NASA is about to test whether a return to the Moon can still galvanize the country in an era when Mars has become the ultimate prize. Artemis 2, the first crewed flight of the new lunar program, is being treated inside the agency as a make-or-break step, even as concrete plans for human missions to the Red Planet recede into the distance. The bet is simple: prove that a sustainable presence around the Moon is possible, and only then argue for the far more expensive leap to Mars.

The high-stakes shakedown cruise around the Moon

Artemis 2 is designed as a stress test of the entire deep space stack, from the Space Launch System rocket to The Orion capsule and the European Service Module for the Artemis II, before anyone attempts a landing. Official planning now pegs the earliest launch window to no earlier than February 6, 2026, with the mission framed as a roughly ten day loop around the Moon that will push human spaceflight farther from Earth than at any time since Apollo. That schedule, and the hardware configuration behind it, is laid out in detail in the program’s technical overview of Artemis II.

Inside NASA, Artemis 2 is explicitly billed as the first crewed mission on the agency’s path to establishing a long term presence on and around the Moon, a role that makes it far more than a symbolic reprise of Apollo. Agency materials describe how Four astronauts will venture around the Moon to validate life support, navigation and reentry systems that will be reused on later flights. The mission profile, which keeps the crew in lunar orbit rather than attempting a landing, is meant to wring out risk while still delivering the first human voyage to the Moon’s vicinity in more than fifty years.

From rollout to crew, Artemis 2 is the Moon-first pivot in action

The political and operational machinery behind Artemis 2 is now moving at full speed, underscoring how central this flight has become to NASA’s near term agenda. Agency officials say they are working toward a February launch of Artemis 2, with internal planning assuming that the massive Space Launch System will have only a handful of viable launch days each month because of orbital mechanics and range constraints, a cadence described in detail in the update that NASA continues to work toward. On the ground in Florida, NASA Comms Bethany Stevens has already told followers that rollout of the Artemis II SLS to the pad is expected in the coming weeks, a milestone echoed in coverage of the Artemis II SLS preparations.

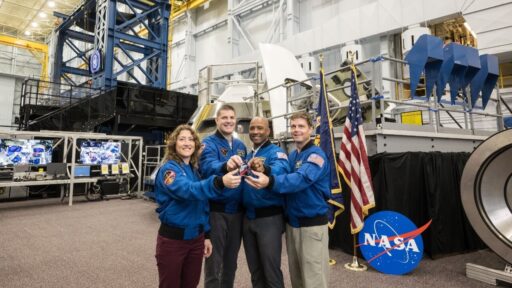

The rocket itself has become a kind of rolling billboard for the Moon-first strategy. Reporting on the vehicle’s final assembly notes that NASA’s Artemis 2 rocket will carry special decals to mark America’s 250th anniversary, a detail highlighted in a preview that quotes Featured writer Seth Kurkowski Jan describing how the rollout is expected in less than two weeks. The crew has been equally prominent: Artemis II will send a group of four astronauts, including NASA’s Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch as well as a Canadian Space Agency representative, on a trip around the Moon, a lineup spelled out in a mission overview that profiles Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch. For NASA, putting such recognizable faces on a lunar flyby is a way to signal that the Moon, not Mars, is where the agency’s human spaceflight energy is concentrated for the rest of this decade.

Moon to Mars on paper, Mars on pause in practice

Officially, Artemis is still marketed as part of a broader “Moon to Mars” architecture, a phrase that appears prominently in technical planning documents. Those guidelines, described as “On the more technical side” of NASA’s exploration strategy, lay out how the Moon and Mars are supposed to be linked in a single roadmap, with the Moon serving as a proving ground for technologies and operations that will eventually support Mars expeditions, a relationship detailed in the analysis of On the Moon to Mars framework. Program documentation for the broader Artemis effort reinforces that sequence, noting that Artemis II (2026) is planned as a key step in a campaign that aims to build a sustainable presence in lunar orbit and on the surface no later than April 2026, a target embedded in the description of the overall Artemis program.

Yet when it comes to Mars itself, the gap between rhetoric and reality is stark. During the confirmation process for the current NASA administrator, Jared Isaacman, senators were told that Currently, NASA does not have any concrete plans to send humans to the red planet, even though the agency has routinely talked about eventual Mars (the red planet) missions, a disconnect spelled out in testimony summarized under the phrase Currently, NASA. The Trump administration’s budget priorities have sharpened that focus: proposed cuts explicitly prioritize human spaceflight, specifically returning to the Moon and sending humans to Mars (the Red Planet) at the expense of broader scientific discovery and international collaboration, a tradeoff described in detail in the analysis of how the Mars, Red Planet push is reshaping NASA’s portfolio. In practice, that has left Artemis 2 as the flagship of a Moon-first era, while Mars remains a destination that exists mostly in PowerPoint.

Within that context, Artemis 2 is being framed as both a capstone to the Apollo legacy and a bridge to whatever comes next. Analysts point out that Artemis 2 will be the first mission to carry humans toward the Moon since NASA’s Apollo program ended in 1972, a milestone highlighted in a mission explainer that notes how Artemis 2 must clear a series of final testing and integration milestones before flight. Policy analysts have also emphasized that NASA’s Artemis II mission, currently planned for no later than April 2026, is intended to demonstrate capabilities that will be essential for future crewed missions to Mars, a linkage spelled out in a briefing on how NASA sees the mission. Public outreach has leaned into that narrative as well, with coverage noting that Koch and the other members of the crew will rehearse the kinds of conditions they might encounter around the Moon that are relevant to later Mars expeditions, a point underscored in a feature on why Koch and the other members of the crew are being trained for contingencies that look beyond a single flight. For now, though, the only concrete ticket off Earth that NASA can sell to its astronauts is a loop around the Moon.