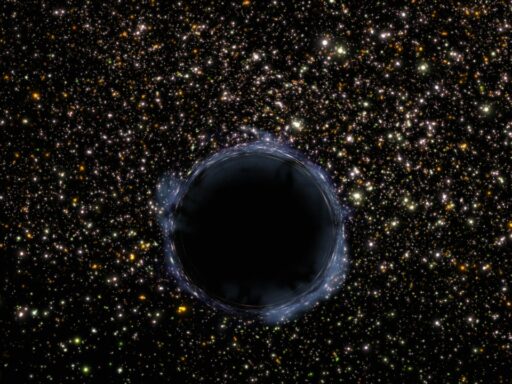

Astronomers have identified a seemingly ordinary star locked in a tight orbit around a dormant black hole, a pairing that challenges long‑held assumptions about how such systems form and survive. Instead of blazing with high‑energy fireworks, the black hole appears almost quiescent, forcing researchers to rethink how many similar dark companions might be hiding in plain sight across the Milky Way.

By tracking the star’s motion with precision instruments and cross‑checking its light with archival surveys, the discovery team pieced together a portrait of a “rule‑breaker” system that does not fit standard models of stellar evolution. I see it as an early glimpse of a much larger, largely invisible population of quiet black holes that could reshape how we map our own galaxy.

What makes this black hole–star duo so unusual

The standout feature of the newly reported system is not the black hole itself but the way it behaves, or rather, how little it seems to do. In most textbook examples, a stellar‑mass black hole in a close binary tears gas from its companion, heats that material in a bright accretion disk, and lights up X‑ray telescopes. Here, the companion star orbits a compact object with the mass and gravitational pull expected of a black hole, yet the system is remarkably faint in high‑energy bands, indicating that almost no matter is being siphoned off the star’s surface. That mismatch between a tight orbit and a quiet accretor is what makes this pairing so striking compared with previously cataloged binaries that blaze as X‑ray sources.

On top of the low‑energy output, the star’s orbit appears unusually circular and stable, which is not what I would expect if the black hole had formed in a violent supernova that kicked the system around. Standard models predict that when a massive star collapses, the explosion and any asymmetric “natal kick” should either disrupt the binary or leave behind a highly elongated orbit. Instead, the measured radial velocities and orbital period point to a configuration that looks almost undisturbed, a pattern that echoes earlier hints from other Gaia‑identified black hole candidates where the companion’s motion suggests a heavy, dark partner but little sign of past chaos.

How astronomers spotted a dark companion hiding in plain sight

Finding a black hole that barely interacts with its environment requires a very different strategy from hunting bright X‑ray binaries, and that is where precision stellar surveys come in. The team first flagged the star because its spectrum showed periodic Doppler shifts, a telltale sign that it was orbiting an unseen companion with substantial mass. By combining repeated spectroscopic measurements with distance and brightness data from large sky catalogs, they could infer the mass of the invisible object and rule out alternatives such as a white dwarf or neutron star. This approach mirrors the way exoplanets are found through stellar “wobbles,” but here the amplitude of the motion pointed to something far heavier than any planet, consistent with a stellar‑mass black hole.

Once the orbital solution was in hand, the researchers turned to X‑ray and radio archives to check whether the system had ever flared, which would betray active accretion. The absence of strong detections in those bands, even when the star was at orbital phases where mass transfer would be most likely, strengthened the case that the black hole is effectively dormant. Similar cross‑checks have been crucial in other recent discoveries of “silent” black holes, including systems where archival X‑ray limits helped confirm that the unseen companion was not a typical bright binary. I see this multi‑wavelength, data‑mining strategy as a template for uncovering many more such hidden objects.

Why the system breaks the usual rules of black hole formation

What really unsettles existing theory is how this system appears to have survived the birth of the black hole without being torn apart or dramatically reshaped. In conventional scenarios, a massive progenitor star ends its life in a core‑collapse supernova that ejects a large fraction of its mass and can impart a strong kick to the remnant. Losing that much mass in a sudden blast typically widens or unbinds a binary, while any kick tends to pump up orbital eccentricity. The nearly circular orbit inferred for this star suggests a very different pathway, one in which the black hole may have formed through a relatively gentle collapse with little mass ejection, a possibility that has been raised in earlier analyses of direct‑collapse candidates in the Milky Way.

There is also a tension between the star’s current properties and the evolutionary tracks that would normally lead to a black hole companion. The companion’s mass, temperature, and chemical makeup do not line up neatly with models where two massive stars evolve together, exchange mass, and then leave behind a compact remnant. Instead, the data hint that the black hole’s progenitor may have collapsed quietly while still retaining much of its envelope, or that the system underwent an atypical mass‑transfer history that avoided the dramatic common‑envelope phase predicted in many binary evolution models. I read this as a sign that our theoretical playbook for how close black hole binaries form is still missing key chapters.

What a quiet black hole reveals about the Milky Way’s dark population

If one relatively nearby star can hide a massive dark partner so effectively, it raises an obvious implication: the Milky Way may be teeming with similar systems that current surveys barely touch. Population studies already suggest that our galaxy should host tens of millions of stellar‑mass black holes, yet only a small fraction have been identified through bright accretion or gravitational waves. The new system fits into a growing class of “non‑interacting” binaries where the black hole’s presence is betrayed only by the companion’s motion, as seen in earlier candidates flagged by Gaia radial‑velocity data and follow‑up spectroscopy. Each such discovery helps bridge the gap between theoretical counts and observed objects.

These quiet binaries also matter for understanding the sources that gravitational‑wave detectors pick up. Mergers observed by facilities like LIGO and Virgo point to black hole pairs with specific mass ranges and spin properties, and one open question is how many of those systems started life in binaries with normal stars before evolving into double black holes. A population of wide, low‑accretion systems like the newly reported one could represent an intermediate stage in that journey, especially if later interactions or dynamical encounters tighten their orbits. By anchoring models of black hole population synthesis to real, quiescent binaries in the Milky Way, astronomers can better connect local observations to the distant mergers that ripple space‑time.

How future surveys could uncover many more “rule‑breakers”

The discovery underscores how much of the black hole census now depends on large, precise, and patient surveys rather than dramatic outbursts. I expect upcoming data releases from missions like Gaia, combined with ground‑based spectroscopic campaigns, to multiply the number of candidate systems where a seemingly ordinary star betrays a heavy, unseen partner. Techniques that search for subtle periodic shifts in stellar spectra, refined by machine‑learning tools trained on known binaries, are already being tested on massive datasets, as highlighted in recent work on machine‑learning binary searches. Each incremental improvement in velocity precision or time coverage makes it easier to spot the gravitational tug of a hidden black hole.

At the same time, deeper X‑ray and radio surveys will help separate true dormant black holes from other exotic companions. Sensitive instruments can place strict upper limits on any accretion‑powered emission, confirming that some systems are genuinely quiet rather than simply caught in a temporary lull. When those constraints are combined with detailed modeling of the companion star’s wind and rotation, researchers can estimate how much material should be available for accretion and why it might be suppressed. That kind of multi‑pronged analysis, already demonstrated in studies of quiescent binary systems, will be essential for turning one “rule‑breaking” discovery into a statistically robust map of the Milky Way’s hidden black hole population.