The first soft landing on Mars lasted barely longer than a deep breath. The Soviet Mars 3 spacecraft reached the surface, began transmitting, produced a single murky frame, and then fell silent after roughly 14 seconds, leaving engineers with more questions than data. Half a century later, that brief whisper from another world still shapes how I think about risk, failure, and ambition in planetary exploration.

Today, when China and the United States operate sophisticated rovers and the UAE studies the planet from orbit, it is easy to forget how audacious that first touchdown was. Mars 3 arrived at a world wrapped in dust, carrying technology that had never faced such conditions, and its disappearance turned into one of spaceflight’s most haunting near-misses.

The first landing that almost no one saw

By the early 1970s, the Soviet program had already endured hard lessons at Mars, including the crash of its sister probe Mars 2, yet it still pushed ahead with a lander designed to survive Entry, descent, and touchdown on a planet no one had ever visited in person. The combined Mars 2 and Mars 3 campaign, sometimes labeled Mars M71, sent orbiters and landers toward a world that, at the time, was still largely a blur in telescopes and grainy flyby images. According to mission records, Mars 3 was successfully sent toward Mars in late May 1971, part of a broader push to secure a first in the race to the Red Planet.

When the lander separated and plunged into the atmosphere, it was heading for a site near 45 degrees south and 202 degrees east, coordinates later cited as 45 and 202 in technical descriptions of the touchdown point. After Entry and descent, the craft reached the surface and began sending a television signal that should have built up a panoramic view line by line. Instead, the transmission broke off almost immediately, leaving only a fragmentary image that shows a mottled pattern many analysts interpret as a dust-shrouded landscape. The official account notes that the lander began transmitting but failed within seconds, with the harsh lighting and storm conditions likely contributing to the poor quality of the lone frame.

