Germany’s industrial revolution is still paying dividends, but only for some parts of the country. A new historical study finds that regions that embraced steam power in the late nineteenth century now enjoy higher wages, stronger innovation and deeper technical skills, even though the original engines are long gone. The findings suggest that the geography of today’s knowledge economy was etched into the map more than 150 years ago.

Instead of fading with time, the legacy of those early machines appears to have compounded, shaping where skilled workers live, where patents are filed and where companies pay more. The result is a persistent divide that complicates efforts to level up lagging regions and offers a stark warning as governments confront the next wave of general purpose technologies, from artificial intelligence to green industry.

Steam’s long shadow over German pay packets

The core claim of the new research is deceptively simple: the places that were early adopters of steam technology still pay better today. Regions where steam engines were particularly widespread at the end of the nineteenth century now have average wages that are 4.3% higher than comparable areas that industrialised more slowly, according to the study’s analysis of German labour market data. That premium may sound modest, but compounded across millions of workers and multiple decades it represents a substantial structural advantage for those historic industrial heartlands, and it persists even after controlling for modern economic differences.

The authors argue that this is not just a story about rich cities staying rich. They trace the pattern back to the diffusion of early industrial machinery, showing that the density of steam engines in specific Regions more than a century ago is still visible in today’s pay packets. The wage gap lines up with other indicators of economic dynamism, such as higher productivity and a greater concentration of firms in technology-intensive sectors, suggesting that the initial boost from mechanisation set off a chain reaction of investment, skills and innovation that has yet to run its course.

From factory boilers to modern innovation hubs

What makes the study striking is not only the wage effect but the way it connects nineteenth century machinery to twenty-first century knowledge work. Around 150 years on, those areas that first filled their factories with steam engines now have a larger share of workers with technical training and university degrees, as well as more patents and research activity. The researchers find that the early industrial base helped create local ecosystems of engineers, mechanics and entrepreneurs, which in turn made these places more attractive for later waves of technology and higher education.

This path dependence shows up clearly in the composition of the workforce. The share of employees with vocational qualifications in engineering and other technical fields is significantly higher in the historic steam belt, and universities and applied science institutes are more densely clustered there. According to the study, Around these former industrial hubs, the density of technically trained workers and university graduates is now markedly higher than in regions that missed the first steam wave, reinforcing the idea that early adoption of a general purpose technology can lock in a long term innovation advantage.

