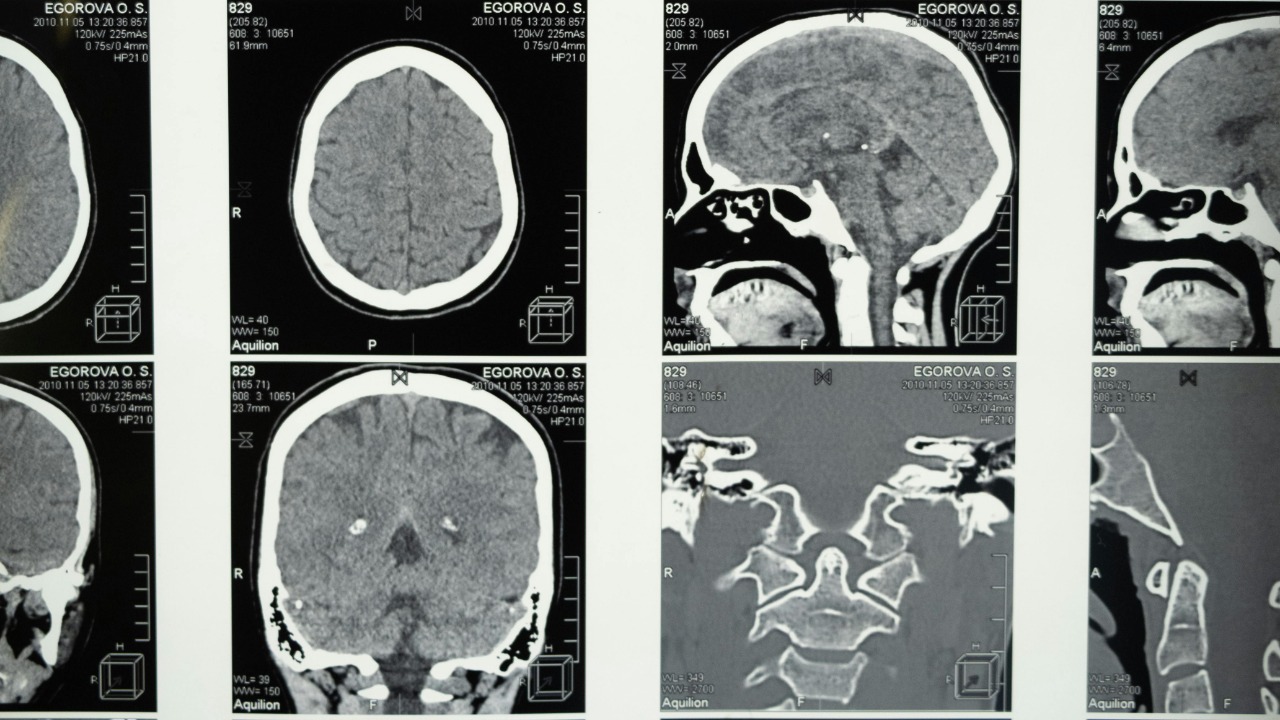

Glioblastoma is the kind of diagnosis that redraws a life in an instant, a brain cancer so aggressive that survival is usually measured in months and not years. For decades, surgery, radiation and chemotherapy have barely nudged the statistics, and there is still no approved cure. Now, a series of converging advances is giving researchers something they have rarely had in this field: a plausible kill switch that might shut down the disease at its molecular core.

Instead of relying on one magic bullet, scientists are zeroing in on the wiring that lets glioblastoma grow, spread and evade the immune system, then designing tools to cut those circuits. From a newly druggable gene that appears to drive the tumor, to cellular “motors” that can be jammed, to immune cells and gene therapies programmed to hunt cancer, the landscape is shifting from damage control to the possibility of durable control.

From “master switch” to AVIL: the gene that keeps glioblastoma alive

More than a decade ago, researchers studying glioblastoma and melanoma described a possible molecular “master switch” that seemed to sit high in the chain of command that controls how these cancers behave. That early work on a regulatory hub in Glioblastoma helped set the stage for a new wave of research that treats the disease less as a solid mass and more as a network of signals that can be interrupted. The idea was simple but radical at the time: if you can find the switch that cancer cells depend on, you might not need to hit every cell individually.

