For decades, Europa has been the optimistic counterpoint to a lonely universe, its buried ocean held up as one of the most promising habitats for alien microbes. A new wave of research now argues that the story under that ice may be far more austere, with a quiet seafloor that struggles to deliver the energy life would need. Instead of a hidden analogue to Earth’s deep oceans, Europa may be closer to a frozen archive, chemically interesting but biologically still.

The latest study reframes the question from “Is there water?” to “Is there power?” and finds that Europa’s interior may simply not be active enough. That shift in focus, from liquid oceans to the engines that stir and heat them, is what now casts doubt on the prospects for life beneath the ice.

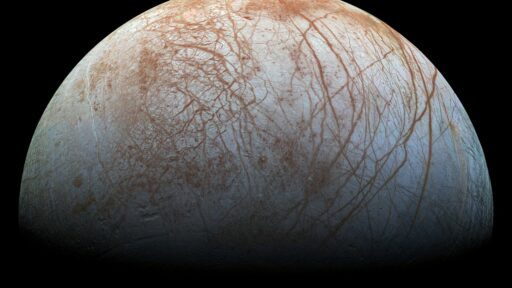

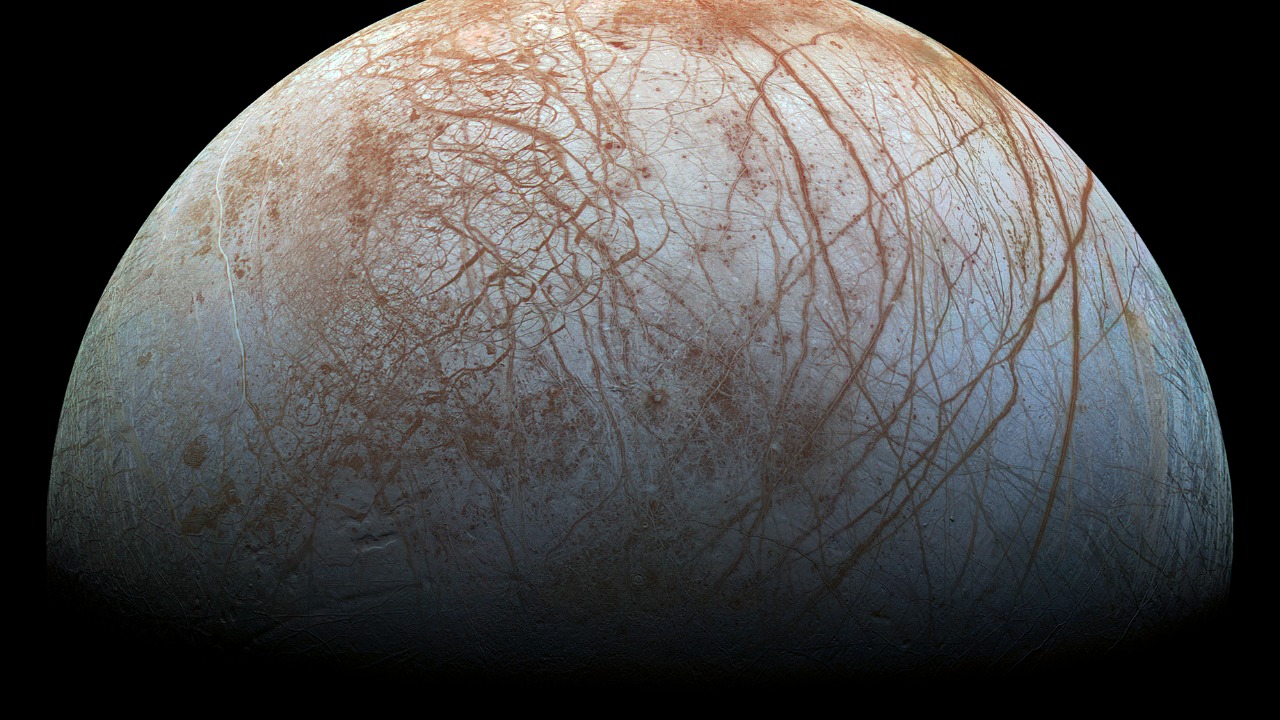

Europa’s deep ocean, thick ice, and a surprisingly quiet seafloor

Early enthusiasm for Europa rested on a simple recipe: a global ocean, a rocky seafloor, and tidal flexing from Jupiter that could fuel hydrothermal vents. Scientists now argue that the details of that recipe look less favorable. New modeling of Ice Shell Thickness suggests Europa’s frozen lid is between 15 and 25 km thick, with a very deep ocean beneath it, which makes any exchange of chemicals between the surface and the interior more difficult. That depth also means less tidal stress reaches the rocky core, weakening the forces that might otherwise drive volcanism on the seafloor.

