Astronomers have, for the first time, weighed a planet that drifts through space without a parent star, turning a long standing theoretical curiosity into a precisely measured world. The lonely object is roughly the heft of Saturn and sits thousands of light years away, yet its gravity has given researchers a surprisingly sharp handle on both its mass and distance. The result opens a new window on how planets form, evolve and sometimes get violently kicked out of their home systems.

Instead of glowing on its own, this planet revealed itself only when it briefly warped the light of a more distant star, a fleeting alignment predicted by Einstein’s theory of gravity. By catching that distortion from multiple vantage points, scientists could finally pin down the properties of a truly free floating planet, rather than just guessing from models or indirect hints.

Weighing a world that has no sun

The newly characterized object belongs to a class known as rogue planets, worlds that wander the galaxy unbound to any star and that, as one summary notes, emit no light and do not interact with a parent star. I find that distinction crucial, because it explains why these planets have remained so elusive: without starlight to reflect or heat to radiate, they are effectively invisible except through their gravitational pull. In this case, that pull briefly magnified a background star in the dense central region of the Milky Way, creating a textbook example of gravitational microlensing.

Researchers tracked the event from the ground and from space, combining what one report describes as Joint ground and space based observations to measure how the apparent position and brightness of the background star shifted over time. By modeling that distortion, they could infer the size of the so called Einstein ring, the circular region where light is bent most strongly, and then use parallax between observatories to disentangle the planet’s mass from its distance. According to a detailed technical account, Using the parallax and the size of the Einstein ring showed that the lensing body is roughly Saturn sized and almost certainly lacks any stellar companion.

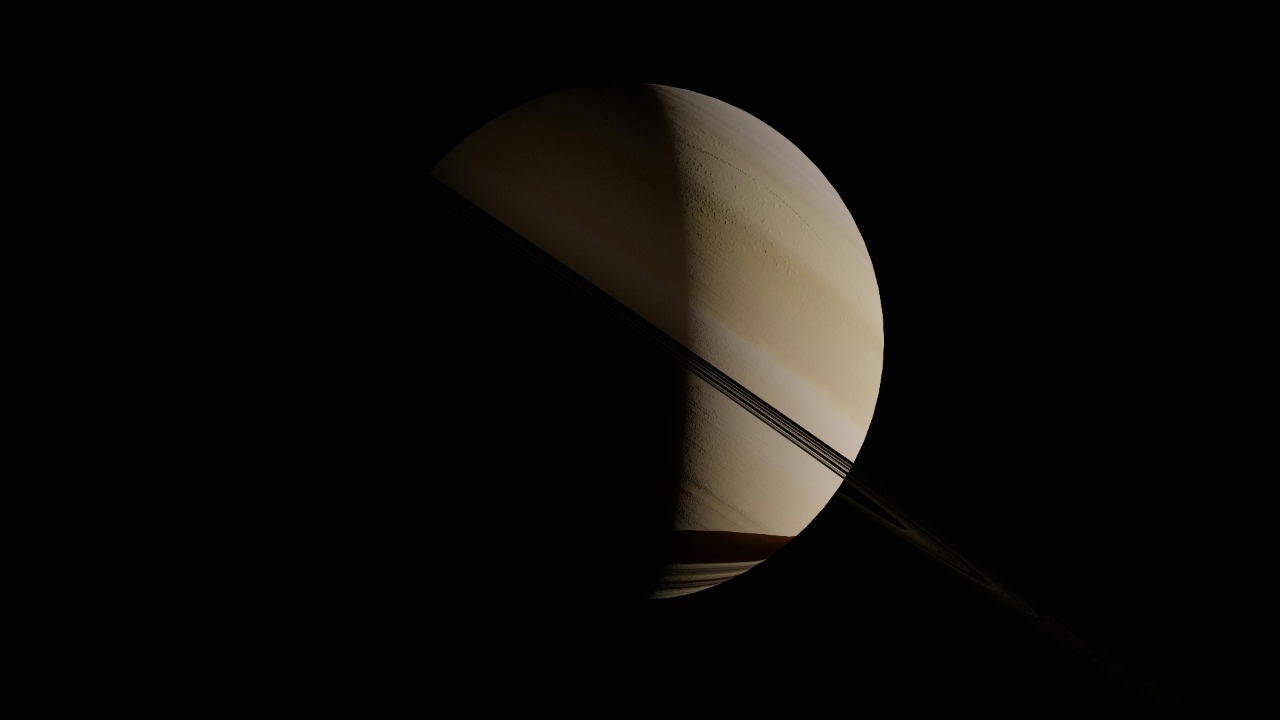

A Saturn mass exile in the Milky Way

The planet itself is a strikingly specific find, not just a vague dark mass. Multiple analyses converge on a world that is about 22 percent the mass of Jupiter, essentially a Saturn twin in terms of heft. One overview notes that The object is about 22 percent of Jupiter’s mass, while another emphasizes that the team has estimated the planet to be roughly a Saturn sized world, about 22 percent the mass of Jupiter, so roughly a Saturn sized world. That consistency matters, because it shows that independent modeling of the same microlensing signal is yielding the same physical picture.

Distance estimates are similarly tight. One social media summary explains that the object is designated OGLE 2024 BLG 0516 / KMT 2024 BLG 0792 and lies roughly 9,800 to 10,000 light years away in the galaxy’s bulge, a range echoed in other coverage that places the planet at 9,800 light years away. A separate report on the same event describes a newly discovered rogue planet flying alone through the Milky Way at approximately 10,000 light years away, a phrasing that lines up neatly with the 9,800 to 10,000 light year bracket. Taken together, these numbers give us a remarkably concrete sense of a starless planet’s place in the Milky Way.

From theoretical oddity to a new class of worlds

For years, rogue planets were mostly treated as statistical predictions, inferred from models of how often giant planets should be ejected from young systems. I see this measurement as the moment that population begins to solidify into a catalog of individual, well described worlds. One analysis even frames the result as part of a broader shift in which Polish scientists, working with European space data, are helping define a new class of planet by using bending starlight to probe how planetary systems form and evolve. That language underscores how a single well measured object can stand in for an entire hidden population.

The technical achievement is also a milestone for microlensing itself. A detailed breakdown notes that Rogue planets, which are free floating and lack a host star, are detected through gravitational microlensing, but until now their masses were hard to pin down. Here, careful modeling of the light curve allowed scientists to claim what one piece calls a Rare Saturn sized planet as the first free floating world with a precisely measured mass. Another account stresses that Astronomers have confirmed for the first time with direct evidence that a lone, starless world is actually drifting through the galaxy, while a complementary summary highlights that the mass and distance of a solitary rogue planet has been measured in a way that suggests it was thrown into interstellar space. In my view, that combination of dynamical history and precise weighing turns a once hypothetical exile into a real, physical world we can start to compare with the familiar planets orbiting our own Sun.