Ancient Chinese texts, dating back over 2,000 years, contain detailed records of solar eclipses that modern scientists are using to refine our understanding of Earth’s rotation and historical timekeeping. A recent study analyzing these ancient observations has revealed discrepancies in eclipse timings that challenge previous models of axial precession and tidal friction effects on the planet’s spin. This breakthrough, highlighted in contemporary astronomical research, underscores how forgotten historical data can illuminate ongoing debates in geophysics and cosmology.

Ancient Chinese Eclipse Records

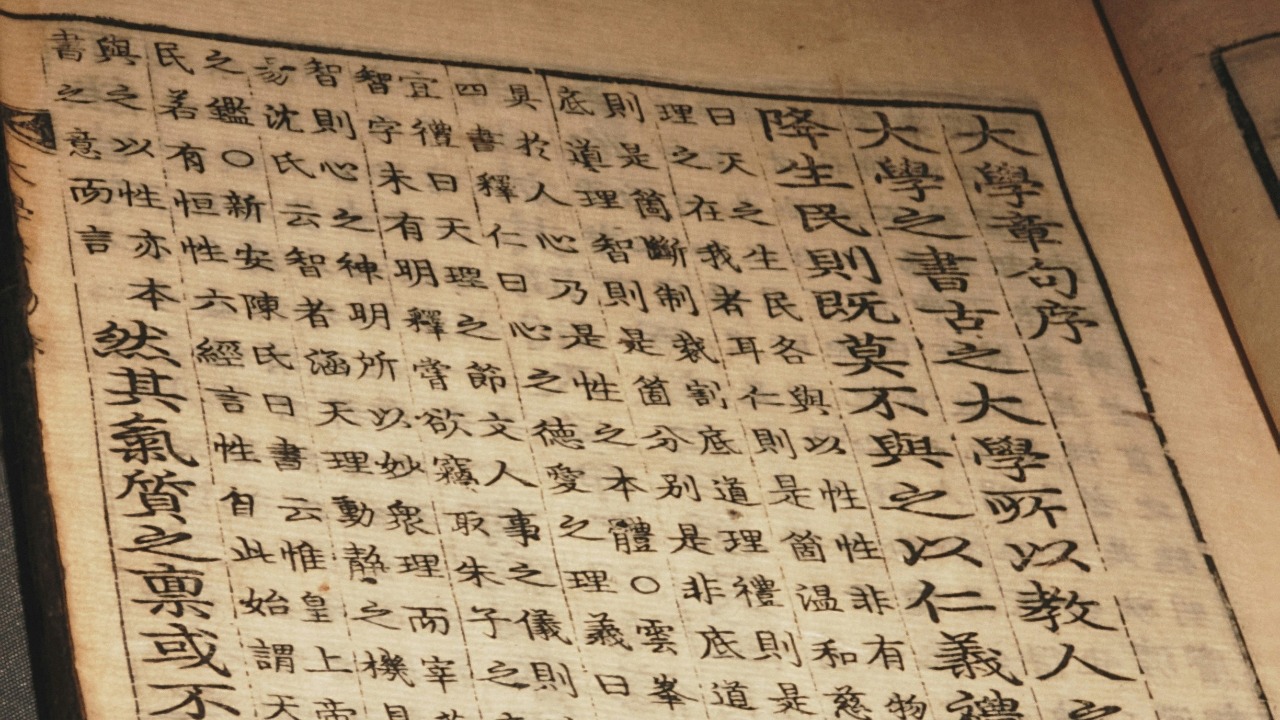

The earliest known Chinese eclipse observations appear in chronicles such as the Bamboo Annals from the 4th century BCE, which list over 30 eclipses with dates tied precisely to royal reigns and ritual events. By anchoring each eclipse to a specific king and regnal year, these records give researchers fixed historical markers that can be compared directly with modern orbital calculations. For historians of science, the stakes are high, because every correctly dated eclipse tightens the timeline of early Chinese history and tests how accurately current models reproduce the sky as it appeared to observers more than two millennia ago.

Texts like the Chou Pei Suan Ching integrated eclipse data with early mathematical models of celestial movements, treating the Sun, Moon, and stars as parts of a calculable system rather than purely omens. When astronomers today align those early numerical schemes with modern ephemerides, they gain a baseline for judging how well ancient predictions matched actual eclipse paths and timings. That comparison matters for planetary science, since any systematic offset between predicted and recorded eclipses can reveal long term changes in Earth’s spin that would otherwise be invisible in the short window of modern measurements.

