Sam Altman is trying to convince the world that the future of AI hardware is not a screen you stare at, but an object you might literally put in your mouth. His teasing description of a Jony Ive–designed OpenAI gadget that can be licked is more than a quirky soundbite, it is a signal that the company wants to redefine how people physically experience artificial intelligence.

I see that provocation as part of a broader attempt to move AI out of the phone and into the fabric of everyday life, using industrial design and sensory interaction to make machine intelligence feel less like software and more like a companion. The question is whether this strange new device will be a serious computing platform or a beautifully crafted novelty.

Altman’s “lickable” teaser and what it really signals

Altman’s remark that the OpenAI hardware project involves something you can lick is not just a joke about taste, it is a deliberate way of framing the device as intimate, tactile and always within reach. By invoking the idea of putting the product in a user’s mouth, he is hinting at a form factor closer to jewelry, a wearable or a personal token than a traditional gadget, a move that aligns with his broader push to make AI feel less like a tool and more like a presence in a user’s life, as he has suggested in earlier discussions of personal AI assistants and dedicated devices that live with you all day rather than waiting behind an app icon on a phone screen, a vision that has been described in coverage of his hardware ambitions in partnership with Jony Ive and SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son in reports on an AI-first device.

That framing also helps OpenAI differentiate its hardware effort from the wave of AI wearables that have already reached the market, such as the Humane AI Pin and the Rabbit R1, which rely on cameras, microphones and voice rather than any kind of direct bodily contact, and which have been criticized in detailed reviews for awkward ergonomics, laggy responses and unclear use cases, as seen in assessments of the Humane AI Pin and the Rabbit R1. By leaning into a provocative sensory metaphor at the concept stage, Altman is effectively promising that OpenAI’s device will not be just another clip-on microphone for ChatGPT, but a rethinking of how close a user can get to an AI system, even if the exact hardware design remains unverified based on available sources.

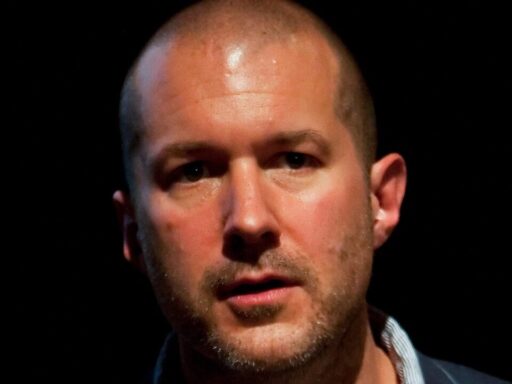

Jony Ive’s design playbook meets OpenAI’s ambitions

Bringing Jony Ive into the project signals that OpenAI is not content with a utilitarian reference design, it wants an object that can stand alongside the most iconic consumer hardware of the last three decades. Ive’s track record at Apple, from the original iMac and iPod to the iPhone and Apple Watch, shows a consistent pattern of turning complex technology into approachable, almost jewelry-like artifacts that invite touch and daily use, a pattern documented in retrospectives on his role in shaping products like the iPhone and Apple Watch. When I hear Altman talk about a device that could be licked, I read it as an extension of Ive’s obsession with materials, edges and surfaces that feel so carefully finished that users instinctively want to handle them, whether that means the polished aluminum of a MacBook or the ceramic back of an Apple Watch Edition.

Ive’s post-Apple studio, LoveFrom, has already taken on projects that blend high design with emerging technology, including collaborations with brands that want to signal a premium, almost timeless aesthetic rather than a disposable gadget culture, as noted in coverage of his work with partners like Airbnb and Ferrari. Plugging that design philosophy into OpenAI’s hardware push suggests the company is aiming for a device that feels more like a personal object than a miniaturized computer, something that could sit on a bedside table or be worn on the body without screaming “tech product.” The challenge, which Ive has faced before with the first Apple Watch and the controversial “trash can” Mac Pro, is to ensure that the pursuit of beauty and novelty does not compromise practicality, a tension that past product histories have laid out in detail in analyses of his more polarizing designs such as the 2013 Mac Pro.