The same work points to a relatively cool and rigid interior that does not deform as vigorously as some earlier models assumed. The researchers considered Europa’s size, the composition of its rocky core, and the gravitational forcing from Jupiter and neighboring moons, and concluded that the stresses are probably too weak to sustain widespread magmatic activity. If the rock at the bottom of the ocean is largely cold and immobile, then the seafloor becomes more like a passive boundary than a dynamic engine, with limited fresh rock, heat, or nutrients being delivered into the water column.

Hydrothermal energy shortfall and the “dead zone” concern

On Earth, deep-sea ecosystems cluster around hydrothermal vents, where hot, mineral-rich fluids gush from the crust and power chemosynthetic life. The new Europa study finds that such vents may be rare or absent. One analysis concludes that There would likely or seamounts, and that hydrothermal activity such as black smokers would be extremely limited. Without those hot spots, the ocean may lack the chemical gradients that microbes exploit, leaving a vast volume of water with very little usable energy.

That picture is echoed in detailed geophysical modeling of the moon’s interior. In one set of calculations, researchers describe how don’t see any shooting out of the ice today like those on Io, and the predicted tidal heating in Europa’s rock is too weak to generate similar eruptions at the seafloor. The result is a world where the ocean satisfies the requirement for liquid water but may fall short on sustained energy sources, a combination that leaves habitability in serious doubt.

From “best bet” to cautious optimism as missions close in

Even as the new work tightens the energy budget, planetary scientists are not ready to write Europa off. One of the study’s authors, Christian Klimczak, stresses that, Given what we know about Europa, it is still the best place to look for extraterrestrial life in the outer solar system. The key shift is that the search may need to focus on more marginal niches, such as isolated warm spots or regions where oxidants from the surface trickle down into the ocean, rather than a globally teeming biosphere.

Other researchers frame the new results as a refinement rather than a reversal. In one summary, scientists note that Scientists Say Europa has an Ocean May Be Too Quiet for Life, and that New Research Challenges the Idea of a Living Seafloor, but they also emphasize how little direct data exist. The upcoming Europa Clipper mission will not orbit the moon. Instead it will perform a series of high speed dives that bring it to within 25 km of the surface, a strategy that, as one analysis notes, means the spacecraft Instead it’ll perform repeated flybys to sample the environment without being destroyed by Jupiter’s radiation.

A “quiet and lifeless” seafloor, but still a crucial test case

The most sobering language comes from geologist Paul Byrne, who describes Europa’s quiet seafloor geology as offering little support for any contemporary life beneath the ice. In his view, Everything Would Be Quiet, with a crust that behaves more like Earth’s present-day Moon than a restless mid-ocean ridge. That image of stillness has led some commentators to describe Europa as a potential Dead Zone in the Search for Alien Life, a place where water exists but biology never gains a foothold.

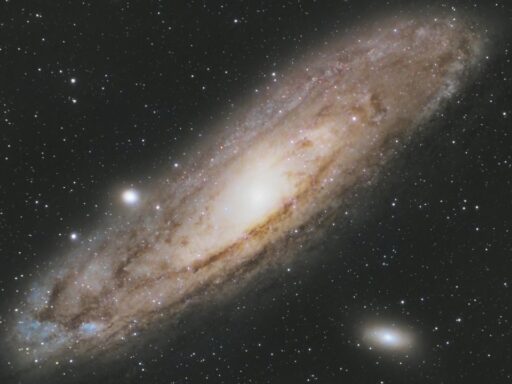

Yet even a negative result would reshape how I think about habitable worlds. Jupiter is surrounded by nearly 100 known moons, and one report notes that the giant planet Jupiter has nearly 100 k objects in its broader system when smaller bodies are counted, yet only a handful, including Europa, have ever looked remotely promising for life. If Europa’s ocean turns out to be sterile, that will sharpen the criteria for habitability around other stars, pushing astronomers to look not just for water but for signs of internal heat and active geology. As one synthesis of the new work puts it, Jupiter’s Moon Europa may have a seafloor that is quiet and lifeless, but that still makes it one of the most important laboratories for understanding where life can, and cannot, take hold.