers have recently published a blueprint for designing T cells to kill more effectively, mapping how cellular circuits can be tuned to change behavior, work that involved co corresponding authors such as Chung, Susan M. Kaech, PhD, and Wei Wang, PhD at UC San Diego and was reported in Nature linked work. The common thread is that by treating molecules, cells, or structural elements as programmable building blocks, scientists can create systems that respond dynamically to stress, whether that means a T cell adapting to a tumor or a glass plastic hybrid flexing instead of breaking.