Why OpenAI wants its own hardware at all

OpenAI’s move into hardware is not happening in a vacuum, it is a strategic response to the limits of living entirely inside other companies’ platforms. Today, most people experience ChatGPT and related models through a web browser, a mobile app or integrations inside products like Microsoft’s Copilot, which gives OpenAI reach but also means it is always one layer removed from the user’s primary device, a dynamic described in reporting on its deep partnership with Microsoft. By creating its own physical product, OpenAI can control the full stack from silicon and sensors up through the AI model and user interface, a level of integration that companies like Apple and Google have long used to differentiate their ecosystems.

There is also a business logic to owning the hardware channel, especially as OpenAI rolls out more capable and more expensive models such as GPT-4 and GPT-4o, which require significant compute resources and benefit from predictable usage patterns. A dedicated device can be tuned to specific interaction modes, such as short spoken queries or ambient monitoring, which in turn can help OpenAI optimize inference costs and potentially bundle subscriptions, as analysts have suggested in coverage of its evolving revenue model. If the company can convince users to adopt a bespoke gadget as their primary interface to its AI, it gains not only brand visibility but also a direct line for data collection, feedback and feature experimentation that is harder to achieve when it is just another app on a crowded home screen.

The crowded field of AI gadgets and what went wrong

Any new OpenAI device will enter a market already littered with cautionary tales, and the most instructive examples are the Humane AI Pin and the Rabbit R1. Both products promised a future where users could offload tasks to an AI assistant that lives on the body or in the pocket, yet early reviews highlighted slow responses, unreliable recognition and confusing value propositions, with one detailed evaluation of the Humane AI Pin describing frequent misfires and heat issues, and another of the Rabbit R1 noting that it often performed worse than simply using a smartphone. These failures underscore a hard truth: wrapping a large language model in novel hardware does not automatically create a compelling product if the underlying experience is not faster, easier or more delightful than existing devices.

For OpenAI and Ive, the lesson is that industrial design and AI capability must be tightly aligned with clear, everyday use cases, not just speculative demos. The Humane AI Pin struggled with battery life and thermal constraints because it tried to be a general-purpose assistant always listening and projecting information, while the Rabbit R1 leaned on a “large action model” to control apps on a user’s behalf but ran into practical limitations when services changed their interfaces or required additional authentication, as reviewers documented in their breakdown of its app control features. If OpenAI’s device is going to avoid the same fate, it will need to define a narrower set of interactions where a dedicated object, perhaps one that is worn or handled in specific ways, truly outperforms a smartphone running the ChatGPT app.

From sensory gimmick to everyday companion

The idea of a lickable AI gadget risks being dismissed as a marketing stunt, but it also points to a deeper question about how people will physically relate to artificial intelligence in the next decade. A device that is meant to be touched, worn or even tasted suggests a level of intimacy that goes beyond smart speakers like Amazon Echo or Google Nest, which mostly sit on a shelf and wait for voice commands, and instead moves toward something closer to a digital talisman, a constant companion that users fidget with, consult and perhaps even find comfort in, a direction hinted at in analyses of how people bond with social robots and virtual agents. If OpenAI and Ive can translate that intimacy into a reliable, privacy-conscious product, they could help normalize AI as a personal presence rather than a distant cloud service.

At the same time, the sensory framing raises practical concerns about hygiene, durability and accessibility that any serious hardware team will have to address. A product that invites touch or contact with the mouth must be built from materials that can withstand repeated cleaning, avoid allergens and comply with safety regulations, constraints that medical device makers and wearable manufacturers know well from their work on products like Apple Watch bands and in-ear headphones. If the “you can lick it” line is ultimately metaphorical rather than literal, it still serves as a useful stress test for the design: can this object survive the messy realities of daily life, from pockets and purses to kids and pets, while maintaining the kind of premium feel and seamless AI performance that users now expect from top-tier consumer electronics?