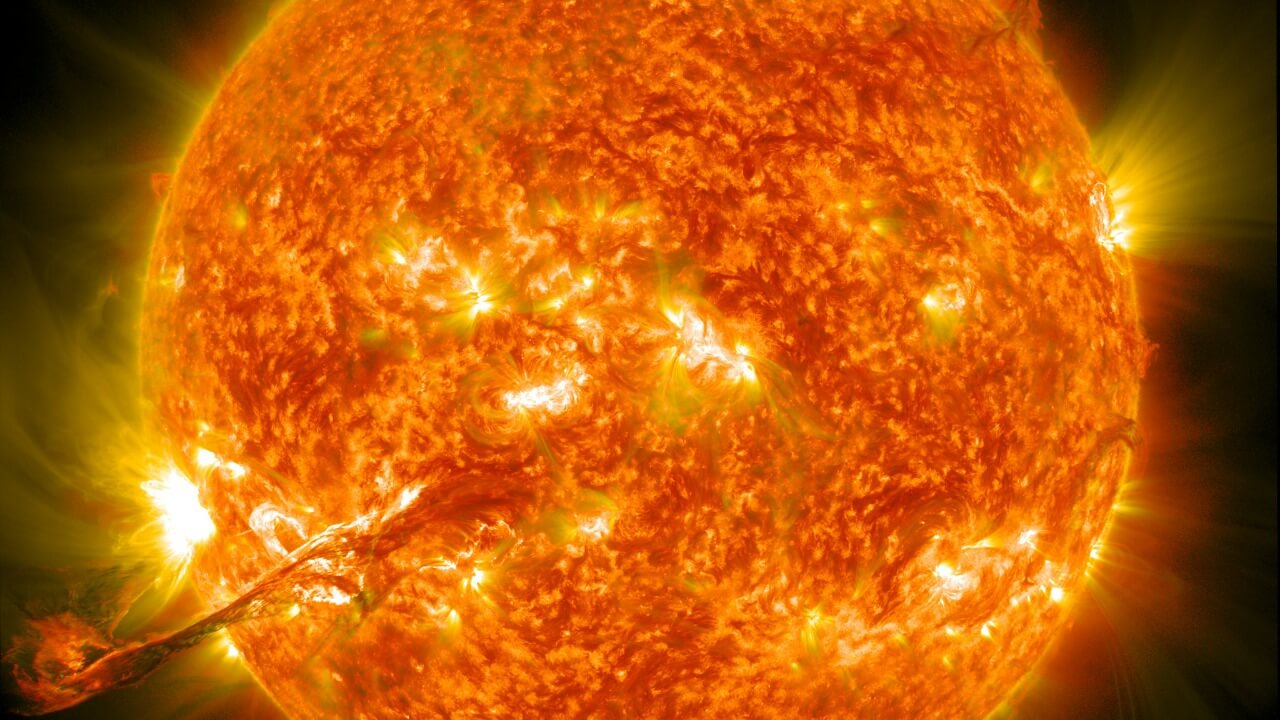

For a few days in early 2023, it looked as if the Sun itself had come apart. Images from solar observatories showed a bright filament near the star’s north pole snapping free and swirling into a tight loop, a sight that left even veteran researchers describing the scene as baffling and “very curious.” The spectacle fed a wave of viral claims that a piece of our star had broken off, raising fresh questions about what is really happening on the surface of the Sun.

I see that moment less as a cosmic disaster than as a reminder of how dynamic, and how misunderstood, our nearest star still is. The apparent “break” was real enough in the images, but the physics behind it turns out to be stranger, subtler and far more routine than the headlines suggested.

What actually “broke off” the Sun

The drama began when a towering solar prominence near the Sun’s north pole suddenly detached and appeared to shear away from the surface. According to reporting from Feb 10, 2023, scientists watching live data saw a huge filament of solar plasma lift off and then wrap itself into a tight polar vortex, a configuration that even seasoned Scientists described as baffling and exciting. In the raw imagery, it looked like a clean fracture, as if a chunk of the solar rim had snapped off and started to spin on its own.

What actually moved was not solid material but a looping river of charged gas guided by magnetic fields. Earlier coverage on Feb 10, 2023, noted that, According to NASA, the prominence was a large bright feature extending outward from the Sun’s surface, part of the same restless atmosphere that regularly throws off flares and coronal mass ejections. There have been many such prominences before, but this one’s position near the pole and its tight, hurricane like swirl made it look, in the words of one account, like a piece of the solar edge had simply broken free.

Why scientists were stunned but not scared

From my vantage point, the most revealing part of the story is how quickly solar physicists moved from shock to explanation. In coverage dated Feb 9, 2023, experts pointed out that Unusual activity typically occurs at the Sun’s 55-degree latitudes once every 11-year solar cycle, a belt that plays a key role in how the star’s magnetic field flips and reorganizes. The detached filament appeared to form right in this region, suggesting that the same deep magnetic processes that drive the cycle were also shaping this strange vortex.

By Feb 15, 2023, the tone among researchers had shifted from alarm to curiosity. A detailed radio segment explained that a part of the Sun had broken off and was swept up in a polar vortex, but Scientists stressed that the event was not as dangerous as it sounded. The swirling plasma stayed close to the solar surface, far inside the region that contains the orbit of Earth, and there was no sign of an unusually strong blast heading our way. In other words, the spectacle was a puzzle for theorists, not a threat to satellites or power grids.

The truth behind the viral “broken Sun” headlines

Once the images hit social media, the narrative quickly outran the science. I watched as posts claimed that a “chunk” of the Sun had snapped off, language that suggests a solid object cracking like ice. That framing was always misleading. A detailed explainer from Feb 11, 2023, noted that the last few days had seen a flood of such claims, and then walked through what really happened: a filament of plasma, shaped by magnetism, detached and circulated around the pole, a rare geometry but still part of normal solar behavior, as one Feb analysis made clear.

Fact checkers soon weighed in as well. A review published on Feb 13, 2023, put it bluntly in its Conclusion: no part of the Sun has broken off, and the recent phenomenon was a rare but periodic solar activity, according to scientists. That assessment fits with decades of observations showing that prominences, filaments and polar structures come and go as the magnetic cycle evolves. The Sun looked “broken” only if you froze a single frame and ignored the restless, fluid nature of the star itself.

For me, the episode is a case study in how modern space weather coverage works. High resolution imagery and real time feeds let the public see the Sun with the same immediacy as the experts, but they also invite snap interpretations that can turn a routine, if spectacular, solar event into an imagined catastrophe. The reality, grounded in the work of Feb, Sun watchers and patient modelers, is stranger and more beautiful than the viral shorthand: a star whose surface never stops boiling, twisting and, occasionally, spinning its own storms into shapes we have never quite seen before.