That logic is now crystallizing around a gene called AVIL. At UVA Health, Hui Li and colleagues have identified AVIL as a critical driver in the deadliest form of brain cancer, showing that it is consistently switched on in glioblastoma cells while being largely dispensable in normal brain tissue. In follow up work, the team has detailed how AVIL normally helps cells maintain their size and shape, but when pushed into overdrive by cancer, it becomes a vulnerability that can be targeted. By designing a small molecule that interferes with this gene’s activity, they have opened a path to a therapy that aims not just to slow tumors, but to switch off a function they cannot live without.

A new pathway and a potential kill switch

The AVIL work is more than a single-gene story, it is a map of a previously untapped pathway that glioblastoma cells use to survive. In laboratory models, blocking this route with a tailored molecule has sharply curtailed tumor growth, suggesting that the cancer is unusually dependent on this line of signaling. According to a detailed report on the project, the researchers describe the AVIL axis as a pathway that, to their knowledge, had not been therapeutically exploited before, a point underscored in a release from the Comprehensive Cancer Center that supports the work. That kind of language is rare in a field where most targets have been tried and found wanting.

What makes this feel like a true kill switch is the combination of specificity and leverage. Glioblastomas are tumors that arise from glial cells and are usually highly malignant, with a tendency to infiltrate healthy brain and resist standard drugs, as summarized in an overview of Can this new molecule block a glioblastoma-driving gene. By homing in on AVIL, which appears to be essential for the cancer but far less so for normal cells, the UVA team is trying to thread a needle that has eluded previous drugs. Local coverage of the project has emphasized that Researchers see this as a stride toward treating what they call the most deadly brain tumor, even as they caution that clinical use is still years away.

Cellular motors and the physics of a lethal tumor

While gene-focused work tries to cut power to the tumor’s control room, another line of attack is going after the machinery that lets glioblastoma cells move and divide. At The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute, scientists have zeroed in on molecular “motors” that shuttle cargo inside cells and help them change shape, a process that is crucial for invasion into surrounding brain tissue. In a pair of studies, they showed that drugs aimed at these motors could wipe out aggressive brain cancer tumors in preclinical models, a striking result highlighted in a report from Wertheim UF Scripps. By disrupting the physical engines that glioblastoma cells rely on, the team is effectively trying to strand the cancer in place and starve it of the internal transport it needs.

The same group has described its approach as out of the box, arguing that targeting these motors opens a new route to attacking the hardest to treat glioblastoma. In a broader analysis of their work, they outline how Their strategy works in four distinct ways, including disrupting tumor cell movement and survival, while also flagging toxicity as a key concern that will have to be managed in any future trials. For patients, the appeal is obvious: if a drug can selectively jam the motors that cancer cells use, without stalling healthy neurons, it could complement genetic kill switches like AVIL and make it harder for the disease to adapt.

Reprogramming the immune system with CAR-T and switchable cells

Even the best targeted drug will struggle if glioblastoma can hide behind the brain’s defenses, which is why immunotherapy is becoming the third pillar of this emerging strategy. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, better known as CAR-T, has already transformed some blood cancers by genetically engineering a patient’s own immune cells to recognize and kill tumor cells. In glioblastoma, early studies indicate that Chimeric antigen receptor T cells can bypass some of the barriers imposed by the GBM microenvironment, although the solid tumor setting remains far more challenging than leukemia or lymphoma.

To overcome those hurdles, researchers are layering new control systems onto CAR-T cells. One group has developed a “synNotch” based design that uses a two step process to kill glioblastomas, first sensing one marker and then activating a CAR only when the right combination is present. The work, led by Wendell Lim, Ph. D., is described as a way to make engineered cells more precise and safer, with Wendell Lim describing how the team’s approach could be adapted for both adults and children. In parallel, scientists at another center have engineered what they call switchable CAR-T cells, or CAT T cells, that can be turned on or off with a separate molecule, a concept explained in a short video from CAT researchers at UCSF. Together, these designs hint at a future in which immune cells can be dialed up to attack glioblastoma and then dialed back to limit collateral damage.

Gene therapy and combination strategies edging toward patients

Beyond drugs and immune cells, gene therapy is starting to move from theory to planned trials in glioblastoma. At the University of Edinburgh, a new study is preparing to test a viral vector that delivers a therapeutic gene directly into brain tumors, with the goal of infecting the cancer cells and turning them into factories for their own destruction. The project is part of a broader push in which What is described as a new trial for brain tumour patients will use gene therapy to spread a toxic effect from an infected cell to its neighbours, potentially reaching infiltrating cancer that surgeons cannot see. Advocates are careful to explain what gene therapy involves, stressing that it is about delivering genetic instructions rather than editing a patient’s DNA in place.