From Oracle Bones to Rotational Clocks

Among the most striking examples is the annular eclipse of 2137 BCE, noted in oracle bone inscriptions that describe the Sun being “eaten” while diviners recorded the event for the Shang court. When researchers retrocalculate that eclipse, they can pinpoint where the Moon’s shadow should have crossed East Asia and then check whether the ancient description matches a path that passes near Anyang and other early political centers. If the match is close, it strengthens confidence that the inscriptions capture a real astronomical event, which in turn provides a precise data point for how fast Earth was rotating more than 4,000 years ago.

Modern analyses of these inscriptions, combined with later annals, show that the timing of the 2137 BCE eclipse does not line up perfectly with what would be expected if Earth’s rotation had always been constant. The discrepancy, measured in minutes on the ground, translates into subtle but cumulative changes in day length over thousands of years. For geophysicists, that mismatch is not an error to be discarded but a signal that tidal friction, core mantle interactions, and glacial rebound have all contributed to a slowly evolving rotational clock that ancient observers unknowingly documented.

Linking Eclipses to Earth’s Rotation

When scientists compare predicted eclipse times from modern orbital theory with the observed times preserved in Chinese chronicles, they consistently find small offsets that grow larger the further back in history they look. Those discrepancies indicate a gradual slowing of Earth’s rotation due to tidal interactions with the Moon, quantified at about 1.7 milliseconds per century in current models. The practical implication is that a “day” in the distant past was slightly shorter than the 86,400 second standard used in atomic timekeeping, so any attempt to reconstruct ancient events to the minute must account for that drift.

Using Chinese annals as a dense sequence of checkpoints, researchers have modeled historical day length variations and concluded that days were shorter by roughly 50 milliseconds around 700 BCE compared to today. That difference may sound negligible, yet over centuries it accumulates into minutes of shift in local eclipse circumstances, enough to move the path of totality hundreds of kilometers on Earth’s surface. By integrating these Chinese records with Babylonian cuneiform tablets and Greek astronomical reports, teams can build a unified timeline that improves the accuracy of retrocalculated eclipse paths and refines estimates of how Earth’s rotational dynamics have evolved.

Modern Scientific Applications

Contemporary computational models, including those developed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, now incorporate Chinese eclipse data to sharpen long term predictions of Earth orientation and lunar motion. When those models are reconciled with ancient observations, they feed into the parameters that define International Atomic Time and its relationship to Universal Time, which is tied to Earth’s actual rotation. The result is a more precise schedule for leap seconds and related corrections that keep systems such as GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou aligned with the planet’s true spin, a requirement for navigation apps and aircraft avionics that depend on sub meter accuracy.

Refined rotation histories drawn from ancient Chinese texts also matter for climate and geological studies, because they help track how mass has shifted between ice sheets, oceans, and the solid Earth. Changes in day length and polar motion inferred from eclipse discrepancies can be compared with models of ice age cycles and sea level variations, offering an independent check on how quickly ice sheets melted or advanced. As researchers digitize and reanalyze manuscripts highlighted in work such as the study described in recent reporting on ancient Chinese eclipse records and Earth’s rotation, collaborations between astronomers and sinologists are accelerating, giving both fields a richer dataset than either could assemble alone.

Future Implications and Ongoing Debates

One immediate consequence of this research is the prospect of revising historical calendars, including the chronology of Chinese dynasties like the Shang and Zhou, to align more closely with the eclipse record. If a royal accession or major battle is tied to a specific solar eclipse, and that eclipse can be dated astronomically with higher precision, then entire sequences of reign years may shift by a few years relative to traditional timelines. Such adjustments would ripple through archaeology, art history, and comparative studies that rely on synchronizing Chinese events with those in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean.

These possibilities have also sharpened debates over data reliability, particularly when texts show signs of later interpolation or when scribes may have retrofitted eclipse omens to match political narratives. Scholars weigh those concerns against archaeological corroboration from sites like Anyang, where oracle bones and stratified artifacts provide independent anchors for the written record. Looking ahead to upcoming solar eclipses, including the total eclipse of April 8, 2024, educators and outreach teams are drawing on ancient Chinese methods of careful timing and positional recording to explain to the public how each new event adds another point to a rotational dataset that stretches back more than four millennia, linking modern skywatchers to the astronomer scribes who first turned eclipses into a clock for Earth itself.