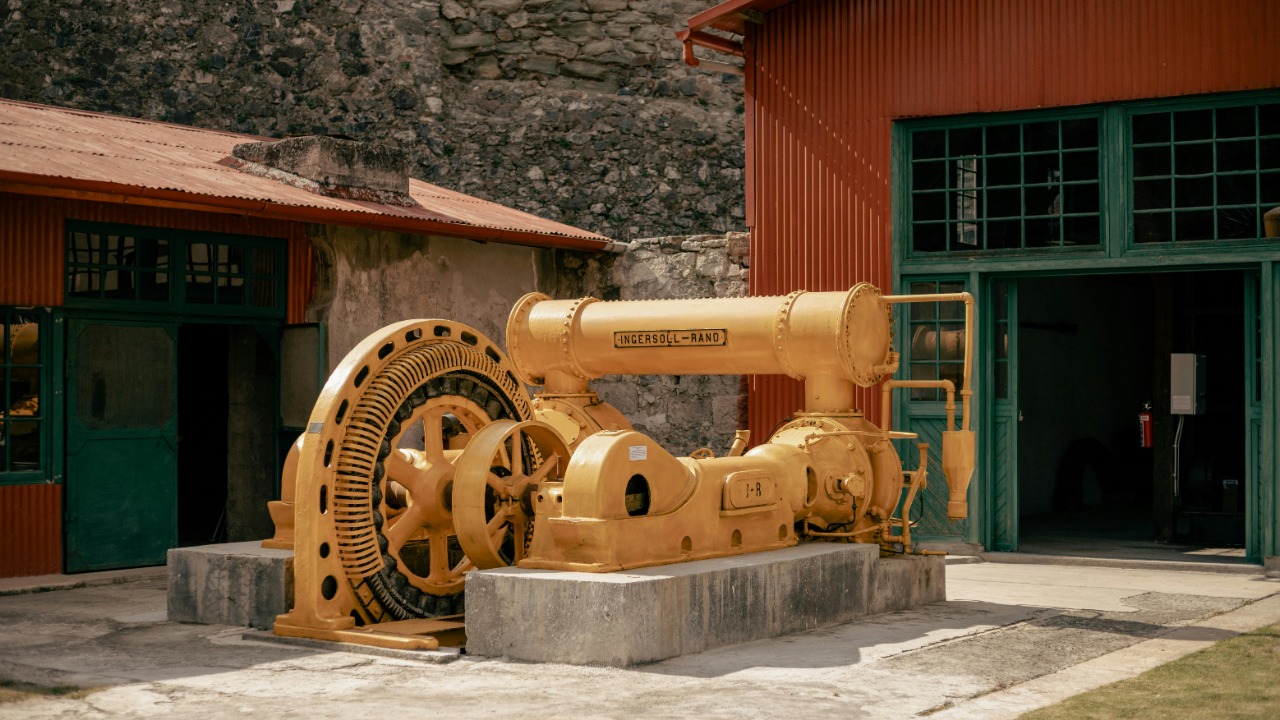

Steam engines as a textbook “general purpose” technology

Economists classify steam power as a classic general purpose technology, one that can be applied across many sectors and triggers broad organisational change. Historical evidence supports that view. At the time of industrialisation, steam operating industries did not just replace water wheels or animal power, they reorganised production, expanded factory size and altered the balance between labour and capital. One detailed historical analysis notes that, At the same time, though, since steam operating industries employed considerably more workers in total, they ended up using also more labour overall, even as the new machines concentrated control of production in the hands of capitalist owners.

This dual effect, higher productivity alongside a reshaped labour market, helps explain why the technology’s impact has been so persistent. The early steam adopters built up dense networks of suppliers, skilled workers and financiers that were hard for latecomers to replicate. As the study on German regions shows, those initial advantages translated into enduring gaps in wages and innovation, consistent with broader research on the labour market consequences of general purpose technologies. The lesson is that once such a technology takes root in particular places, it can shape economic geography for generations.

Self reinforcing cycles and the role of policy

The German evidence also highlights how technology can set off self reinforcing regional cycles. Once steam power made certain districts more productive and profitable, firms there could pay slightly higher wages, attract more skilled workers and invest more in training and research. Over time, that virtuous circle deepened the local pool of expertise and encouraged further innovation, from electrification to modern manufacturing and services. The new study’s authors argue that this cumulative process helps explain why the wage and innovation gaps tied to nineteenth century steam adoption have not closed, despite decades of national policy aimed at regional convergence.

For modern policymakers, the message is sobering. Lessons for Modern Policymakers Sascha Becker, the project lead at RFBerlin, has emphasised that the steam engine helped trigger a self reinforcing process of change that is difficult to reverse once it is under way. In his view, the historical record suggests that governments need to pay close attention to where new general purpose technologies take root, and to support lagging regions early if they want to avoid locking in another century of divergence. That argument is grounded in the study’s finding that the original industrial shock still shapes today’s map of change in wages and innovation.

What the steam legacy means for the next tech wave

The persistence of these gaps matters far beyond economic history seminars. As Germany and other advanced economies grapple with digitalisation, artificial intelligence and the green transition, the steam story offers a cautionary template. The study shows that, even 150 years after the first boilers fired up, the imprint of that technology is still visible in the distribution of high paying jobs and innovative firms. In other words, the geography of the next technological revolution is likely to be just as sticky as the last, unless policy intervenes early and decisively.

That is why the researchers stress the importance of understanding how past technologies reshaped regional fortunes. The fact that Steam power still helps explain modern German wage and innovation disparities suggests that new general purpose technologies could entrench today’s divides between thriving metropolitan regions and struggling industrial peripheries. For a country that prides itself on social cohesion, and for a world wrestling with the uneven impacts of technological change, that is a reminder that the real work begins long before the machines arrive.