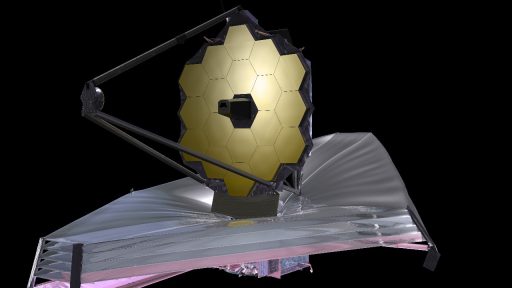

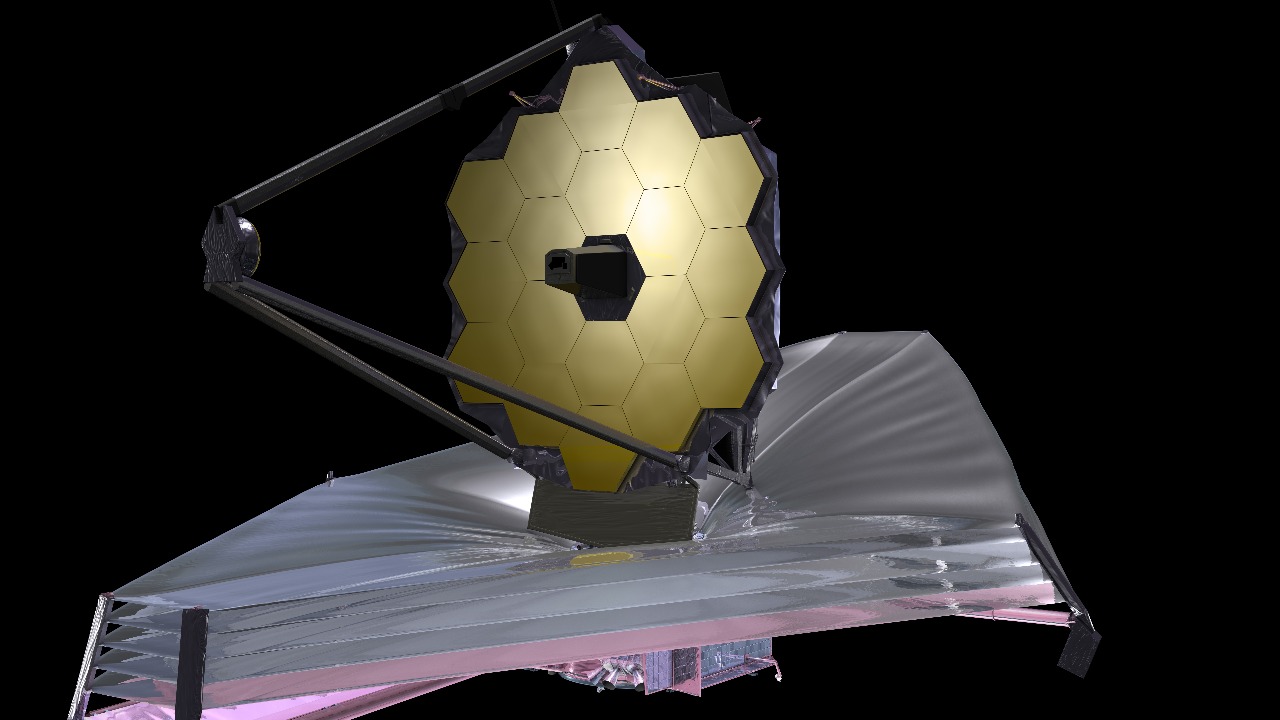

The James Webb Space Telescope is not circling our planet the way most people picture a satellite. Instead, NASA parked it in a delicately balanced orbit around a gravitational sweet spot, a place in deep space where the pull of the Sun and Earth line up just right. That choice of orbit is as radical as the telescope’s technology, and it is the quiet reason Webb can peer back toward the first structures that formed after the Big Bang.

