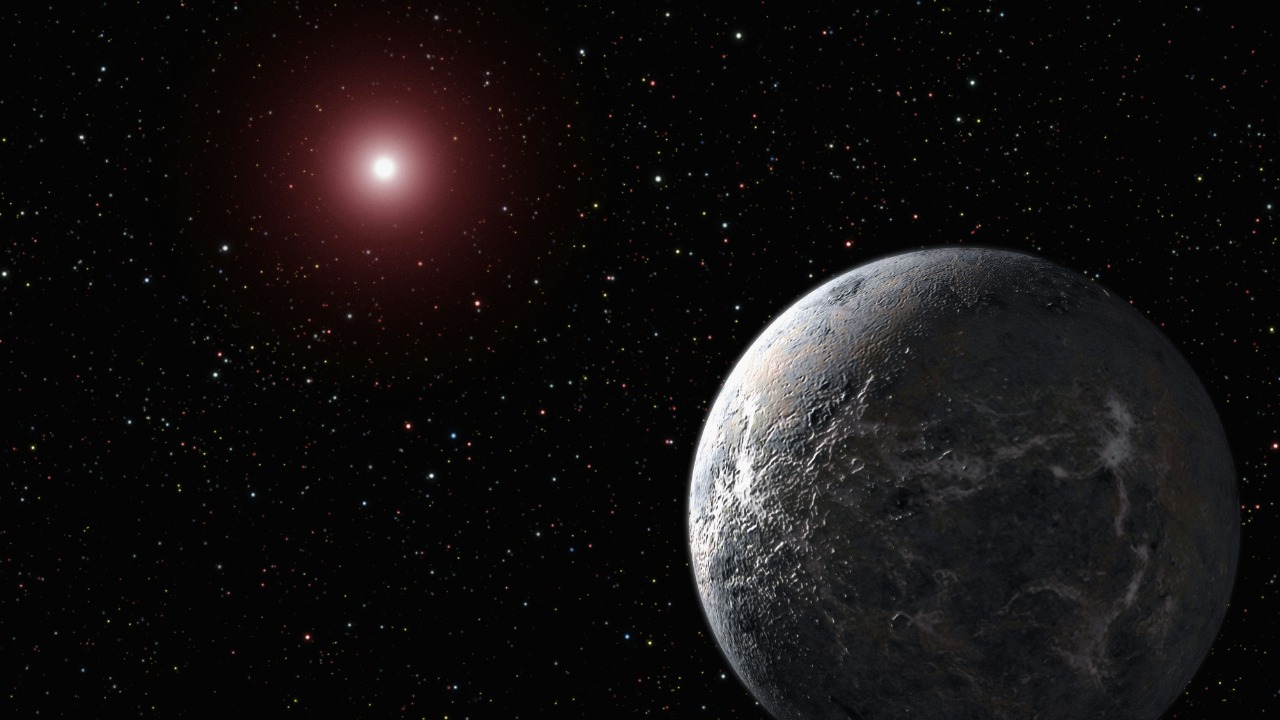

Astronomers have identified a rare free‑floating exoplanet drifting roughly 10,000 light‑years from Earth, a lonely world that travels without the warmth or light of a parent star. The object, comparable in size to Saturn, is the first of its kind whose mass and distance have been pinned down with precision, turning a once purely theoretical population of “starless” planets into a measurable reality. Its discovery opens a new window on how planetary systems form, evolve and sometimes violently eject their worlds into interstellar space.

Unlike the thousands of exoplanets found orbiting nearby stars, this body reveals itself only through its gravity, briefly magnifying the light of a more distant star as it passes in front. By catching that fleeting brightening and modeling it in detail, researchers have been able to weigh the planet, place it at about 9,950 light‑years away and show that it roams the Milky Way alone. For planetary science, that combination of isolation and precision makes this object a crucial test case rather than just another exotic outlier.

What makes this rogue planet so rare

Rogue planets, sometimes called homeless or starless worlds, are thought to be common in the Milky Way, but they are almost invisible because they do not shine and do not reflect a nearby star. In this case, Jan and other Astronomers caught a brief gravitational microlensing event, when the planet passed in front of a distant background star and its gravity temporarily bent and amplified the starlight. That subtle brightening, seen from roughly 10,000 light‑years away, revealed a Saturn‑scale object drifting alone through the Rogue planets population that had previously been inferred mostly from theory.

Follow‑up analysis showed that the lensing signal could not be explained by a star or brown dwarf, but instead matched a Saturn‑sized planet with no detectable host star within a vast radius. By carefully modeling how long the brightening lasted and how sharply it peaked, researchers concluded that the object sits about 9,950 light‑years from Earth, near the crowded central regions of our galaxy. That distance estimate, combined with the lensing strength, allowed them to calculate the planet’s mass with unusual accuracy for such a faint and distant target.

First precise mass and distance for a starless world

What elevates this discovery from curiosity to milestone is that it is the first rogue planet for which both mass and distance have been measured precisely. Jan and colleagues used the shape of the microlensing light curve, along with the relative motion of Earth and the background star, to break the usual degeneracies that plague such measurements. As one analysis put it, This is the first rogue planet whose basic physical properties are pinned down well enough to compare directly with planets bound to stars.

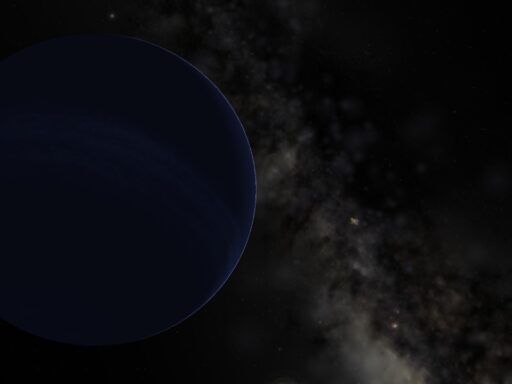

The team’s modeling indicates a Saturn‑like mass, which aligns with earlier hints that free‑floating planets might span a wide range of sizes, from smaller than Earth to objects approaching the threshold of brown dwarfs. In this case, the object fits squarely into the category of a Rare Saturn sized rogue planet, confirming that full‑scale gas giants can survive ejection from their birth systems and continue to wander interstellar space for billions of years. That finding strengthens the idea that violent gravitational interactions in young planetary systems can fling out large worlds, not just small rocky bodies.

Clues to how planetary systems form and fall apart

For me, the most intriguing aspect of this discovery is what it implies about the hidden architecture of planetary systems across the galaxy. If a Saturn‑mass planet can be kicked out into the dark, then the early history of many systems must be far more chaotic than the relatively orderly layout of our own suggests. Jan and other researchers argue that such ejections likely happen when giant planets migrate inward or scatter off each other, leaving some worlds bound and others exiled into the galactic field. The new detection, which sits in the inner Milky Way, hints that these violent reshufflings may be especially common in the dense stellar environments near the centre of our galaxy.

The technique that revealed this planet also points to a vast, unseen population of similar objects. A lucky alignment of the planet, a background star and Earth produced the microlensing signal, but such alignments are rare and brief, which means each detection likely represents many more missed events. Jan and other Astronomers suggest that there could be billions or even trillions of such bodies drifting through the Milky Way with no Sun of their own, each one a fossil record of a planetary system that once was. As future surveys refine microlensing searches and space telescopes add sharper imaging, I expect this first precisely weighed rogue world to be joined by a catalog of starless planets that will force astronomers to rethink how common, and how fragile, planetary systems really are.