A dust-choked world and a 14‑second mystery

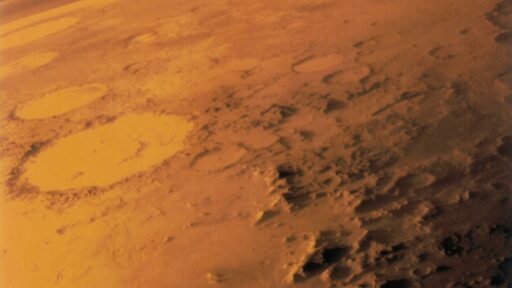

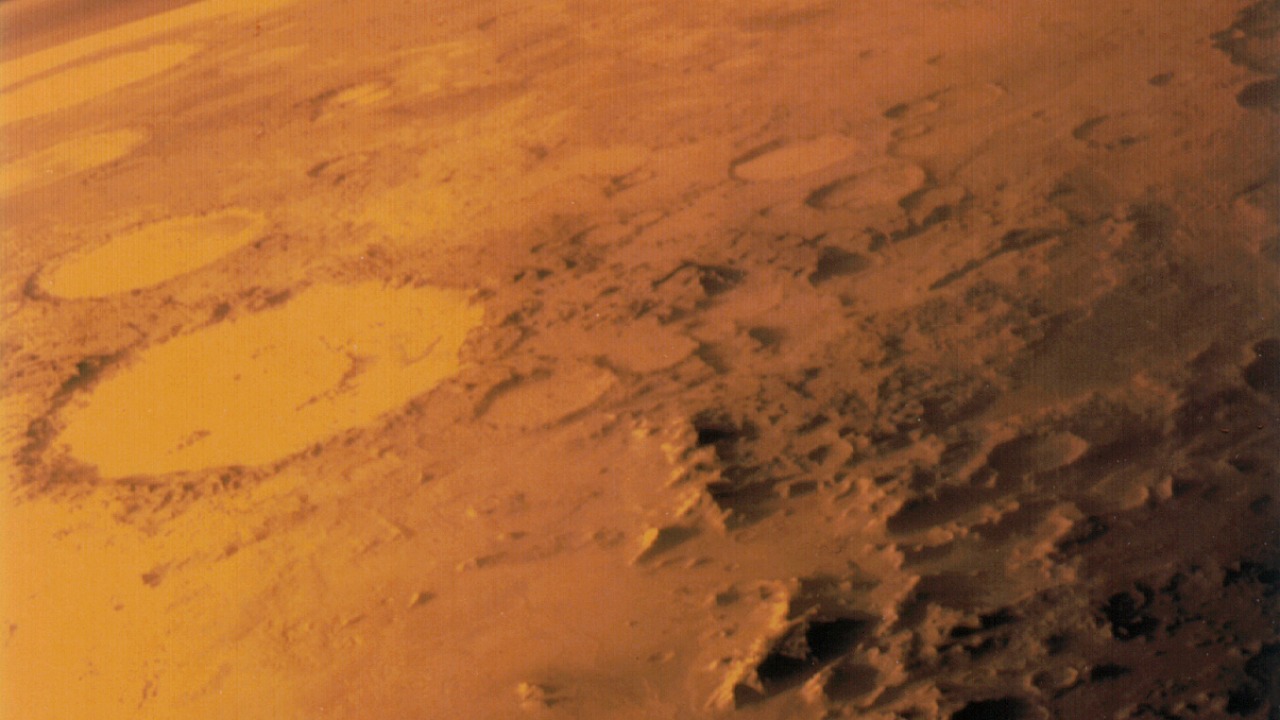

The timing of Mars 3’s arrival could hardly have been worse. When the Russian orbiter component reached Mars late in 1971, it found the planet wrapped in a global dust storm that obscured surface features and turned the atmosphere into a churning haze. Images from that period show Mars 3 arrives to a dust-shrouded planet, with the storm so intense that it likely battered the descending capsule and may have interfered with its radio link. Engineers later suggested that electrical discharges in the dusty atmosphere or mechanical damage on impact could have cut the transmission after those fateful 14 seconds.

Even with the truncated signal, Mars 3 secured a place in the official catalog of Missions to Mars as the first craft to achieve a soft landing on the surface. In that list, the entry for Mars 3 notes that On December 2 it became the first successful lander, even though its surface operations ended almost as soon as they began. Decades later, the story resurfaced when enthusiasts poring over high resolution images from Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spotted a cluster of unusual shapes near the expected landing site. Their sleuthing prompted a closer look at the data, and a subsequent analysis suggested that Mars orbiter images may show the discarded parachute, heat shield, and even the lander itself, scattered across the dusty plain.

From forgotten failure to quiet foundation

For years, Mars 3 was treated as a historical footnote, overshadowed by later triumphs on Mars and by the Soviet program’s own frustrations. One retrospective described it as part of a Soviet Mars shot that almost everyone forgot, a mission remembered mainly by specialists and space historians. Yet the attempt marked a turning point. It showed that a controlled descent to the Martian surface was possible, even under extreme conditions, and it forced designers to confront how dust, thin air, and communication delays could conspire to erase a billion-ruble spacecraft in seconds.

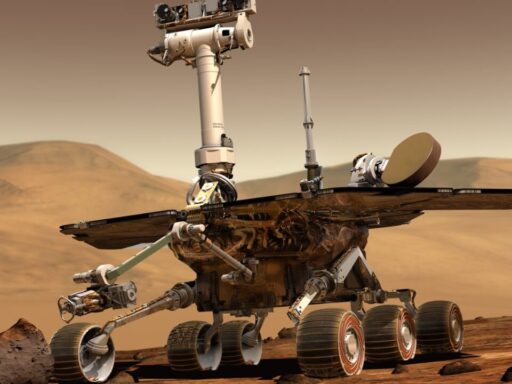

The broader context makes that achievement even starker. Half a century later, Mars has become a crowded destination, with China and the United States operating rovers and the UAE flying an orbiter that studies the atmosphere and weather patterns. One detailed look back noted that Mars has become quite the hot spot, yet the early Soviet landers still carry their own mix of glories and disappointments. In that same reflection, Mars 3 is described as a mission that was meant to deploy a small rover but lost contact after just 110 seconds, with only one grainy image to show for the effort, a reminder that even ambitious plans can be cut short. The figure 110 appears in that account as the expected surface operations window, a contrast to the roughly 14 seconds of usable data that actually reached Earth.

The afterlife of a 14‑second signal

What keeps Mars 3 from fading entirely into obscurity is the way its story has been reclaimed by a new generation of enthusiasts and archivists. On social media, space heritage projects mark the date as a milestone, noting that On December 2, 1971, a Soviet spacecraft became the first to land on Mars for the record, an event now framed as happening 54 years ago. That kind of commemoration turns a failed surface mission into a cultural touchstone, a way to connect current exploration to the analog electronics and hand-drawn schematics of an earlier era.

There is also a technical afterlife. The same retrospective that called Mars 3 forgotten points out that it was supposed to release a tiny rover, a concept that foreshadowed the mobile laboratories now roaming Jezero and Utopia Planitia. In that account, Mars 3 was meant to deploy a small vehicle, but the loss of contact made that impossible. Years later, Russian citizen scientists, inspired by news about Mars and NASA’s Curiosity rover, combed through orbital images and identified four suspicious features in a single frame, prompting a closer review of how While following news about Mars and NASA can lead to fresh discoveries about older missions. In that sense, the 14 second transmission has never fully ended. It continues to echo in the data, the archives, and the ambitions of every team that tries to do better on the next descent.