To understand why this orbit is so unusual, it helps to remember how far from home Webb really is. While Hubble loops just 560 kilometers above the Earth, Webb travels around the Sun roughly 1.5 Million kilometers away from our planet, a distance that turns routine servicing into an impossibility but unlocks a new kind of observatory.

Why Webb lives at the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange point

Engineers did not send Webb into a conventional Earth orbit because the telescope’s infrared eyes need a stable, cold, and dark environment that low orbit simply cannot provide. Instead, the mission team targeted the second Sun–Earth Lagrange point, or L2, a location where the gravity of the Sun and Earth, combined with the spacecraft’s motion, allow it to keep pace with our planet as both circle the Sun. In practical terms, Webb orbits the Sun near this Sun–Earth Lagrange point at about 1.5 M kilometers from Earth, a configuration that keeps the spacecraft in a constant geometric relationship with our planet and star while still counting as a Solar Orbit rather than an Earth orbit, as detailed in mission descriptions of Webb’s overall Key Facts.

At L2, Webb does not sit motionless at a single point, it traces what physicists call a halo orbit around that gravitational balance. Technical summaries describe how Webb operates in a halo orbit circling the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange point, roughly 1.5 m kilometers (about 1,000,000 miles) from Earth, a placement that keeps the Sun, Earth, and Moon all on the same side of the spacecraft so its sunshield can block their combined glare and heat. That halo path is crucial, because it prevents the telescope from falling directly into the unstable Lagrange point itself while preserving the line-of-sight geometry that makes communications and thermal control manageable, a structure laid out in detail in discussions of Webb’s Location and orbit.

How this “mind-blowing” orbit actually works

From a distance, it is tempting to imagine Webb simply hanging behind Earth like a car drafting in another vehicle’s slipstream, but the dynamics are more subtle. Educational explainers emphasize that The James Webb Space Telescope is not in orbit around the Earth at all, it is in a Solar Orbit, looping around the Sun while staying roughly a million miles from Earth at the second Lagrange point. In that configuration, the spacecraft constantly falls around the Sun in step with our planet, using small thruster burns to maintain its halo path around L2, a behavior that is very different from the tight, fast circles flown by satellites in low Earth orbit and is captured clearly in visualizations of Webb’s Orbit.

For non-specialists, the counterintuitive part is that an object farther from the Sun normally orbits more slowly, yet Webb keeps pace with Earth. As one plain-language explanation notes, this is exactly what makes L2 special: Normally, things that are farther from the Sun orbit more slowly than things that are nearer, but at L2 the combined gravity of the Sun and Earth effectively speeds up the spacecraft just enough to match Earth’s orbital period. That balance lets Webb share Earth’s year while sitting well beyond the Moon, a point that has been broken down for general audiences in discussions of how Lagrange points tweak the usual orbital rules around the Sun.

Why this orbit is perfect for seeing the early Universe

The choice of L2 was not just a clever orbital trick, it was a scientific necessity. Webb studies every phase in the history of our Universe, from the first luminous glows after the Big Bang to the formation of galaxies, stars, and planetary systems, and that mission demands extreme sensitivity to faint infrared light. To reach that sensitivity, the telescope must stay cold and shielded from stray heat, which is why engineers designed the observatory so that its sunshield always faces the Sun and Earth while the mirror and instruments stare into deep space, a requirement that shaped the decision to place Webb at L2.

From this vantage point, Webb can maintain a nearly constant thermal environment, with its hot side always turned toward the Sun and its cold side permanently shaded. Training materials describe how JWST sits about a million miles from Earth at the second Lagrange point in a Solar Orbit, with its multilayer sunshield keeping the telescope’s cold side chilled so that its detectors can pick up faint heat signals from distant galaxies rather than warmth from the spacecraft itself. That stable, cold backdrop is what allows The James Webb Space Telescope to push far beyond Hubble’s capabilities and capture the kind of ultra-deep infrared views of the early Universe that motivated the mission in the first place, a design logic laid out in educational modules on JWST.