NASA’s Mariner 2 spacecraft made a historic flyby of Venus on Dec. 14, 1962, becoming the first successful robotic mission to another planet and returning unprecedented data on Earth’s nearest planetary neighbor. The Mariner 2 flyby of Venus marked a turning point in early space exploration by proving that interplanetary travel and close-up planetary science were possible with 1960s technology. I see that moment as a pivot from experimental rocketry to a sustained, data-driven exploration of the inner solar system.

Setting the stage for Mariner 2’s Venus encounter

NASA developed the Mariner 2 spacecraft specifically to attempt the first successful mission to another planet, designing it as a focused, relatively lightweight probe that could survive the harsh conditions of interplanetary space and still function near Venus. Engineers built Mariner 2 around a simple but robust bus, with solar panels, a high-gain antenna, and a compact suite of scientific instruments tuned to measure radiation, magnetic fields, and the thermal environment around the planet. By targeting Venus, Earth’s nearest planetary neighbor, mission planners chose a destination that was both scientifically compelling and technically reachable with the launch vehicles and navigation techniques available in the early 1960s, which made the stakes unusually high for both planetary science and national prestige.

The planned flyby of Venus by Mariner 2 fit squarely into the early 1960s race to explore the inner solar system, when the United States and the Soviet Union were each trying to claim firsts beyond Earth orbit. In that context, a successful encounter with another planet would demonstrate not only advanced rocketry but also precise trajectory design, deep-space communications, and long-duration spacecraft operations. I view this as the moment when planetary exploration shifted from theoretical calculations and ground-based telescopes to direct, in situ measurements that could confirm or overturn long-standing ideas about worlds like Venus, setting expectations for every inner solar system mission that followed.

Launch, journey, and approach to Venus

The Mariner 2 spacecraft traveled through interplanetary space for months before its close pass by Venus, following a carefully calculated trajectory that carried it away from Earth and into the planet’s orbital neighborhood. During that cruise, mission controllers had to maintain contact across increasing distances, monitor the health of the spacecraft’s systems, and adjust its course so that the instruments would be properly aligned during the encounter. The long, quiet stretch between launch and arrival tested the reliability of 1960s-era electronics in deep space and showed that a relatively small probe could operate autonomously for extended periods, a capability that remains central to every planetary mission today.

The mission timeline culminated when Mariner 2 flew by Venus on Dec. 14, 1962, after a long cruise from Earth that had been planned to bring the spacecraft within close range without requiring it to slow down or enter orbit. That flyby geometry allowed the probe to sweep past the planet, gather data during a brief but intense window of observation, and then continue on into solar orbit. I see that approach strategy as a template for later missions that used similar gravity-assist and flyby techniques, proving that meaningful planetary science did not require the far more complex and expensive step of going into orbit or landing on the first attempt.

