Far from being solid cannonballs, many asteroids are fragile heaps of debris spinning through space on the edge of structural failure. When one of these objects rotates too quickly, the outward pull at its surface can rival or exceed its own weak gravity, setting the stage for landslides, mass shedding, or full breakup. Astronomers now see that some space rocks are rotating so rapidly that they are effectively stress testing the limits of what a small world can survive.

The stakes are not abstract. Fast rotators help explain why so many asteroids are binaries, why some suddenly sprout dusty tails, and how planetary building blocks were ground down over time. They also shape how I think about ambitious concepts like hanging skyscrapers from orbiting rocks, which would have to contend with the same centrifugal forces that threaten to rip unstable asteroids apart.

How fast is too fast for a rubble pile?

For decades, researchers assumed most asteroids were solid monoliths, but detailed observations now show that Earth-crossing fragments and main belt objects alike are often “rubble piles,” loose clusters of rock held together mainly by self gravity. In that regime, there is a practical spin barrier: once an object larger than about 150 m across rotates faster than a few hours per turn, centrifugal acceleration at its equator can rival its surface gravity. That balance is captured in the same basic physics used for artificial habitats, where the inward pull must exceed the outward spin so people, or boulders, do not fly off. In textbook form, the radial acceleration is written as Alternatively \(a_c = R \cdot \omega^2\), which grows with both radius and spin rate.

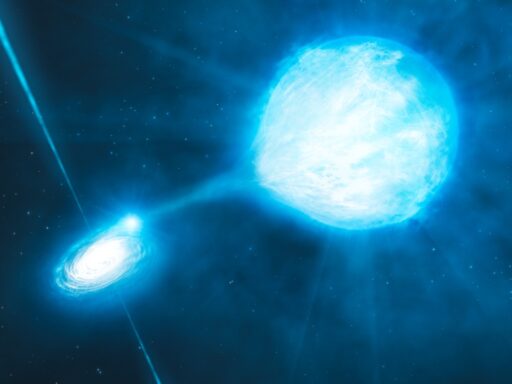

In a self-gravitating body, the inward pull is set by its mass and size, with Gravitational Acceleration \(g = GM/r^2\), where G is the same constant that appears in models of collapsing stars, such as simulations in which The constant G defines the self gravity of matter. At an asteroid’s fringe, as one astrophysical treatment puts it, Near the edge the outward centrifugal push can exceed the inward pull, allowing material to migrate or escape. That same balance governs whether a spinning asteroid holds together or begins to shed mass into space.

Sunlight, YORP, and the slow spin toward disaster

The surprising driver behind many of these extreme spin rates is not a collision but sunlight itself. When irregularly shaped bodies absorb and re-emit solar energy, they experience tiny torques collectively known as the Yarkovsky–O’Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack effect, or YORP. As one review notes, When smaller asteroids are heated by the Sun, they eventually reradiate that energy in the thermal band and in scattered sunlight, which can modify the rotation. In some cases, the effect is strong enough that Direct measurements of objects like Bennu show that YORP torques could double their spin rate over hundreds of thousands of years if sustained.

The cumulative impact is dramatic. One theoretical study finds that The YORP effect can destroy hypothetical Vulcanoids by spinning them up so fast that gravity can no longer hold their components together, forcing them to rotationally fission. A broader population model concludes that Conclusions The YORP induced rotational fission hypothesis can explain the primary formation mechanism of many binary asteroids. Observationally, A number of young asteroid pairs in the main belt appear to have been created by exactly this kind of spin-driven breakup.

When spinning rocks actually start to fall apart

Once an asteroid approaches its critical rotation rate, its surface can begin to rearrange. Detailed simulations show that Rubble pile asteroids are generically capable of reshaping, undergoing piece wise mass loss, and forming satellites as they spin up. If astronomers catch such a body in the act of shedding material, Jewitt and colleagues describe it as an active asteroid, a category that can evolve into long term stable systems. Fragment tracking around one such object, 331P/Gibbs, shows that The results are consistent with rotational disruption driven by the rapid rotation of the primary.

We see related behavior in better known targets. Asteroid Bennu, a potentially hazardous near Earth object visited by NASA’s OSIRIS mission, is a classic top shaped rubble pile, and surface changes on Bennu, including a landslide and crater from a small impactor, give scientists better insight into how rubble-pile asteroids held together by gravity take a hit. Another sample return target, Ryugu (162173 Ryugu), is not a single chunk of its parent. Instead, it is a rubble pile asteroid, a collection of debris reassembled into Ryugu after earlier destruction. These case studies show that rotational reshaping is not theoretical, it is written into the geology of the best explored small bodies in the Solar System.

Record-breaking rotators and what they tell us

Some asteroids push the spin barrier to extremes. Observations of New Large Super fast rotators like (335433) 2005 UW163 show that objects larger than 150 m can rotate in less than an hour, which challenges simple rubble pile assumptions and hints at internal strength. Pre survey data from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory reveal that Most asteroids are rubble piles, which limits how fast they can spin without breaking apart, so any large body rotating faster than that limit is immediately interesting. A recent close approach by a compact, rapidly rotating near Earth object underscored that Asteroids are not just drifting rocks but dancers in space, with sunlight as their choreographer.

Smaller bodies show how this process can sculpt entire systems. In the inner Solar System, Asteroids with diameters less than approximately 10 km are subject to spin up by the YORP effect, and rapid spin of the small body Dinkinesh appears to have created a contact binary satellite and a trough on its surface. Many tiny objects end up with moons because Asteroids can spin quickly enough to shoot away rocks that then go into orbit. In some cases, the binary YORP effect, in which Sunlight hits both members of a pair, can further evolve their orbits and spins.

From theory to planetary defense and wild engineering ideas

Understanding how and when a spinning asteroid fails is not just an academic exercise. Planetary defense tests, such as the DART impact on Dimorphos, revealed that Finally, Colas Robin SUPAERO in France compared the surface boulders of Dimorphos to those of asteroids Itokawa and concluded that Dimorphos is likely a rubble pile rather than a more solid single mass. That matters because the same impact energy will produce very different outcomes in a cohesive rock versus a loosely bound aggregate. In the main belt, (1) where m is the mass of the asteroid enters into models of chaotic diffusion from close encounters, which in turn depend on how easily those bodies can be disturbed or reshaped.

The same physics also constrains speculative megastructures. A viral skyscraper concept imagined suspending a tower from an orbiting rock tens of thousands of kilometers above Earth, but critics noted that When the height of that tower reaches that altitude, the rotational speed would increase exponentially and tear it apart. The same logic applies to natural systems: if a rubble pile is elongated or develops a tall equatorial ridge, the outermost material feels the greatest centrifugal stress. In a broader celestial context, even free floating worlds remind us that Celestial bodies cannot self generate rotational forces, Jared, so any spin that threatens to unmake an asteroid is the fossil record of past gravitational nudges and long term solar torques.

Even the fine details of how heat is emitted matter. When the shape of the asteroid is very irregular, When the heat is not radiated evenly, it creates a tiny but continuous thrust that can accelerate the rate at which Itokawa spins. In detailed rotational models, parameters like the obliquity of the spin axis γ and the radius R, where where γ represents the obliquity and R is the asteroid radius given in metres, control how these torques evolve. As I weigh all of this evidence, from active asteroids like 2010A2 Linear, where Thi short lived tail was linked to dust release, to the observation that Most small bodies are rubble piles, the picture that emerges is of a Solar System where many asteroids are indeed spinning so fast that, given enough time, they will tear themselves apart.