Most of the universe is missing from our telescopes. The stars and galaxies we see are threaded through a far larger web of dark matter and dark energy that does not shine, yet dictates how everything moves. By tracking subtle warps in distant galaxies, astrophysicists are now turning this invisible scaffolding into detailed maps that test our best theories of cosmic evolution.

Those distortions, tiny stretches and smears in galaxy shapes, are not camera glitches. They are the imprint of gravity itself, bending light as it travels across billions of light years. I see this technique rapidly shifting from a clever trick of general relativity into a precision tool, one that lets researchers weigh the cosmos, chart hidden structures and probe why the expansion of space is speeding up.

How warped galaxies expose the dark universe

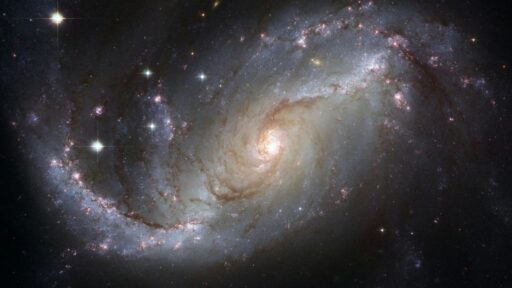

The basic idea is disarmingly simple: mass curves spacetime, and curved spacetime bends light. When a massive structure sits between us and a distant galaxy, its gravity acts like a lens, slightly distorting the galaxy’s apparent shape. This effect, known as Gravitational lensing, lets scientists infer how much mass lies along the line of sight, even when that mass is dark. By stacking measurements from millions of galaxies, researchers can reconstruct sprawling maps of dark matter and track how it clumps over time.

According to Einstein’s theory, light follows the curvature of spacetime, so any deviation from a galaxy’s expected shape can be translated into a map of the intervening mass. As one researcher put it, traditional optics are useless for something that does not emit or absorb light, but gravity itself becomes the instrument. That logic underpins projects where students and scientists alike use lensing to study regions that are “packed with dark matter,” as described in work on mapping the invisible. The result is a new kind of cartography, one that charts the unseen mass shaping the visible universe around us.

From early dark maps to today’s precision surveys

The first large-scale dark matter maps already hinted at the power of this approach. More than a decade ago, astronomers measured warped light from about 10 million distant galaxies across several sky patches to build what was then the biggest map of the invisible cosmos. By tracking how that warped light traced filaments and voids, they confirmed that dark matter forms a vast cosmic web, with galaxy clusters sitting at its densest knots. Those early efforts were noisy and relatively low resolution, but they proved that weak lensing could weigh structures on scales far beyond any single cluster.

Since then, the technique has sharpened dramatically. Surveys using instruments like the 570‑megapixel camera of the Dark Energy Survey have pushed lensing measurements to fainter galaxies and wider areas, tightening constraints on how dark matter clumps and how dark energy drives cosmic expansion. Earlier work showed that “Visible galaxies form in the densest regions of dark matter,” as Professor Ofer Lahav of UCL Physics and As emphasized, and modern maps now resolve those dense regions in unprecedented detail. The picture that emerges is of a universe where the luminous structures we catalog are merely tracers of a much larger, darker skeleton.

New telescopes, new maps, and what they reveal

Recent results show just how far this method has come. By studying tiny distortions in the shapes of distant galaxies, teams have produced wide-field reconstructions of dark matter and dark energy that align closely with the standard cosmological model. One analysis reported that by studying tiny distortions in galaxy images, scientists could trace how invisible structures affect the visible universe, while another highlighted how Galaxy warps help map dark matter and energy and reveal hidden features in the universe’s structure and evolution. Together, these studies strengthen the case that the prevailing “Lambda‑CDM” framework still matches reality, even as they expose small tensions that could hint at new physics.

Space missions are now scaling this effort to a new level. Using an initial sweep that covers just 0.4 percent of the sky, the Euclid spacecraft has already mapped 26 million galaxies, turning their distorted shapes into a first draft of the dark cosmos. Its early data show how Revealing the Hidden Universe Through Lensing can uncover arcs and multiple images that trace massive halos, potentially increasing the known population of strong lenses by up to 20 times. Ground-based facilities are keeping pace: the Rubin Observatory is expected to deliver the most precise map of the Universe ever, using repeated imaging to track weak lensing signals over half the sky.

All of this effort is driven by the realization that dark matter and dark energy dominate the cosmic budget. One explainer notes that Dark Matter makes up about 85% of the total mass in the Universe Dark, meaning the ordinary atoms in planets, people and stars are a rounding error. As another team put it, without this unseen component, our universe would look nothing like it does, because dark matter forms the “invisible skeleton” that shapes the visible universe around us. When I look at the latest lensing maps, I see not just technical triumphs but a profound shift in perspective: by reading the warps in faraway galaxies, we are finally sketching the true outline of the cosmos we inhabit.