Dec. 14, 1962: The historic Venus flyby

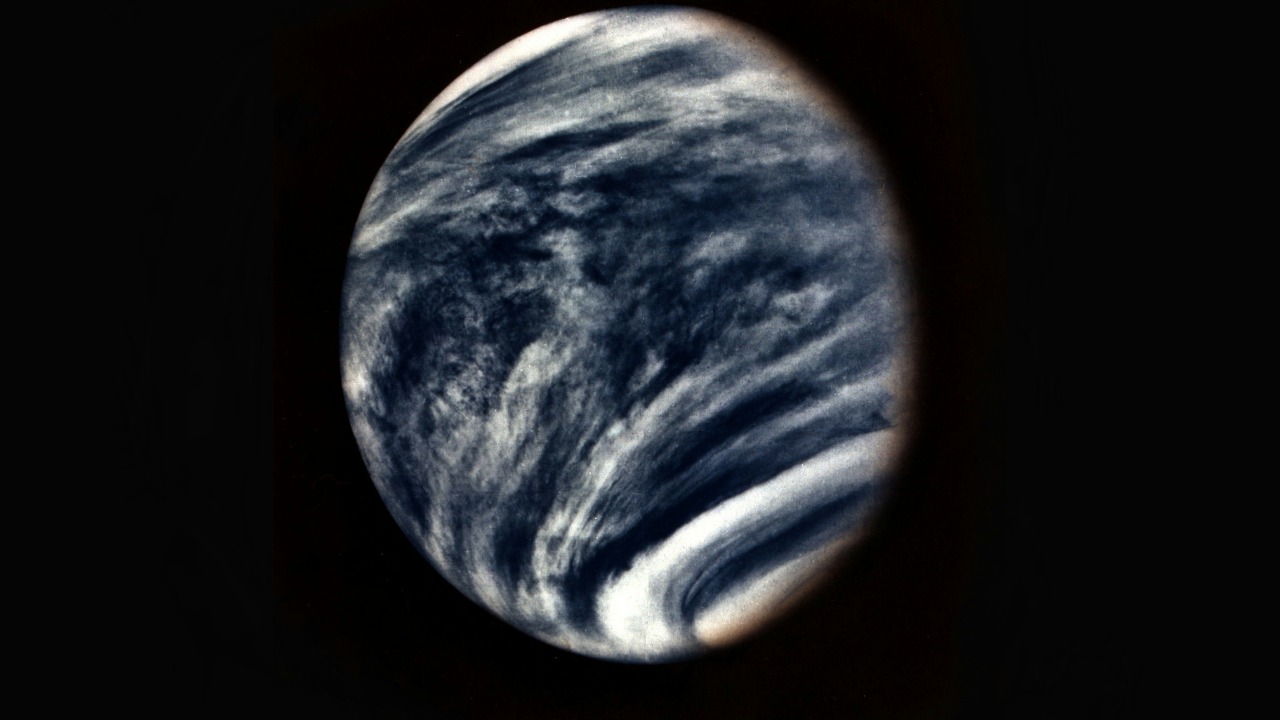

NASA’s Mariner 2 spacecraft flew by Venus on Dec. 14, 1962, collecting scientific measurements during its closest approach as its instruments scanned the planet and its surrounding environment. During that critical period, the probe’s sensors recorded how radiation, temperature, and other physical conditions changed as it passed near the shrouded world, transmitting those readings back to Earth through its high-gain antenna. The encounter transformed Venus from a distant, cloud-covered disk into a measurable physical system, and I see that as the moment when planetary flybys proved their value as efficient, high-impact scientific tools.

The Dec. 14 Mariner 2 flyby of Venus represented the first time a spacecraft successfully visited another planet, a milestone that immediately redefined what was considered technically achievable in space exploration. By surviving launch, enduring months in deep space, and operating as planned during the flyby, Mariner 2 validated the concept of robotic planetary missions at a time when even reaching orbit had only recently become routine. That success raised expectations for future probes to Mars, Mercury, and beyond, and it signaled to scientists and policymakers that targeted, relatively low-mass spacecraft could deliver transformative results without the cost and risk of crewed interplanetary travel.

Scientific discoveries from Mariner 2’s Venus data

Instruments on the Mariner 2 spacecraft gathered data that transformed scientists’ understanding of Venus’s environment, replacing earlier, more speculative ideas with direct measurements. Before the flyby, some researchers still entertained the possibility of a temperate surface hidden beneath the clouds, but the spacecraft’s thermal and radiometric readings showed that Venus is an extremely hot world with a dense atmosphere that traps heat. Those findings, drawn from the probe’s carefully calibrated sensors, helped establish Venus as a prime example of a runaway greenhouse effect, and I see that as a foundational result that continues to inform how scientists think about planetary climates, including Earth’s.

The Mariner 2 flyby of Venus provided direct measurements that replaced earlier, more speculative ideas about the planet, giving researchers hard numbers on conditions that had previously been inferred only from telescopic observations and theoretical models. By quantifying the planet’s thermal environment and sampling the space around it, the mission clarified how Venus interacts with the solar wind and how its thick atmosphere shapes the conditions near the surface. Those data points became benchmarks for later missions and models, and in my view they turned Venus from a largely hypothetical world into a well-characterized target whose extreme conditions could be studied systematically rather than guessed at from afar.

Legacy and “On this day in space” remembrance

The anniversary segment “OTD in Space – December 14: Mariner 2 Spacecraft Flies by Venus” connects that 1962 flyby to ongoing efforts to commemorate key milestones in planetary exploration, highlighting how a single mission can reshape scientific priorities for decades. By revisiting the details of the encounter and the data it returned, such retrospectives keep the technical and scientific achievements of Mariner 2 in the public eye, reminding audiences that today’s missions to Venus and other planets build directly on those early successes. I see these commemorations as a way to link current debates over where to send new probes with the historical record of what has already been learned, grounding future plans in proven accomplishments.

Historical retrospectives like “Dec. 14, 1961: Mariner 2 flies by Venus” underline how this single flyby continues to shape how space missions to Venus and other planets are planned today, from instrument selection to trajectory design. By tracing how Mariner 2’s measurements redefined Venus and validated long-distance spacecraft operations, these accounts show why mission planners still look back to that encounter when justifying new proposals and refining risk assessments. I regard that legacy as a reminder that each successful planetary mission does more than answer immediate scientific questions, it also sets technical standards and strategic expectations that guide exploration across the solar system for generations.