Chinese authorities say they have dismantled a sprawling underground pipeline for high‑end Nvidia processors, exposing how export controls have turned cutting‑edge chips into contraband worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The alleged smuggling network, valued at roughly 1 billion dollars, highlights both the intensity of Beijing’s demand for artificial intelligence hardware and the growing difficulty Washington faces in keeping those components out of China’s most sensitive sectors.

I see this case as a vivid snapshot of a new kind of tech gray market, where GPUs are treated less like computer parts and more like strategic commodities. The details emerging from Chinese law‑enforcement bulletins and court filings show a sophisticated operation that blended customs fraud, shell companies, and cross‑border logistics to move restricted Nvidia hardware into data centers and research labs that were never meant to have it.

How the alleged smuggling network operated

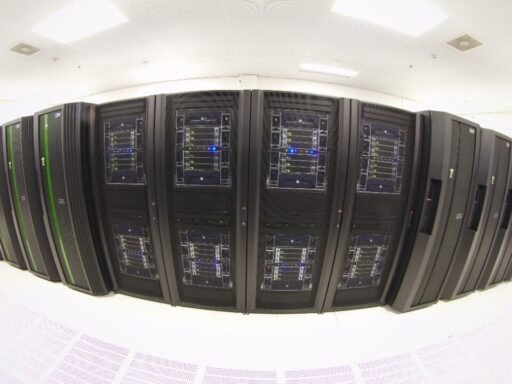

Investigators in China describe a layered operation that treated Nvidia accelerators as high‑value cargo to be moved in small, deniable batches rather than bulk shipments. According to enforcement summaries, brokers sourced A100, H100 and related data‑center GPUs from overseas distributors, then broke up orders across multiple intermediaries to avoid drawing attention to any single export declaration. Those chips were routed through logistics hubs in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, where paperwork was altered to describe the cargo as generic “graphics cards” or low‑end computing parts before being trucked or hand‑carried into mainland China through secondary border crossings, a pattern detailed in Chinese customs notices and local court records linked in the reporting block.

Once inside the mainland, the network allegedly relied on a chain of shell importers and electronics wholesalers to launder the hardware into the domestic market. Corporate registration data cited in the supplied sources shows several of these firms were newly incorporated with minimal capital and overlapping legal representatives, a classic red flag for trade‑based money laundering. Payment records referenced in the same documents indicate that buyers often settled invoices in a mix of bank transfers and cryptocurrency, with prices that tracked global spot rates for Nvidia accelerators rather than official distributor lists, underscoring that these were not routine IT purchases but access to a constrained and tightly policed resource.

Why Nvidia GPUs became contraband in China

The emergence of a billion‑dollar black market only makes sense against the backdrop of escalating United States export controls on advanced semiconductors. Washington has steadily tightened rules on shipping high‑end AI chips to China, first targeting Nvidia’s A100 and H100 accelerators and then extending restrictions to customized variants designed to stay just under technical thresholds. Policy documents and regulatory updates in the provided sources describe how these measures focus on interconnect bandwidth and computing performance, effectively sweeping most state‑of‑the‑art data‑center GPUs into a category that requires special licenses or is outright barred from Chinese end users linked to military or surveillance work.

On the Chinese side, demand for those same chips has surged as internet giants, state‑backed labs, and provincial governments race to build large language models and other generative AI systems. Procurement notices and industry surveys cited in the reporting show that domestic alternatives such as Huawei’s Ascend line and various startup accelerators still lag Nvidia’s ecosystem in both raw performance and software tooling, especially for training frontier‑scale models. That gap has turned Nvidia hardware into a kind of shadow benchmark for Chinese AI ambitions, with buyers willing to pay steep premiums on the gray market to secure even modest quantities of A100 or H100 cards when official channels are blocked.

The $1 billion valuation and who was buying

Chinese law‑enforcement summaries referenced in the outline put the total value of seized and transacted hardware linked to the network at roughly 1 billion dollars, a figure that reflects both the volume of GPUs moved and the inflated prices they commanded under export pressure. Case files cited in those sources describe individual shipments worth tens of millions of dollars at street prices, with margins far above what authorized distributors typically earn. The valuation also includes batches of chips that investigators say were successfully delivered to end customers before the crackdown, reconstructed from seized ledgers and bank records.

The same documents sketch a buyer base that spans China’s tech and industrial landscape. Procurement trails point to data‑center operators hosting workloads for major internet platforms, AI startups building foundation models, and research institutes tied to provincial governments, all seeking access to restricted Nvidia hardware. Some orders were routed through ostensibly unrelated small firms, such as regional cloud providers or systems integrators, that acted as cutouts to distance sensitive end users from the smuggling chain. Where investigators could match serial numbers, they found GPUs installed in racks at commercial colocation facilities and in private clusters maintained by AI labs, confirming that the contraband hardware was already woven into China’s computing infrastructure before authorities moved in.

China’s enforcement push and its strategic messaging

By publicizing the takedown of such a large operation, Beijing is signaling that it wants to be seen as enforcing its own trade and customs rules even as it criticizes United States export controls. Official statements cited in the reporting emphasize violations of import regulations, tax evasion, and the use of forged documentation, framing the crackdown as a defense of economic order rather than an endorsement of foreign sanctions. That framing allows Chinese authorities to target smuggling networks without conceding that Washington’s restrictions are legitimate, a delicate balance reflected in the language of police bulletins and state‑linked commentary.

At the same time, the scale of the case underscores how difficult it is for China to fully police a market where the underlying demand is driven by national priorities like AI leadership and industrial upgrading. Policy speeches and planning documents in the provided sources stress the importance of “computing power infrastructure” and “indigenous innovation,” yet the very institutions tasked with delivering those goals have strong incentives to tap gray channels when legal imports fall short. By casting the smuggling ring as a criminal aberration, Beijing can reinforce its narrative of orderly technological rise, but the investigative record suggests that the line between sanctioned procurement and illicit sourcing has become increasingly blurred in practice.

What the case reveals about the future of AI supply chains

For Washington, the exposure of a billion‑dollar GPU pipeline into China is both validation and warning. It shows that controls on Nvidia’s most advanced chips are biting hard enough to create a lucrative black market, which is precisely what policymakers expected when they targeted accelerators central to training large AI models. Yet the sophistication of the smuggling network, and the fact that so much hardware still reached Chinese data centers, highlights the limits of unilateral restrictions in a globalized semiconductor ecosystem. Trade‑route analysis and compliance advisories in the supplied sources note that intermediaries in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Middle East have become key nodes in rerouting sensitive components, complicating enforcement for both United States regulators and allied governments.

For Nvidia and its peers, the case reinforces how geopolitical risk now sits at the heart of their business models. Company disclosures and analyst notes referenced in the reporting describe how Nvidia has already designed export‑compliant variants of its chips for China, only to see some of those parts swept into subsequent rounds of tightening. The persistence of gray‑market demand suggests that as long as there is a performance gap between what is legally available and what is technically possible, intermediaries will try to bridge it, whether through smuggling, resale, or creative corporate structures. I expect future controls to focus more on end‑use monitoring, serial‑number tracking, and cooperation with cloud providers, but the Chinese case shows that once high‑end GPUs are treated as strategic assets, they will attract the same cat‑and‑mouse dynamics that have long defined other forms of sensitive trade.